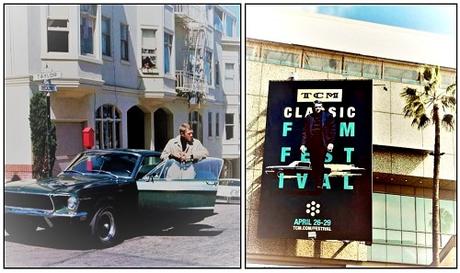

The TCL Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, famously known for decades as Grauman’s, is the most historic of movie palaces world-wide, and one of the most magnificent. Famed for its lavish “Oriental” décor, its klieg light-lit Old Hollywood movie premieres, and its hand- and footprint-studded forecourt, the theater has been a shrine to cinema since 1927, when it first opened its doors. An IMAX theater since 2013, it continues to be the foremost Hollywood venue for major movie premieres. The theater is also the scene of showcase screenings during TCM’s annual classic film festival in Hollywood.

On last April 28, a Saturday, every one of the Chinese Theatre’s 900+ seats were filled for a 50th anniversary tribute screening of Bullitt (1968), Steve McQueen’s trailblazing signature film. This TCM fest screening may have been first of the many 50thanniversary nods to the New Hollywood classic that cropped up around the country at smaller indie theaters during the year. This month, on Oct. 7 and 9, Fathom Events celebrates Bullitt’s 50thwith big screen presentations in theaters across the US. Click herefor details.

On last April 28, a Saturday, every one of the Chinese Theatre’s 900+ seats were filled for a 50th anniversary tribute screening of Bullitt (1968), Steve McQueen’s trailblazing signature film. This TCM fest screening may have been first of the many 50thanniversary nods to the New Hollywood classic that cropped up around the country at smaller indie theaters during the year. This month, on Oct. 7 and 9, Fathom Events celebrates Bullitt’s 50thwith big screen presentations in theaters across the US. Click herefor details.

The Thomas Crown Affair (1968)

Bullitt is the film that cemented Steve McQueen’s lasting superstardom. He was already an established A-list movie star in 1968 and had, at the time of Bullitt’s release, scored a major hit four months earlier with a stylish and entertaining spectacle of split-screen photography, The Thomas Crown Affair. Thomas Crown had been an intentional departure for McQueen, who was uncredited producer on the film. The Crown character, in contrast with McQueen’s typical role, was an impeccably tasteful, free-spending Boston-based millionaire, if also a larcenous iconoclast. In Bullitt the actor returned to type or, more precisely, mined the very essence of his onscreen persona and came up with gold. The film was a smash and a trend-setter, and it established forever McQueen’s reputation as the coolest star of the coolest decade. McQueen, whose company, Solar Productions, produced Bullitt, chose British filmmaker Peter Yates to direct. He had seen Yates’s Robbery (1967), a film that impressed him with its dramatic car chase scene. McQueen loved cars and Yates had worked for HW Motors (Aston Martin), a company with a racing team headed by Stirling Moss. Yates was also experienced with location shooting, having worked with Tony Richardson (The Entertainer, Tom Jones) who always shot on location. This was another advantage for the director, since McQueen intended that Bullitt be filmed on location and, at that time, the majority of Hollywood directors were lacking in on-location experience.

Steve McQueen and Peter Yates on the set

Originally, L.A. was considered, but San Francisco was ultimately chosen for the location shoot. The reasons went beyond the photogenic superiority of the city to the north. For one thing the director and production company would have a freer hand in San Francisco. For another, L.A. was thought to be overexposed, thanks to TV and the glut of police series set there. As it turned out, Bullitt launched what San Francisco Chronicle culture critic Peter Hartaub has called the “Golden Age of San Francisco Movies,” from 1968 – 1974, when films including Dirty Harry (1971), What’s Up, Doc? (1972) and The Conversation (1974) were shot in the city.Bullitt launched more than that. The film’s centerpiece car chase sequence would ultimately influence every one that has ever come since, including William Friedkin’s The French Connection in 1971, winner of five Oscars including Best Picture. Bullitt’s 10-minute chase segment has long been acknowledged asthe “granddaddy” ofall movie car chases.The chase is on (via Giphy)

