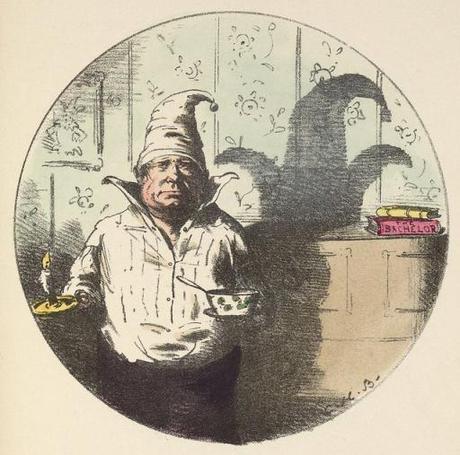

Charles Henry Bennett, A Fool's Cap

Living and working off the coast of the Hudson River as I do, the horizon line is never far away, and it is easy to become obsessed with that narrow, ever-changing band of gray lights where sea dissolves into sky—the screeching of seagulls floating around like a concert of oboes and the basso horns of the deeper barges. I think this is partly why Goodbye, Columbus by Philip Roth, or Ragtime by E. L. Doctorow, resonate so powerfully with me. An arrestingly simple, almost abstract view of Manhattan over this channel at sunset, the marina at the Hudson captures an instant in a landscape at once timeless and organic as well as alien and familiar. Like all of Albert Einstein’s early tinkering with the theory of relativity in Princeton and all the elliptical cracking of the baseball ball at the Yankee Stadium, these thoughts are the result of a moment’s pause on a solitary walk, in this case a circular trek from Jersey City to Hoboken.

Walking is all about a lived experience, and to take part in a walk in the New York marina, as I have been lucky enough to do on a couple of occasions, is to commit to that experience, to see it through to the end despite the vicissitudes of the particular terrain or the weather. The music of Charles Ives encapsulates the spirit of that idea perfectly for me and, though Ives hesitates to quote Romanticism in relation to his scores as directly as in the paintings of Winslow Homer, everything is about the meditative state that walking can induce.

Fulton Street Dock, New York City

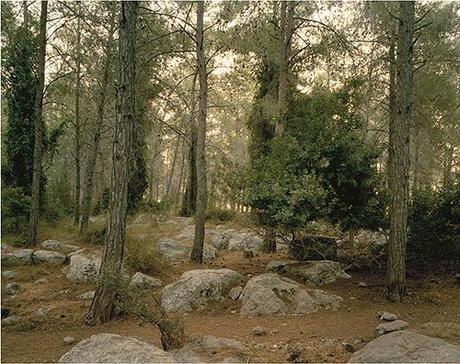

Similarly, an Ethiopian spice market is a space of scent that conveys a powerful experience of the place, both invigorating and voyeuristic. The sound of church bells echoing through the streets of a French town makes us aware of a citizenship that was once won through the sharp blades of the guillotine; the multisensory cracking of branches on the hills of the Apennines also have the extraordinary capacity to reverberate the shots of anti-fascist rifles from the 1940s. (Ultimately, the architecture of the Italian forest is the art of petrified silence.)

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, The Saints Forest, 2005

Even though our ears have been blinded by the sensory deprivation of the modern city, a bundle of parked cars from the roaring 1920s—to return to the U.S.—have not lost their dripping acoustical qualities. They still awaken our awareness of the myopic errands of cream cheese spread over a compendium of bagels, the unpredictability of peppers and grapefruits on the moving stands, the sobbing of girls at the motion pictures, the creases of flannel pants leaking down like an accordion. . . The dim origins of football and baseball come and go, like the fairy-tale crouch of Geppetto ready to burst into “La donna è mobile.”

April 26, 1923, Washington D.C.

Every month or two, history tests soccer’s capacity to generate power—or watts—and, like Lance Armstrong routinely tinkering with carbon titanium and riding near a red barn in Texas in preparation for the season, the impending fixtures suggest to test the so-called “beautiful game” in the same way one might try to get a better sense of what statistical and tactical measures really meant.

