Broken Harbor By Tana French: A Review

I allowed myself the luxury of reading an entire book this week, mostly in my bed, eschewing obligation in favor of pure joy. This afternoon, rather than working, I lay all curled up with an iced coffee and a bowl of candy corn, and finished it.

The book was Broken Harbor, the fourth mystery novel by Tana French, an Irish writer whom I much admire. I first heard about her from Cathy Isaacson, the wife of Walter Isaacson, the biographer of Steve Jobs, and the CEO of the Aspen Institute. “What are you reading right now?” I asked her at a party a few years ago, at a New Year’s Eve party at the aforementioned institute, for lack of anything more interesting to say. I won’t get into the specifics of why I was there, but I certainly didn’t belong.

“A book by Tana French,” she said. She then went on to wax poetic about how much she loved the author. I drop Mrs. Isaacson’s name only because earlier this weekend, when I was in the car with a friend, I launched into a similar soliloquy. “I’m reading a great mystery novel by this Irish writer,” I said. She only feigned interest, so I slipped in the Isaacson name, thereby giving Tana French an intellectual’s legitimacy.

Tana French writes long, complicated, addictive mystery novels set in and around Dublin. I can’t report if they are well written or not—although paying attention during this last novel, I noticed French employs a lot of obvious metaphors—because I get so wrapped up in the stories. They involve some sort of horrible murder, almost always committed with a knife—gun control laws are ironclad in Ireland, which means that knives are almost the only weapon available. To an American, the choice seems both dated and more intimate.

They are driven by a central character—the detective in the police force who is investigating the crime. These detectives, while excellent at their jobs, have a deep, long-kept secret—an emotional trauma that made them what they are today. These secrets intertwine with the crimes they are investigating, clouding their judgement, complicating their cases, oftentimes ending their careers; In In The Woods, the main detective, Rob, investigates a murder on the estate where, 20 years earlier, his two best friends went missing; In The Likness, an undercover investigator, Cassie, avenges the death of her doppelgänger; in A Faithful Place, Frank Mackey refuses to reveal to his superiors that the case he is investigating involves the love of his life, who went missing twenty years earlier, without a trace.

The plots are messy, often overwritten (which, in an era of computer editing and MFA programs, is such a breath of fresh air). They are rife with Irishness and fucked up families—two things that also come intertwined. They are overwrought, emotional, and clearly touched by the hand of a woman who is concerned with the characters she writes. Even if they do evil deeds, she loves them—she sympathizes with their plots, and gives them a fair chance to explain themselves. Most of all, she identifies with them. It’s impossible to know where Tana French ends, and where her characters begin, but there is a sense that if she is not the character herself (Cassie), then the character is a man she fell in love with; a brother; a close friend.

In Broken Harbor, the main character is a little different. Rather than being the underdog, he is the celebrity detective on the Dublin squad. He has the highest close rate in the Murder Department. He’s meticulous—he loves new development housing, blonde women who make for good housewives, and BMWs. His name is Mick Kennedy.

Mick Kennedy, like all of Tana’s other detectives, also harbors a deep secret. He has a crazy sister who pops up in his life, wrecking havoc. He had a mother who killed herself when he was 14, in the beachside town where he investigates the central crime in the novel—the case of a family of four, attacked in a model home. The two children suffocated; the father stabbed to death. The mother, stabbed as well, but still alive, barely breathing.

As the story unravels, so does Mick. Or so, rather, would Tana French lead you to believe. Because it’s hard to read insanity in the language that French uses. This book is not like the others; it’s written too cleanly, too professionally. And all along, you never really believe that French truly got to know, or like, her protagonist (Mick), or the victims.

I won’t say much about what happens—the novel has a plot twist that becomes obvious about 3/4 of the way through. The motive is completely unsatisfactory. I blame it partially on French, either for writing it too quickly, or pumping out a story she didn’t think through, or buckling somewhat under pressure. I hope to god she comes out of it, and writes a Booker Prize-winning mystery.

Mostly, however, I blame it on French’s inability to understand raw, pure madness. Detective Mick’s sister, Dina, is supposed to be completely out of her mind—the book hinges on the dichotomy of nature vs nuture. Is Dina insane because she was born that way, or can’t control it; or is Dina insane because her mother killed herself, and tried to kill her young daughter with her? On a larger scale, this can be applied to the novel itself, which neatly ties into contemporary issues—the economic crisis that caused a recession in Ireland in 2008. Does the family who was murdered have problems because the father and/or mother finally lost their minds to an insanity that lay latent, like a hibernating animal, for many years; or was it the fact that the father lost his job, and all of their savings, and they did what they did to prevent themselves from losing face in the larger community?

