Superintendents in the South Bronx had one tough job. In addition to overseeing the grounds, doing the maintenance and repair work, and striving to keep their cantankerous tenants in line and up-to-date with their rent, most New York City superintendents also took responsibility for their buildings' security.

In fact, many of the superintendents, called "the super" by a majority of the residents, considered themselves to be the first line of any building's defense. But there were always those who took their tasks as makeshift policemen a trifle too seriously, while others could not have given a day's worth of crap if their buildings went to pot.

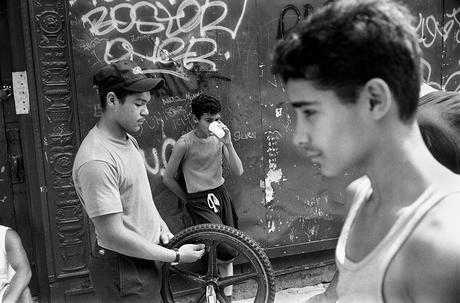

If some of the local troublemakers weren't adding graffiti to their building's outer walls, they were creating a nuisance by playing loud music at all hours of the day and night, and generally making the other tenants and neighbors resemble pawns in the nonstop turf wars that soon enveloped the South Bronx and other areas of blight in the city that never sleeps.

Taking out the trash, keeping vandals away and at bay from renters' homes, changing burned out light bulbs, getting the elevators to run properly and efficiently on any given day, seeing to the upkeep of laundry facilities, and, worst of all, trying to control the ever-growing pest population - rats and roaches, as well as rival gangs, among the worst offenders - these were fulltime jobs for most "supers," be they good or bad.

Speaking of which, the superintendent of 1245 and 1255 Stratford Avenues happened to be a dark-skinned, dark-haired native Puerto Rican from Guaynabo named Benjamin Cardona, whom everyone called "Benny" for short. By this description, anyone who looked at Benny at first glance might have pegged him for a Mexican descendant. The young people, Sonny and Juanito among them, never called him by his real name. He and others like him were invariably referred to as "The Super." If only they had lived up to their moniker! Things would have been a whole lot better, and life a whole lot easier for residents, had that been the case. That's not to say that Benjamin Cardona, or Benny, or The Super, wasn't up to the task.

As with most such immigrant laborers, Benjamin Emanuel Cardona Lopez was a decent fellow, a hardworking individual in his late thirties (or maybe early forties - it was hard to tell by his looks alone), with several kids of his own to care for and a diligent working-class spouse who Sonny rarely got to see, and whose name he never got to know. "Mrs. Super"? That was as far as Sonny got with that.

If Benjamin Emanuel Cardona Lopez had his faults, it was that he gave people who didn't know him personally the appearance of always being irritated with something or someone. He couldn't help the fact that his thick, difficult-to-comb hair was jet-black in color; that he had a five o'clock shadow at 11:00 a.m. in the morning; that his darkly tanned facial features and heavily lined brow, chin, and forehead gave Benjamin the look of a reconstituted caveman come to life. What nature provided him in sour looks and disposition did not, by any means, extend to his height: he barely clocked in at a heavy-set, five-feet and seven-inches.

"Dang, he's one tough looking dude," Sonny mumbled to himself upon seeing the busy super leave his basement apartment. "He could've been a superhero, right Juanito?"

Juanito nodded. "Yeah. Superhero. This must be his day job!"

"Right on," Sonny replied, giggling to himself. Even in his work clothes, Sonny gathered, the super gave off nothing but bad vibes. "He's no Clark Kent."

"You got that right," Juanito chimed in. "That guy Kent was mild-mannered, and he worked for a newspaper."

"Hah, yeah. But this guy... Man, I don't think he can even write! What a joke!"

To both of the brothers, the dark-complexioned superintendent resembled a surly, no-nonsense, sour-tempered tough who took no crap from anybody and lacked a relatable sense of humor. Sonny pictured the super Benjamin as the incarnation of a Western villain, or maybe a Mexican bandit, the kind who sports a big black hat with thin black mustache, riding into town looking for trouble.

"You know who he reminds of?" Sonny said to his brother. "He's like that fake Mexican bad guy played by Humphrey Bogart, you remember the guy... Uh, Morell, I think his name was. In that movie with Errol Flynn..."

"Yeah, Virginia City," Juanito quickly answered.

"That's it! Virginia City! Hah!"

