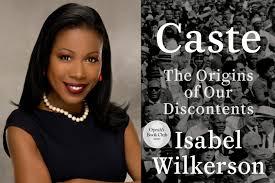

Isabel Wilkerson’s book The Warmth of Other Suns, about Blacks leaving the Jim Crow South, was inspiring. Her new book Caste is dispiriting.

Wilkerson defines caste as a cognitive system situating people in a social hierarchy, governing who’s on top and what others are deemed allowed to do. Captured in that old locution about Blacks “knowing their place.” She brackets America with the caste systems of India and Nazi Germany. Seeing this as the skeleton underlying America’s social architecture, analogized to the unseen programming imprisoning people in The Matrix, with only rare individuals able to realize it and free themselves.

So this isn’t just about race and racism. Nor does the word “class” cover it, referring to economic differences. Caste is a broader concept, concerning social status relationships. The ability of even the most degraded Whites to hold themselves above Blacks has been a crucial fact of American culture. Taking it away feels devastating to many, relegating them to the bottom.

Wilkerson posits “Eight Pillars” for a caste system:

1) Divine sanction. Blacks supposedly descended from Ham, one of Noah’s three sons, cursed by him (unjustly).

2) Heritability — people born unchangeably into their caste.

3) Regulating procreation to preserve caste boundaries.

4) A concept of purity versus pollution. Thus the “one drop of blood” rule concerning ancestry. I recalled Faulkner’s novel Absalom, Absalom! — where a plantation owner rejects his daughter’s suitor — not because he was already married — nor even the relationship being incestuous. The real reason: one drop.

5) Occupational segregation, exemplified in India, where caste dictates one’s work.

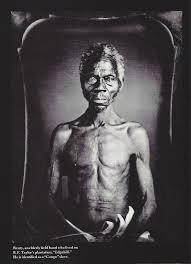

6) Dehumanization and stigma. Wilkerson details how Nazis and America’s slave system stripped victims of perceived humanity.

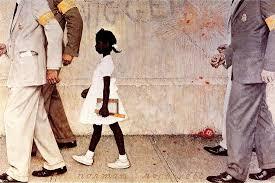

7) Terror as enforcement and control. To keep slaves in check, they were brutalized, even though this meant masters damaging their own property. Emancipation removed even that inhibiting factor. Thus lynchings.

8) Concepts of inherent superiority and inferiority. Each caste supposedly deserving its status.

Wilkerson gives a harrowing account of slavery’s U.S. history. While slavery has existed since civilization’s beginnings, in most cases victims bore no physical markers for their status. Thus it was subject to erasure. Even India’s rigid caste system is short on overt physical cues. But in America the visual distinctiveness of Blacks served to exacerbate their perceived low status and perpetuate it across generations.

In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2013 novel Americanah, the Nigerian protagonist says she never knew she was Black until she came to America. Wilkerson quotes a similar statement, likewise saying no European is “White” before coming here. She makes the familiar argument that these racial categories are not actually biological facts but social constructs. Human DNA is 99.9% identical. The supposed division into three “races” was always junk science, struggling to justify some sort of hierarchy among people based on immaterial variations. It’s nonsense to deem any human subgroup innately superior or inferior. And in any case “racial” characteristics are not distinct but blend into each other in a continuum of gradations. Some “Whites” are darker than some “Blacks.”

Yet these points seem at odds with Wilkerson’s argument about clear visual markers facilitating U.S. caste divisions. Those differences of skin color and other physical attributes are real enough. We know what we mean when saying someone is Black. And that, Wilkerson writes, is “the historic flash card to the public of how [Blacks] are to be treated, where they are expected to live, what kinds of position they are expected to hold,” and so forth.

She relates some humiliating personal experiences. In one, as a New York Times reporter, she went to a scheduled interview, and the guy wouldn’t accept who she was. Saying, “I must ask you to leave, I’m awaiting an important interview with the New York Times.”Reading of Wilkerson’s air travel indignities reaffirmed my eschewing First Class and its entitled jerks — but also reminded me of my white privilege. I’ve hated that term; believing it’s just normality; that the issue is really Black dis-privilege. But the book made me think about my running in airports and other public places — very risky if I weren’t white.

There is a large political dimension to all this. Wilkerson describes a film of Germans adulating Hitler. She says the Nazis needed masses falling under the spell, susceptible to propaganda giving them an identity to believe in. Seeing the same dynamic in Jim Crow’s brutalities, reflecting the “weaknesses of the human immune system.” Not speaking biologically, of course. She quotes psychologist Erich Fromm regarding one aspect of dominant caste mentality: “He is nothing, but if he can identify with his nation, or can transfer his personal narcissism to the nation, then he is everything.” And social theorist Takamichi Sakurai: “Group narcissism leads people to fascism . . . a fanatical fascist politics, and extreme racialism.” Fromm too pointed to Nazi Germany and (writing in 1964) the U.S. South. With the working class particularly susceptible — “eager to have a leader with whom it can identify.” And “the narcissism of the leader who is convinced of his greatness, and who has no doubts, is precisely what attracts the narcissism of those who submit to him.” Does this ring a bell?