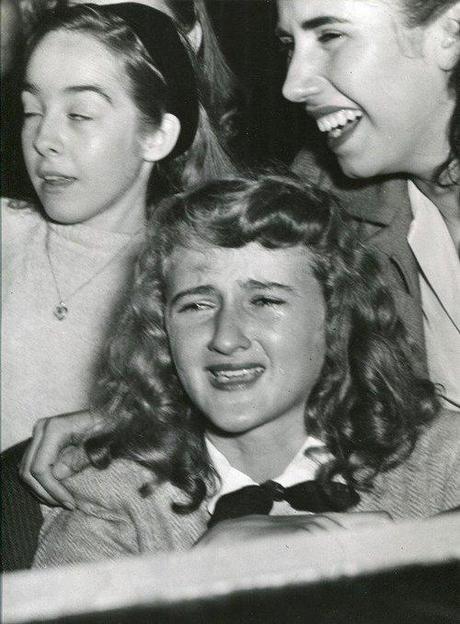

Either way, French just doesn’t get it. I never for one second could picture what Mick’s insane sister looked like; she didn’t speak like an insane person, and her actions didn’t seem organized enough to form a real character. I know what an insane person looks like. An insane person can sometimes look like this:

A young woman with white blonde hair, the bangs burned off at uneven lengths from too many applications of bleach, so that it sticks out at all angles from her forehead, like the hair of a Barbie doll that’s been hacked off like a pair of scissors, stands in front of a window. She’s wearing an olive trenchcoat over a dress over green jeggings, even though she’s at a party. Through the window, in nails topped by fake tips, she holds a cigarette. It burns quickly as she rattles off thoughts.

“I stopped smoking, I swear,” she says to her sister, Beezy, and her best friend, Superbad. Her best friend just lost his childhood companion, 25-years-old, to a drug overdose. “I’m just smoking because I’m so upset that Superbad’s friend died.”

“Do you know what she said to me when she got here?” says Superbad to Beezy. They are lying on his bed, which is in a greenroom on the roof of a penthouse on the Upper East Side. Below them, in the spacious second floor, his father is holding a benefit for veterans with amputated limbs. “Looks like I won the best friend competition.”

“I didn’t say it first, my co-worker said it,” the girl in the window squacks, kicking at Jesse with her foot. “I told her how the last time I saw your friend that died, we had an argument about who was a better friend to you, and she said that now that he’s dead, I won the argument.”

“That’s fucked up,” says Beezy. Superbad begins quietly sobbing.

“Do you think I look good in these pants?” she asks Beezy

“They’re ok, they’re a little tight in the ass,” Beezy says, quickly regretting her honesty.

“Do you think I’m fat?” she says. “Seriously, do you think I’ve gained weight?”

“I don’t know,” says Beezy wearily.

“Superbad,” she says. “Do you think I’m fat? Do I look fat?”

“Yes,” he says.

“You’re such a fucking bitch,” she says to Beezy. “You know that? I was talking to Nana the other day, and she said you’re a fucking bitch, and everyone in the family hates you.”

She starts crying. “You don’t even know how hard it is for me,” she says, and then goes on for a bit about what a victim she is.

After thirty seconds of crying, she immediately re-sets. “Do you think I’m fat?” she asks Beezy. “Seriously, do you think I’ve gained weight?” Then she reaches for a cookie.

“SUPERBAD, GET IT UP!” she screams.

Then she goes over to the computer, and starts randomly changing songs on Spotify. “I love this song!” she screams. “I love this song!”

Five songs and 90 seconds later, she’s lighting up another cigarette, right by the window, talking about the kid who died, and the last time she saw him.

In other words, I can’t write about insanity either.

But what I’m trying to say is that true insanity is fucking boring and repetitive. It doesn’t make for great literature. And when it does, it takes great writing. It takes you paying attention to words, to the way that someone manic, truly unhinged, speaks. In Tana French’s novels, they speak just as lucidly as anyone else.

In any case, you should read all of Tana French’s novels. There’s no pleasure on earth like the pleasure of an addictive read; even if the language isn’t great, even if the plots are overblown, even if it isn’t heavy reading, I promise, they will, at the very least, distract you from your own miserable rhythms.

