After the veiled satire of Scarface and the open assault of Body Double, Brian De Palma finally caved to pressure and made the sort of film he'd spent the last few years tearing apart. It is unclear whether Wise Guys is the more devastating indictment of '80s mainstream cinema. No, that's mean: there isn't enough to Wise Guys to pick on one way or another. Everything about its concept and execution (not to mention the presence of Joe Piscopo during his brief flare-out in Hollywood) suggests it was one of the first films to deserve the critical shorthand "would have worked better as a Saturday Night Live sketch than as a full movie).

After the veiled satire of Scarface and the open assault of Body Double, Brian De Palma finally caved to pressure and made the sort of film he'd spent the last few years tearing apart. It is unclear whether Wise Guys is the more devastating indictment of '80s mainstream cinema. No, that's mean: there isn't enough to Wise Guys to pick on one way or another. Everything about its concept and execution (not to mention the presence of Joe Piscopo during his brief flare-out in Hollywood) suggests it was one of the first films to deserve the critical shorthand "would have worked better as a Saturday Night Live sketch than as a full movie).The premise is, admittedly, amusing: in the insular, self-contained underworld of the mafia, self-sufficiency must be such a priority than even worthless errands cannot simply be done by someone else without ties to the Family. Then again, enforcers and soldiers aren't going to waste time fetching the don's laundry or getting him groceries, so the poor schmucks assigned with these tasks must be so low on the totem pole they must be the part buried in the ground.

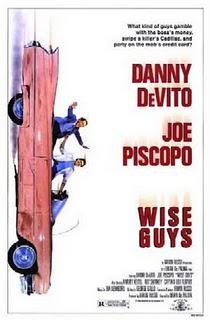

Cue Harry Valentini (Danny DeVito) and Moe Dickstein (Joe Piscopo), an Italian-Jewish double act who got lost in a Scorsese movie on their way to open mic night at Carolines. De Palma almost communicates despair in the film's opening shots, as Harry stands before his mirror reciting the "You talkin' to me?" monologue from Taxi Driver, something that felt tired even in 1986 and shows how half-heartedly the director applies his usual love of quotation and reference. Not even the sound of Harry's young son synching to dad's moment of fun as an unwelcome means of emulating his father (or plagiarizing his plagiarism) that it offers a light chuckle.

That's about the highest level of the comedy in this film. Every now and then, and always in spite of myself, I let out a breath sharp enough to count as a titter, though one could also interpret it as a gasp of sudden, fleeting pain, as if I shifted in my seat the wrong way and pinched a nerve. De Palma's comedies—for as confrontational and arch as they could be, his early films can only be described as such—have always been manic variations on banal people, but Wise Guys instantly sets up an unwieldy dichotomy between its pedestrian setting and drama and the arm-flailing, ham-fisted approach to acting. People in this movie only stop shouting when they make a face so big I can only imagine that they squeezed their vocal cords shut from leaning their heads back too far and cut off air.

Despite the low status of the two men, Harry has fits of grandeur and believes that he can climb the mafia ladder by disobeying his boss to benefit him more. Entrusted with $10,000 by Don Castelo (Dan Hedaya) to bet on a bum horse, Harry dismisses the don's terrible selection and chooses a horse he won money on in the past. Of course, mobsters don't just throw money down on a horse with long odds without currying fate's favor, and Harry's and Moe's jubilation as their horse runs far ahead of the pack gives way to horror when the boss' stallion comes from behind to win. When Castelo finds out, he tortures them and convinces each to murder the other.

Rarely does anything in this film look or sound like De Palma shot it and not any old hack who happened to be hanging around the studio. A split diopter lens makes a shot of Moe and Harry returning to their adjoining homes mildly eerie, the off-kilter dual focus highlighting how the two are as close as brothers but now have a gulf between them as each braces himself to kill his best friend. Later, De Palma heads inside a casino, where the mirrored ceilings recall the fractured visuals of the reflective club walls in Scarface—it's also a cheeky take on his voyeurism, the idea that those ceilings exist for managers to oversee the business instead of the more personal spying De Palma usually does; both kinds are just as seedy, it seems. A handful of other camera shots and movements have spark to them, but the remainder of the film feels like a modestly talented studio hand shot it.

Rather than exploit that tension he packed into that one suggestive, troubling shot of Moe and Harry trying to come to terms with killing the other, De Palma soon dispatches with this thread by letting his two characters in on the punishment, thus making them instantly forget that each seriously considered going through with the assigned task. That leaves about an hour of screen time and no serious way to fill it, so Wise Guys instantly collapses into a cross between GoodFellas and Vegas Vacation. They steal the big mob bruiser's car and run up a huge hotel tab on his credit card, har har har. Maybe their suicide wish would be more plausible if they didn't spend just as much time in hysterics over the inevitability of their horrible deaths.

For the most part, the actors do as well as possible: DeVito has no funny lines, but he commits as if he does and nearly overcomes the obvious, tired nature of the lines, while Hedaya has moments nearly as sinister as those of his conniving husband in Blood Simple. Most surprising is Harvey Keitel as an old friend of Harry and Moe; Keitel, normally a fountain of energy and intensity, acts with fatherly calm here, and his presence prompts a welcome cool-off for the hyperactive movie. Lou Albano, who plays the massive fixer Acavano, actually gets some genuine laughs with his boisterous fury. With his huge frame and flowing suits, he almost looks like Orson Welles in Get to Know Your Rabbit, and his frothing, half-coherent retorts—"I'm a guest of your ass!" he shouts when a polite hotel employee tries to assist him—are so wild they actually match the speed De Palma wants the film's premise to operate upon. Only Piscopo is as bad as the material, his whiny voice and desperate hamming trying to overcome the fear in his eyes, as if he sees that giant vaudeville cane off-camera ready to reach out and drag him to the abyss.

The only remotely rewarding interpretation of Wise Guys is that it shows how cosmically linked Italians and Jews are, despite centuries-old animosity over religious strife. De Palma displays this in primarily reductive means—juxtaposing hectoring wives and a sense of guilt—but if DeVito and Piscopo had more chemistry, they might have dug into that aspect of the film. As it is, there's not much point to Wise Guys, and it lacks any of De Palma's usual redeeming features. It was only a matter of time before the studios won in his war with them, and watching this film, one must thank heaven that the director would finally climb out of the hole with his next, last-ditch effort.