This post is my entry for the Classic Movie Blog Association's Fall 2019 Blogathon. This year we're honoring the CMBA's 10th anniversary with "The Anniversary Blogathon" and participating member bloggers are celebrating all manner of classic film and classic film-related anniversaries. Click here for links to other member posts.

In this piece I take a circuitous look back at Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, "the Citizen Kane of buddy films," on its 50th anniversary.

~

William Goldman

It was during the 1950s that William Goldman, then a young novelist, first got interested in "the Butch Cassidy story." He was so fascinated with Cassidy, ringleader of a late 19th century band of outlaws, and one of his gang members known as the Sundance Kid, that he would research the gang off and on for another eight years.It was also in the 1950s that young "method" actor Paul Newman left the Broadway stage and made his way onto Hollywood's sound stages. Once there, he would steadily be cast in leading roles in films like Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), for which he received his first Oscar nomination, The Young Philadelphians (1959), and From the Terrace (1960).

By the early '60s Goldman was on the brink of a career in film. One of his novels, Soldier in the Rain, was adapted to the screen in 1963 and he was about to add screenwriting to his resume. Newman's career was also continuing upward. He earned a second Best Actor Oscar nomination for his performance in the gritty film The Hustler (1961), and a third Oscar nod for his portrayal of amoral ne'er-do-well Hud (1963). Soon enough the paths of screenwriter and actor would cross for the first time.

In 1965 Goldman adapted Ross MacDonald's 1949 private eye novel, The Moving Target, for the screen. The result would be the screenplay for Harper (1966). Newman starred as Lew Harper, a wily L.A. private eye involved in a mystery as convoluted as The Big Sleep. The film also starred Lauren Bacall, Julie Harris, Janet Leigh and Robert Wagner. It was a big hit.

But the times, they were a-changin'.

In his seminal book on the New Hollywood era, Easy Riders and Raging Bulls (Simon & Schuster, 1998), author Peter Biskind alluded to the domestic and international events that factored into the dramatic shift that hit the movies in the late '60s. It was during that decade that the world's superpowers teetered on the brink of nuclear war, when a young U.S. president was shot down during a motorcade and when the civil rights movement caught fire. It was during those years that the post-war generation, the "baby boom," began making its enormous presence and mounting influence felt, and it was the decade in which a simmering conflict in Vietnam escalated into an all-out but undeclared war.

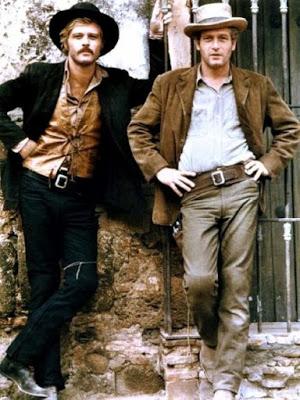

It was while Paul Newman was filming Hombre that William Goldman got in touch and then came to visit him on the set in Tucson. Over several days they discussed the script Goldman brought with him, an original story he then called "The Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy;" until Newman changed his mind, it was assumed he would play the Kid. What Goldman had conceived was a revisionist Western written not as the "sprawling epic" it could've been but as a personal story tied to the bond between two outlaws. The plot followed their exploits, the arrival of the "super-posse" hired to find them and take them down, the pair's escape to South America and their eventual demise in Bolivia. But the key to the story was the relationship between the two men.

Sundance and Butch

It was no secret that Steve McQueen was everyone's first choice to co-star, that he and Newman had met and gone over the script, and that both were interested. There are varying accounts as to why this potentially intriguing pairing didn't happen, but McQueen's departure opened the door for Robert Redford, then a promising but minor leading man. Such is kismet. Director George Roy Hill had convinced Newman to take the role of Butch, a warm, affable charmer who, in real life, was liked by everyone including the Pinkerton detectives. Newman would later admit that he used "a good deal" of himself in the role. Redford was given the role of Sundance, the cool, solitary gunslinger. As Sundance, Redford would dazzle on sight, with his steady gaze and shaggy good looks. More importantly, he would have a chance to prove himself in a plum role. His, like Newman's, was an offbeat character with particular quirks and idiosyncrasies. In Goldman's view, Butch and Sundance had to be "appealing...different and special," that's how he wrote them. Newman and Redford would deliver more than that. The two managed to connect and project a rare mix of chemistry and devastating charisma the movie camera loved. And that audiences would love, too. It was said that without that audience reaction, "there's no picture." Fortunately, the picture was also blessed with Goldman's playful but finely balanced script, Hill's sure direction, Conrad Hall's evocative cinematography and a "semi-modern" score by Burt Bacharach.The super-posse arrives, cinematography by Conrad Hall, editing by John C. Howard and Richard C. Meyer

Disregarding standard Western genre conventions for heroes, heroism, action and romance, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would be fashioned as something more reflective, and more fun, about male bonding, changing times, self re-invention and, with a subtle nod in the direction of Francois Truffaut's Jules and Jim (1962), triangular relationships.

Redford and Newman

One of the film's most striking assets is how deftly the balance of comedy and drama is handled. In the early scenes even the diciest moments of confrontation are played out with wit and whimsy. The tone starts to shift when the super-posse, a pack of gunmen on horseback, bursts out of a boxcar and launches its relentless hunt. Now tension begins to mount and a sense of desperation slowly seeps in. And yet Butch and Sundance continue to banter, though their humor grows darker as their future dims. Goldman would acknowledge his concern that if the film came off as too funny, no one would care when Butch and Sundance died. And he admitted that finding the balance between comedy and drama had been "brutal." Goldman may have suffered, but he found it.Like Bonnie and Clyde, Butch and Sundance got off to a rocky start. The then-important New York critics didn't like it much. But within a couple of weeks, regardless of a lack of significant critical support, the film had become a phenomenon. A blockbuster. The #1 grossing film of 1969 and the #3 box office hit of the decade. Butch and Sundance would earn more than $100 million, that's more than $700 million in 2019 dollars. Redford would later remark that "the critics missed the chord that was hit with the public," referring to the resonant bond between Butch and Sundance. And Goldman would remember the startling impact the film had on the younger generation of the late '60s and early '70s. He recalled a general theory of the time that the movie was actually about the Vietnam war, with the super-posse analogous to the government and "Nixon coming to get you," and the kids seeing themselves as Butch and Sundance.

Toward the end of the film, Etta Place (Katharine Ross), Sundance's lover, tells her man she'll do just about anything for him but she won't watch him die. The decision to depict Butch and Sundance's miserable end in Bolivia with a freeze-frame image rather than a bloodbath was both shrewd and kind. We'd already seen it with Bonnie and Clyde and would see it again many times. Besides, the future of the two outlaws was no mystery, Sheriff Bledsoe had announced it early on when he told the men, "Your times is over and you're gonna die bloody." Thankfully, like Etta, we didn't have to watch.

References

Adventures in the Screen Trade by William Goldman (Warner Books, 1983)

Paul Newman: A Life by Shawn Levy (Three Rivers Press, 2009)

Interviews with Paul Newman, Robert Redford and William Goldman (20th Century Fox, 1994)

Easy Riders and Raging Bulls by Peter Biskind (Simon & Schuster, 1998)