Many of us imagined Obama’s election signified America finally graduating to post-racial nirvana. But the book discusses how it freaked out many Whites and actually triggered retrogression. Not just a backlash by bitter-enders, but a general heightening of White caste truculence. Before, dominance loss seemed hypothetical and distant. Now it felt real and present. Made worse by Obama being so obviously a superior person, confounding negative stereotypes about Blacks. The old hierarchy (in which Whites knew their place) seemingly turned upside down. Antipathy toward Blacks increased.

While liberals have long bemoaned working class people voting against their economic interests, many actually see their interests differently — putting caste status above other concerns. Viewing undeserving groups as getting ahead at their expense. And Republicans as representing White caste interests, while Democrats represent the groups threatening them.

Republicanism also reflects evangelicals’ abortion obsession. But that always seemed excessive. Now I wonder whether it’s a kind of displacement for something deeper: racial caste anxiety. I come back to Jonathan Haidt’s metaphor (in The Righteous Mind) of the rider and elephant, representing the conscious and unconscious minds. The rider thinks they’re directing the elephant, but it’s really the other way around. Riders may believe they’re battling abortion — but are their subconscious elephants ruled by caste insecurity?

And Wilkerson says that while most White Americans disavow or even ostensibly oppose racism, so pervasive is Blacks’ stigmatization that 70-80% hold unconscious biases affecting their behavior without their even realizing it. She also thinks this lies behind America’s social ethos being harsher than in other advanced countries where people are more caring toward each other. Whom they see as fellow citizens, like themselves. America has, rather than such social solidarity, a deep resentment by the White dominant caste toward nonwhite others. Thus all the hostility toward social programs, again seen as unduly benefiting those (undeserving) others.

Wilkerson quotes historian Taylor Branch: given a choice between democracy and Whiteness, how many would choose the latter? And she similarly queries whether the U.S. will adhere to the principle of majority rule if the majority looks different. Some at least gave us an answer on January 6 when White supremacists carrying Confederate flags invaded the U.S. Capitol — something they never accomplished in 1863. Their caste defensiveness translating into nihilistic, anti-democratic, anti-rationalist Trumpism.

Wilkerson notes that Germany has no Nazi memorials, they’re ashamed about that history. There are neo-Nazis in America but not Germany. They have memorials to victims, and even pay compensation to them. My mother still gets a monthly check, having escaped the Nazis. But in my childhood, Jews’ own past history as a despised caste engendered no sense of solidarity with Black Americans. They were indeed considered below us in exactly the way Wilkerson describes.

Yet I believe most Americans have now progressed beyond that. Wilkerson’s interview anecdote seemed more bizarre than typical. That guy shamed himself, not her. Only a fool today would be thrown off by seeing a Black in any prestigious role.

Black Americans do still suffer from persistent after-effects of past subordination. America spent almost twice as long with slavery than without, and the societal impacts don’t disappear easily. Particularly fraught are Blacks’ interactions with police and the criminal justice system. But whereas in the past, such disparate treatment was accepted as normal, that is no longer true, with widespread public understanding that it’s wrong and needs fixing.

At one point Wilkerson refers to a coddling of Whites’ self-images “from cereal commercials to sitcoms.” Perhaps she doesn’t watch enough mainstream TV to realize that ads nowadays actually disproportionately feature Blacks. But many Whites have noticed. My 2017 blog post about this got more hits than any other, and way more comments — the vast majority expressing crude racist hatred. But they’re surely no representative sample of American sentiment.

When I see a Black person, I do see a likely descendant of slaves — but as part of recognizing something opposite to Wilkerson’s theme — the remarkable degree to which such people are normalized — integrated — in today’s culture. Increasingly, I see them as the very backbone of America, in job after job, the working folks who make our society function.

A recent David Brooks column observed that “racial sensitivity training” never seems to actually change people’s attitudes. What does, he said, is putting them in extended relationships with different people. They adapt to the new circumstances, developing new conceptions of who is “us” and who is “them.”

Wilkerson writes of a plumber arriving at her house in a MAGA hat. At first he was cold and unhelpful. But then both spoke of recently losing mothers. That human connection overrode the caste hostility. We have similarly seen examples where antipathy toward immigrants melts when people actually interact with them.

White supremacy is a lie, and people believing it prove who’s really inferior. While Blacks who, despite all the crap they have to endure, are decent human beings, prove they’re the superior ones. As activist Kimberly Jones said, Whites are lucky Blacks want only equality — not revenge.

Racial conflict is not inevitable. After the Civil War, with Blacks only just emerged from the most degrading, despised condition, and few Whites truly believing them equal, America nevertheless made them voting citizens. That humanistic generosity of spirit still takes my breath away.

Strangely, Wilkerson says virtually nothing about what I see as the true caste divide in today’s America — not between races but educational levels. Blacks who get well educated basically join the upper caste. That’s not to say they never experience painful slights like those Wilkerson relates. But those are not (or needn’t be) central to their overall life experience.

It is true that race and educational attainment do correlate to an unfortunate degree. This is the biggest continuing after-effect of America’s racialized history. We cannot erase skin color but we can— if we really set our minds to it — ensure equal educational opportunities. It’s long overdue and would solve most of the problem we all live with.