Headquarters of the South African Development Community in Gaborone, Botswana. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Much of the discussion at last year’s landmark U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit in Washington, DC, focused on transatlantic trade and investment between the U.S. and African countries – for example, the need to renew the African Growth and Opportunity Act, which aims to promote trade with the U.S. by removing tariffs on a number of African exports. Another theme that was prevalent throughout the summit, however, was the need to open up borders, reduce barriers, and increase trade between African nations.

It’s becoming quite common to talk about the rise of Africa and the potential return on investment in a continent often compared, demographically and economically, to countries like China and India. In fact, even developing sub-Saharan Africa is slightly richer than India on a per capita basis, and the continent as a whole has a larger GDP. The economic potential of Africa’s billion people, as both workers and consumers, is only beginning to be tapped.

These statistics are accurate and encouraging, but they can also be slightly misleading. Africa is not a single country, like China or India. It is 54 different countries with 54 different sets of borders and laws creating 54 fragmented, often tiny markets. Doing business in China or India means over a billion people as potential customers or employees. But there is no equivalent “African market.” Investing in Cameroon does not give you much access to Algeria or Zimbabwe, or any country in between. High tariffs, bureaucratic red tape at the borders, and poor infrastructure all make it hard for goods, capital, and workers to move freely through the continent.

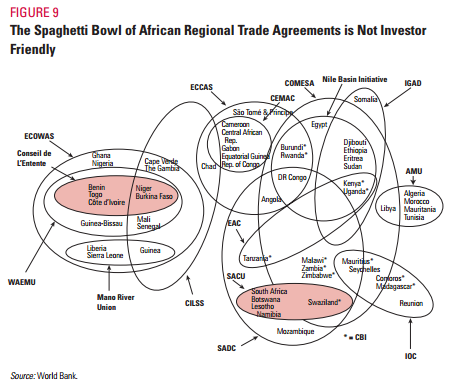

Undeniable progress has been made in regards to tariffs, with the establishment of regional trade blocs such as the Southern African Development Community (SADC), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and the East African Community (EAC). Yet there is still much that needs to be done to unite the continent and also to integrate it with the rest of the world.

Disconnected Neighbors

The large majority of African trade is with Europe, North America, and China — not with neighboring countries. An oft-quoted statistic is that it costs $1,500 to ship a car from Japan to Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, but shipping the same car from Abidjan to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, costs $5,000. According to research by Ecobank, only 12 percent of Africa’s trade stays within the continent. And this includes the trade originating from Africa’s 16 landlocked countries that must pass through neighboring countries before arriving at an overseas destination.

Increased integration would benefit all African nations – particularly smaller economies and those 16 landlocked countries, which are among the poorest in the world. Barriers to regional trade most heavily affect the poor and women, who would have a comparative advantage of “catering for smaller, local markets across the border” in a more open system, according to a a 2012 World Bank study. Meanwhile, an Asian Development Bank report found that integrated markets are particularly valuable for small economies, which benefit from access to larger export markets and larger pools of human resources and capital.

Regional trading blocs were supposed to be the solution to these problems. But Africa currently has 14 different, often overlapping economic blocs, which have mostly proved disappointing. As an example, the Democratic Republic of Congo is a member of four different regional economic communities, but has only ratified two of the 56 protocols and amendments for the SADC – essentially making its SADC membership futile.

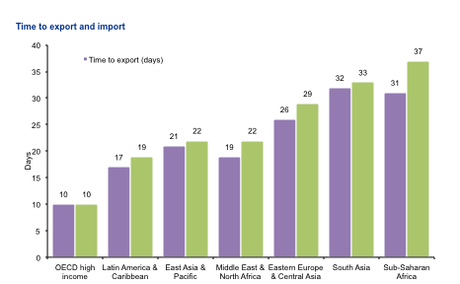

Despite the energy and resources put into forming these blocs, Africa still remains woefully behind in easing burdens on trade. The average time to import within Latin America is 22 days. It’s 12 days within the European Union. The average time to import within SADC and COMESA, however, is 38 days. “Clearly,” says Karen Hasse of Good Governance Africa, “trade in Africa is overregulated.”

via KPMG Africa, 2013

In June, African leaders took a step towards greater economic integration by signing the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) deal. If ratified, it would unite half the continent, from Cape Town to Cairo, directly affecting 625 million people. The TFTA would integrate three existing trade blocs — the East African Community, the Southern African Development Community and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), representing more than $1 trillion of GDP.

But simply reducing tariffs will not be enough to kickstart intra-African trade. Check back on the CIPE Development Blog tomorrow for the second part of this article, which discusses the critical role of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) — and what can be done about them.

Ryan Musser is Program Assistant for Africa at CIPE.