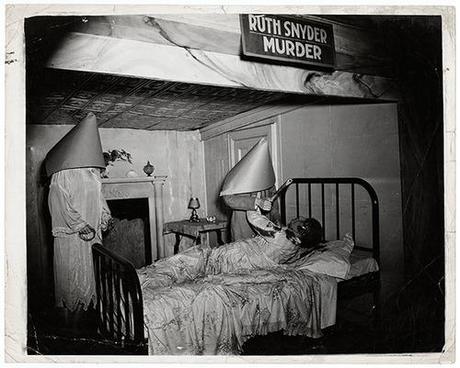

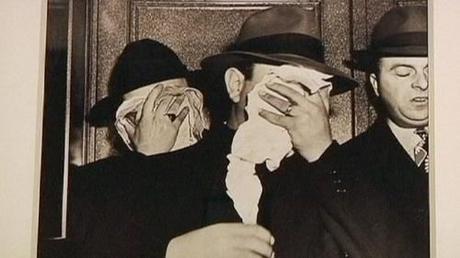

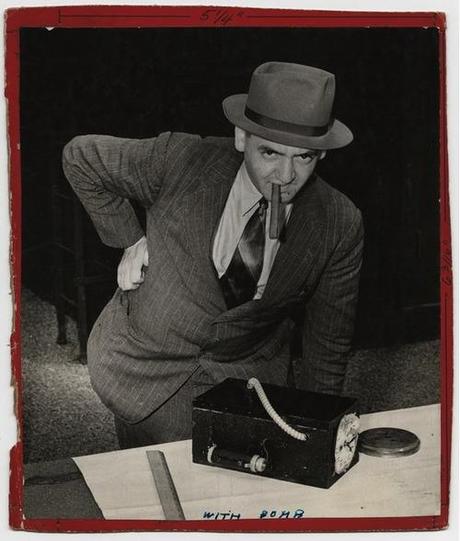

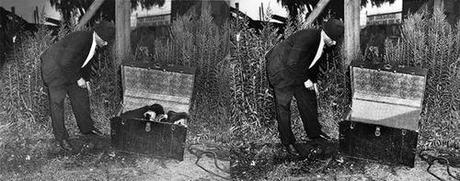

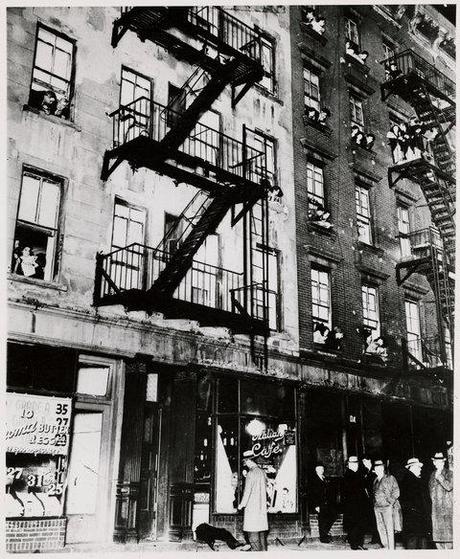

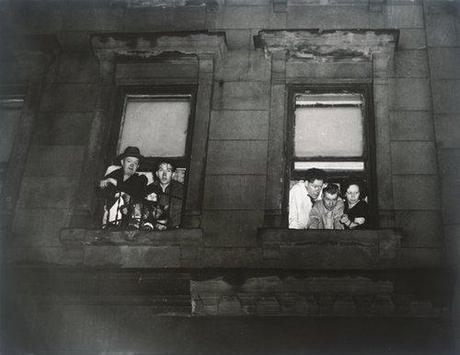

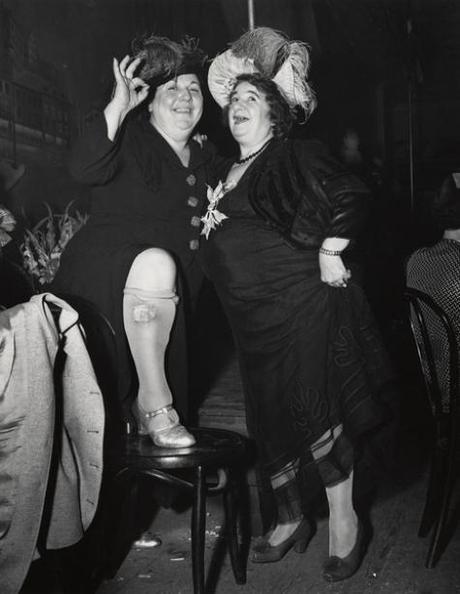

(Most images in this post by Weegee. The first, however, is of Dot King.)