And so it was this week—weeping on the stage, weeping in all the rows. Mourinho, more than many others, embodies that old, feverish drama of the fetishistic sport devotee. If he was a New Yorker, the Portuguese’s heat would smell of rusted radiators in the Lower East Side; the body, down on his knees during the penalties against Bayern Munich, became a cavity sculpted by history directly in the interior of the mind, like the cylindrical, underground tunnels of Vienna in Orson Welles’s film The Third Man. Guardiola, by contrast, cultivates worshiped nuances: he delivers, of course, but through shadow, intimation, instinct. As a New Yorker (an old-timer, Yiddish actor snatched from the velvet boudoir of Europe), he would naturally belong to one of those known-to-be-extinct five-story tenements of the Bronx in the 1930s—an obsolete yet amazed proscenium, as when the Quakers concentrate on a whiff of summer ozone to receive the Light of inwardness or when the director is determined to carve shapes out of the wobbly floorboards of the theater.

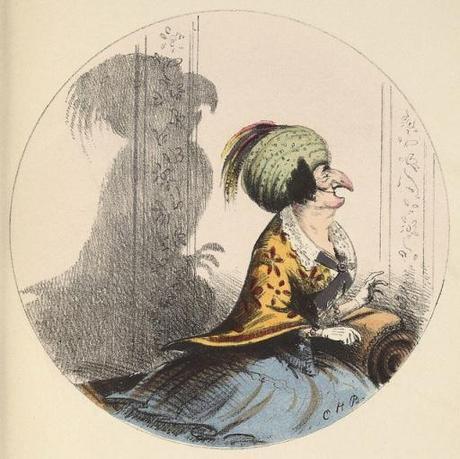

Charles Henry Bennett, A Parrott

Dying, dead, finished. . . Where is the caricature, the exaggeration? Where’s the overture, or who’s going to play Lear and Falstaff, for God’s sake? I’m talking heat, muscle, human anguish. Where is the theatrical noise in the sporting life today? Perhaps it is all in the hands: a complicated organism, “a delta in which life from the most distant sources flows together surging into the great current of action,” as Rainer Maria Rilke wrote in his essay on Auguste Rodin.

As Heidegger suggests, the hand carries itself through the element of thinking; the skin of a dribbler, for example, reads the texture, weight, density, and temperature of the ball he handles, whether in football or basketball. Unlike the tennis ball, which passes too quickly for the spectator’s eye, the dribbler has developed skills that are perfectly suitable for the backcourt. A star is often a point-hungry gunner, like Kobe Bryant, or a greedy hunter of episodes, like the late Alessandro Del Piero, but a dribbler restrains from the style of playing that might be condensed to “When in doubt, shoot.”

He is the center of a team because of his ability to shag rebounds. He can play in any terrain; he is the master of all the gestures of big men, but has the moving skills of the little men too. His education is made of playmaking and defense, not glamorous contributions but teammating. A dribbler is the result of high percentage of accuracy, and he would only attempt a pass through the eye of a needle if that means he’s feeding the ball near the basket or at the edge of the play.

The sureness of the coaching American man, on the other hand—black or white, greenhorn novice or craggy veteran, the perennial gum on his fat lips, the whole thick torso glowing under a navy blazer, a gold high-school ring on his right pinky finger, and the hair as scruffy as those of somebody who knows how to make things happen—comes straight from showbiz. And yet all of this seems childish by now, the script of somebody freshly deceased. Presumably, though, there is something of the Hollywood agent and the stock exchange broker (a business card folded in his brown Fedora) in Italian football coaches such as Roberto Donadoni, prickly and oddly jaded as a vexatious neighbor, or the unimpeachable Giampiero Ventura, with brass buttons and raised-collar T-shirts, who looks exactly like what a night of rye and Lucky Strikes would do to you.

