Leopards are the most elusive species of the big 5. They can draw in tourists over thousands of miles, who are willing to pay top dollar for the opportunity to see and to photograph leopards in their natural habitat, either in national parks or on private wildlife reserves. National parks alone are insufficient to protect leopards in the long term, and the survival of leopards on private and communally owned land is critical to their long term viability. But on private and communal land leopards often come into conflict with people. Leopards are said to be the most persecuted cat in Africa, and this has taken its toll on the leopard population. Leopards have already disappeared from 37% of their historic range in Africa. There are vast tracks of land in South Africa where leopards used to live, but are now locally extinct. People are encroaching on the last remaining leopard habitats, leaving their livestock roaming freely in the bush without protection, and pulling out their rifle or putting out poison when a leopard fails to pass up on a free meal.

Carcass of a collared leopard named Pimms, who was killed by a snare in June 2015

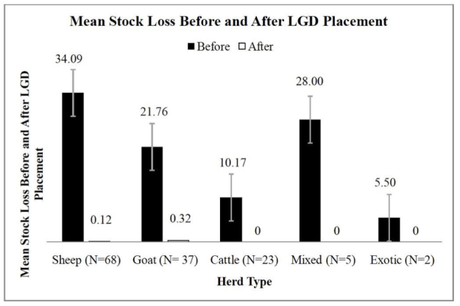

The effectiveness of livestock guarding dogs at reducing predation (Leijenaar et al., 2015).

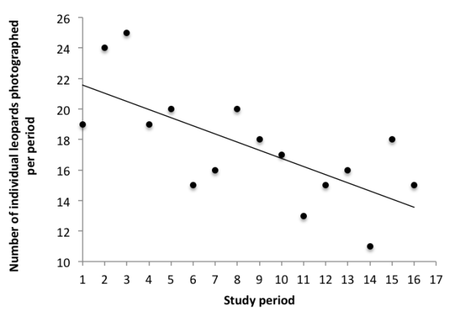

Livestock guarding dog hard at work protecting his herd. Number of individual leopards photographed on our static camera trap array in the Soutpansberg Mountains.

Camera trap image showing BB snarling at Rowena Leopards used to roam throughout all of South Africa, but they are now absent from most of the country.

Are things any different here in the Soutpansberg mountains? The Primate and Predator Project set out to find out - we have been using camera traps to study trends in leopard abundance over the past 4 years. We are currently crunching the numbers to see how local leopard density has changed over the years, but preliminary results suggest that the number of individual leopards photographed has steadily declined month after month. But what the cameras can't tell us what the fate is of the leopards that disappear.

To answer this question we fitted GPS collars to eight leopards, and each leopard wore the collar for 15 months. By the end of the study period, only 2 leopards were left alive, and one of those would have been deliberately poisoned if it was not for intervention from the PPP. The rest were either shot, snared or went missing, presumed dead. They were not migrating, not dying from disease or fighting with each other, nor were they peacefully expiring of old age in their sleep after a long and prosperous lifetime. They were being killed by people.

So who was killing the leopards, and why? The main driver appeared to be the perceived risk of livestock predation. The farmers we spoke to were worried that leopards would kill their calves. Our studies show that in this area leopards eat almost exclusively wild animals, but we know that leopards do occasionally feed on livestock, and this is one of the major reasons why people kill them.

So what can we do to turn things around? There are lots of things that can be done to reduce livestock predation: keep small stock and calves in strong livestock camps at night; locate camps far from predator habitat and near to human habitation; herd livestock. But studies have shown that using a livestock guarding animal can also be extremely effective at reducing livestock predation. We want to buy a livestock guarding dog, place it with livestock in the Soutpansberg area, and support the dog and the farmer to protect the herd. This way the livestock will be safe, and the farmer won't have to kill any more leopards.

This weekend I will be running the Skukuza Half Marathon inside Kruger National Park to raise money to sponsor a livestock guarding dog. This is where you come in. If you are willing to help out by donating money to help leopards and people to coexist then please click here.

Thank you.

Sam Williams

Research Coordinator, Primate and Predator Project