The success and acceptance of McQueen’s maverick cop archetype in an “anti-establishment” era also paved the way for those that followed. Most notably, Clint Eastwood’s renegade cop, Dirty Harry, enjoyed a five-picture, 17-year run (1971 – 1988). In fact, McQueen, not wanting to risk repeating himself, had turned down the lead roles for both The French Connection and Dirty Harry.Bullitt has even been cited as the first “action movie.” Tom Breihan of A History of Violence (https://film.avclub.com), whose column annually picks the “Most Important Action Movie of the Year,” posted a piece a couple of years ago that declared, Action cinema begins with Steve McQueen and one incredible car chase. While Breihan gives a respectful nod to “other genres…that supplied the kinds of thrills that action movies would later provide” as well as to proto-action movies, he believes that Bullitt brought with it “the moment when a hard-edged, unflinching, modern action movie—one built as much around its set pieces as its characters—found mass acceptance.”

The look: jacket, turtleneck, desert boots

And while we’re examining influence, we can’t overlook Bullitt’s impact on men’s style. Theodora Van Runkle, costume designer on the film, had first worked with McQueen on The Thomas Crown Affair. For Bullittshe radically adjusted her approach, adapting McQueen’s own look in combination with that of her then-boyfriend: dark blue turtlenecks, tweed jackets, trench coats and desert books. According to Peter Yates, most of this wardrobe came from Dougie Heywood in London, a favorite of McQueen’s. This lookwould become iconic and inspire men around the globe for decades. Even now, it still does.~So, how does Bullitthold up 50 years on? To begin with, there’s no denying that Steve McQueen at his peak is a potent presence. There’s a scene in Bullitt's apartment in which he’s getting ready to leave and he quickly, very casually, brushes his hair. With one hand. It’s a momentary bit of business that speaks volumes about his appeal and tells us something about Frank Bullitt, too. Director Peter Yates said of Bullitt that the plot, the convoluted escape from custody and search for a mob witness, is actually the minor story, “it’s about McQueen’s character,” he said. Bullitt’s character is established in ways both subtle and bold from the film’s first scenes. At his neighborhood market he roams the aisles, stops at the freezer section and randomly piles frozen dinners into his shopping basket; he nonchalantly steals a newspaper from a corner vending machine; he rides in the back of an ambulance to watch over and comfort a wounded officer; he takes his girlfriend (Jacqueline Bisset) to a trendy restaurant where jazz plays in the background; he commiserates with a black doctor who’s been slighted by a powerful white politician; he won’t back down even a notch when pressed by that same politician; he doggedly hunts down the mob fugitive.

Steve McQueen as Frank Bullitt, Nob Hill, San Francisco

Dialogue is spare in Bullitt. According to Yates, McQueen didn’t like dialog and considered himself “a reactor, not an actor.” He conveys Bullitt’s character communicating through his eyes, posture, movement and gesture, and through his tone of voice. McQueen’s minimalist approach is low-key and casual-seeming. Watching him today, he is as contemporary as he was 50 years ago.Scores of action films have come and gone since Bullitt dazzled movie-goers in 1968, but the “granddaddy” has aged well. William A. Fraker’s no longer unfamiliar cinema verité style of cinematography still delivers the necessary sense of immediacy, of being right there amid the noise and sweat and intensity of the action. Lalo Schifrin’s pulsing jazz score, while clearly of its time, is in complete harmony with the look and the pace of the film. Schifrin, probably best known for his Mission Impossible theme, would go on to score the Dirty Harry movies.The groundbreaking films from the early years of the New Hollywood era were often heavily nominated but under-awarded by the members of the Academy (see The Graduate and Bonnie and Clyde). Bullitt was nominated for two Oscars, and Frank P. Keller took home the statue for Best Film Editing. Keller’s master class of a car chase sequence could not be denied.