Not one of Bogart's better screen assumptions, Morell was a mix of half-breeds. Half Mexican, half American, part mangy mongrel, all phony baloney. And with a fake Mexican accent and that little black mustache to top it off, not to mention old Bogart's growling, rabid-dog vocal mannerisms. An uproariously and obviously fake movie portrayal, completely over-the-top and patently stereotypical.

"You think he's Mexican?" Juanito asked, turning to Sonny.

"Who, Bogart?"

"No, the super."

"Nah, he's Puerto Rican. Like us. Papi told me so."

"When did he tell you that? I don't remember."

"It was a while ago, when he first came here."

"Who, Papi?"

"No, man, the super! Benjamin, not Papi. You deaf or what? Wake up!" Sonny was getting irritated with his brother. The two of them had a difference of opinion as to where the superintendent Benjamin had come from. Juanito was sure that his looks and stature were more in line with a Mexican wetback than with your average Puerto Rican-type. But Sonny knew better, which is why he had asked Papi, who had some intimacy with the man, for clarification.

The super had a son, Benjamin Cardona Junior, the firstborn of his father's three children, the other two being a cute little girl and a tiny baby brother. Everyone knew the oldest as Benny. Benny was a real spoiled brat of a child, a tarnished chip off the old Puerto Rican block. A snotty, know-it-all, "I'm better than you are" type of fellow, roughly his cousins Lucas and Linus's age, which would have made him two or three years older than either Sonny or Juanito. And Benny knew he was a snot rag, too. He carried this chip on his right shoulder, for all the world to see. A twenty-four/seven, pain-in-the-rear-end kind of punkish bully who thought nothing of accosting anyone his age or younger and mercilessly pummeling them for the sheer sake of pummeling. He made any kid's life pure hell on earth, which was why Benjamin Cardona Junior got into more street brawls and fistfights than any other similarly aged juvenile in their South Bronx neighborhood.

You learned quickly that if you didn't get in the first blow - and made it count! - Benny would go at you with tooth and nail and anything else that was convenient or at his disposal. The mystery behind Benny's perpetual sour mood was never resolved. It seemed odd, too, that such a good-looking young teenaged boy, as Benny appeared to be - with the same jet-black hair as his father, but much softer facial features, including a cleft chin and hazel-colored eyes that he obviously got from his highly attractive mother - would behave in such a perversely pugnacious manner. What was he afraid of?

That's what bullies often are, Sonny learned from his Papi. "It's the fear, mijo," Papi would try hard to explain to him. "You see, they always afraid o' somethin'."

"What are they afraid of, Papi? What? They're bigger and they're stronger than me, and they're tougher, too. Who's gonna challenge them about anything?"

"Is not like that. That have a big fear, they afraid of losing the battle."

"I don't understand," Sonny questioned, puzzled by Papi's terse response.

"They fear they gonna lose their status as tough guys. If they go soft, for any reason, they think they lose the respect of everybody. So they always gotta be on the edge, you know? Always lookin' to beat somebody up, to prove they macho or whatever."

"But you're not like that, Papi. Why are they like that?"

Papi looked at his son and displayed a knowing half-smile as he answered him. "You young yet. And you smarter than that Benny. Much smarter. You don' need to be 'fraid o' nothin', you are your own person. You know who you are. You understan'?"

Sonny listened to Papi's explanation and, after thinking about what he had said, realized that Benny was at a disadvantage when it came to facing up to or playing with the neighborhood kids. By virtue of his position as the superintendent's son, in his mind Benny felt responsible for holding up his end as someone who could not be taken for a pushover. Which put him always on the edge. And because that was the case, el joven Benny had no choice but to be constantly on the lookout, to be belligerent and bellicose when he thought it served his purpose.

What a poor state to be in, Sonny felt with a tiny modicum of understanding. A young man, with enviable "matinee idol" good looks, had been forced to duke it out with the neighborhood toughs, just to prove to his old man that he could take care of himself - when that was uncalled for, except in the super's kid's mind. Once Benny gave you that smoldering "evil eye" look, that "I'm gonna kick your ass" stare, your hide was his, or so he thought. Because of his attitude about everything and everyone, Sonny and Juanito, along with the other neighborhood kids, avoided Benny at all costs. He would continue to spell trouble for them as long as his father was the superintendent. And that had to change.

(To be continued) Copyright © 2024 by Josmar F. Lopes