Fernand Khnopff, An Abandoned City, 1904

In the first night of the Chernobyl disaster—a shock, a great vibrating danger, a shifting amoeba without a nucleus—I was practicing my tennis on the courts of the Pro Patria club in Milan. I was twelve, and I had yet to know a woman. It was before the city turned into frenzy and paranoia, with people drilling shelters and cubicles in the basement, and stocking carts of fresh milk in the fridge. (Within a few hours, the traffic stopped entirely, as in the abandoned city of Fernand Khnopff, a disfigured Belgian picture, crossed out from humanity as though for avenging the country’s horrible colonial crimes.) And suddenly I took in drizzles of a poisonous, red rain dangling from the neck after the last top-spin. There was fear in each lone laugh. Everyone who took shelter in the locker-room had a horrifying head, resembling what I remembered of Job—diseased, cut down, humiliated. We all wished we could live another hundred years. The Russian doom was a word-collector, a pad of whispers carried in its pocketbook.

Yet, the radioactive invasion already tapping in the back of one’s throat, there was somebody who had survived the sweating and the risks. It was a famous member of the Pro Patria club, Alberto Cova, who was by then the gold medalist in the 10,000m at the Olympic Games in Los Angeles: the superfluous, tiny body of a mustachioed shoemaker, protected and isolated from the outside as the tapestries of a secret chamber. He kept running on the race track under the strictures of the red drizzle, as if rocked by the unfamiliar theatricality. All that kept the audience worried since the radio announcement—the loudness, the broadness, the brazeness, the bigness—would probably seem something farcical to him. Cova had already chosen his role, like a character-actor. He would relish a slow-paced beginning, spotting the reviewers and eavesdropping on the murmurs, the sighs; at this stage, being inside the pack would feel a lot like standing at the center of a cycling peloton, moving along in orderly fountain-pen prints. But an inch before the final lap, the judge’s bell boldly resonating as in adaptation of an ancient Greek play, Cova would sprint (and win) in transgression, in rapid pencil strokes.

Cova was a minimalist. He repudiated the gaudy postmodern experimentalism, the tricks of the trade, all the anecdotes and rumors of the Olympic village. When finally he was defeated, a couple of years later, it was fruition, it was anticipation at his own game: not the silly, nervous buffoonery of the media. Naturally, Cova wouldn’t put in an appearance. He did not do it for the paycheck, nor for glory. His way of running was that of a poor, bare, forked animal, or, perhaps, that of the Kenyans training in the gutters of a city street, spitting out forgotten exiles and the old lost kingdom of Alexandria. Against Chernobyl’s wasted eggs and empty uterus, Cova’s run on the track was the wild roaring cannon of a human heartbeat.

For days after the nuclear blast, Milan smelled of flour. The cooing birds would be found with the one blue eye, the one dead eye. The sporting life was still businesslike; showing up being nine-tenths of talent. Soccer at San Siro, in particular, was the concerned effort of a theater’s director. Everything turned up because of the thunderclap—tactics were not a straitjacket for any actor, and there was space for the toughtful and intricate passing of a midfielder, or the raw vertical runs of a winger. (It was in this tentative psychology of the game that Guardiola forged his monologues, scouting scenarios for the geezer and wandering off, out of consummated professionalism, with a beard and a tattered Franciscan sackcloth.) Feather on feather, at that Yale school of drama that is AC Milan, Fabio Capello and Arrigo Sacchi were both in apprenticeship. One would have presumably considered Chernobyl as a fastidious event, a distraction in the flow of his massive, self-assured European cartography; but the other would have used even the nuclear cloud to charge you up. You always had the sensation, with Sacchi, of an electric wire going up your spine, probing and poking your vertebrae. For, as a matter of fact, Ives and the marina at Hoboken, or the Pro Patria athlets, were right about actors doing sports. If Guardiola is monkish, Mourinho is an enthusiast; Capello and Alex Ferguson, as theater directors, know their craft as an abrupt ascent into authority and reputation, while others stick to their role, scruffy and spacious, all because of the buzz. ♦