Brian De Palma may be perennially mistreated by a Hollywood that doesn't fully understand where he's coming from, yet I don't know of many directors who have been given so many chances to lose his backers' money. By this stage in his own career, John Carpenter had been all but finished by an industry tiring of his diminishing returns, but De Palma was on just on the cusp of being a validated mainstream filmmaker despite his box office receipts: he'd been given a glamorous gangster picture and a moralizing war film, both of which he infused with his own film-school geekdom even as he demonstrated an ability to play by Hollywood's rules. Having established himself as the '70s film-school leftover best-suited to the decade he'd already mocked with Scarface and Body Double, he finally had his chance to climb to the top.

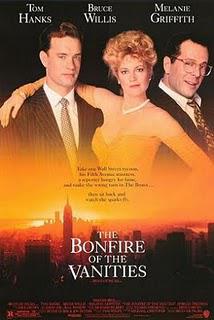

Brian De Palma may be perennially mistreated by a Hollywood that doesn't fully understand where he's coming from, yet I don't know of many directors who have been given so many chances to lose his backers' money. By this stage in his own career, John Carpenter had been all but finished by an industry tiring of his diminishing returns, but De Palma was on just on the cusp of being a validated mainstream filmmaker despite his box office receipts: he'd been given a glamorous gangster picture and a moralizing war film, both of which he infused with his own film-school geekdom even as he demonstrated an ability to play by Hollywood's rules. Having established himself as the '70s film-school leftover best-suited to the decade he'd already mocked with Scarface and Body Double, he finally had his chance to climb to the top.The Bonfire of the Vanities is the apex of the director's late-'80s rise to prominence within the industry, and damn near the nadir of his career. To be clear, it is not as awful as legend would have you believe, or at least, it isn't to me as I've yet to read Tom Wolfe's source novel. I have actually come across some people who not only defend this film but say they prefer it to the book. If that is true, Wolfe's novel must be a real piece of shit. For even without the knowledge of the book's full contents, De Palma's fiasco feels so incomplete and haphazard it's a wonder the director only realized the problems in retrospect.

If Wolfe's roman à clef was meant to be a detailed account of '80s New York in all its schismatic glory, highlighting the split between the budding Wall Street aristocracy and the terror of crack-ridden streets below the high-rise apartments, De Palma's film paints broad strokes of weak satire. No, that's not right; the film only softens one side of the dichotomy between wealthy, oblivious whites and impoverished minorities. Which side gets it easier in the eyes of majority-baiting Hollywood? Oh, take a wild guess.

Tom Hanks, not yet moved beyond his lighthearted comic image, plays Sherman McCoy, a Wall Street investor who makes millions by the minute and enjoys living the life of luxury. Hanks, only a few years out from his dramatic breakthroughs in Philadelphia and Forrest Gump, occasionally flashes an edge that he could have brought to the fore had the screenplay wanted him to truly delve into the seedier aspects of a Wall Street player. Instead, the film uses Hanks' comic charm, portraying him as out-of-touch but not particularly loathsome in any capacity, despite his general celebration of his garish lifestyle and infidelity with a Southern gold digger named Maria (Melanie Griffith). Even when the two accidentally drive into a crime-ridden area of South Bronx and run over one of two black men who accost them, the film does its best to absolve Sherman while placing any blame for the racist and classist attitudes brought up in the hit-and-run squarely on the shoulders of Maria, caricatured out of human recognition into a whining harpy.

This simplified satire might have worked had the same humanizing effect been given to the other half of the film's overview of New York. Instead, poor Sherman, in the wrong place at the wrong time, runs into the undiluted fury of the poor and minority bloc of the city, their grandiose anger exposing hypocrisies and self-defeating extremism while the privileged enjoy a charmed interpretation of white-collar oblivion. The caricature of Al Sharpton, Reverend Bacon, borders on the racist, with De Palma's low-angle shots of bulging eyes and flaring nostrils nearly framing actor John Hancock in minstrel poses.

Bacon rails against the notion of the unidentified driver of a Mercedes getting away with the cops' indifference, rightly noting that they wouldn't just drop the case if some black driver had run over a middle-class white family. But like Sharpton or Jesse Jackson, Bacon is as much a self-promoter as he is a civic crusader, and he clearly plays up for the cameras to make himself the focal point of the manipulated outrage. But he's successful, and soon he's got Weiss (F. Murray Abraham), the D.A. looking to for a way to win the minority vote after prosecuting minorities overwhelmingly, quaking in his suit. Abraham removed his name from the billing over a contract dispute, but part of me wonders if he did so after reflecting on his performance. If Hancock must make out the leaders of the black community to be nothing more than charlatans looking to crucify a white devil to maintain their stats, Abraham plays Weiss as a flagrant Jewish stereotype, greedily hunting power and also looking for a way to get one up over on the WASPs. When Bacon accuses him of letting the wealthy white go unpunished, Weiss frets over being seen as a "hymie racist pig," then muses aloud how the Italians, Irish and WASPs will love to see him squirm.

Obviously, this is satire, but it's paper-thin, and De Palma inserts nothing to offset the racist view of the city's minorities being wholly self-serving. Instead of flecking human beings with ironies and contradictions, he presents two-dimensional caricatures with comedy that isn't funny enough to absolve the troubling simplicity of their ethnic identities. Pointing out the class blindness that affects the underclass is a perfectly valid criticism, but here the blacks and Latinos come off as nothing more than a mob looking for a white scapegoat. And even when De Palma finally gets down to going after the elites—presenting them as entertained by Sherman's connection to such a pedestrian crime like Roman nobles approvingly watching enslaved gladiators torn to ribbons—he still lets Sherman almost completely off the hook. At the ridiculous trial that closes the film (presided over a black judge instead of the book's Jewish one so as to make Sherman's acquittal seem victorious rather than proof of the system stacked against non-whites), poor, frail Sherman is framed against a screaming, hissing, even singing (hymns, natch) crowd of the poor and pigmentally varied. Whether the De Palma meant it or not, and the swelling, unironic strings that accompany the verdict suggest at least someone did, the audience is meant to root for McCoy to get off Scot-free.

This is all bad enough, but various other additions weigh down the film in subtler ways. The film nearly approaches cleverness when Sherman attends a performance of Don Giovanni and clearly sees himself in the character, a point De Palma then drives him with a sledgehammer, ruining the one good part of the film. Bruce Willis, foisted upon De Palma and a noted pain on-set, plays the alcoholic reporter Peter Fallow, who desperately launches the hit-and-run case to give himself a popular story to justify the paychecks he drinks every day. Whatever role Fallow played in Wolfe's novel, he has no reason to exist here, and De Palma must resort to a framing device that awkwardly inserts him into the movie so Willis can deliver stiff voiceovers in that noncommittal drone of his.

The Bonfire of the Vanities is so clumsy that even the moments of pure De Palma fail to add some life into the film. A swirling overhead shot of Sherman and a coworker is an ingenious touch that makes great use of the striking floor design, but it only goes to show how little time the director spends in Sherman's corporate world. A split-screen between Bacon's self-aggrandizing harangues and a changing right image first showing an amused Fallow looking on then a nervous Weiss watching on TV feels like someone trying to ape De Palma with no regard for composition or juxtaposition. Even the elaborate, wildly entertaining tracking shot that opens the film, following Fallow as he arrives for a speaking engagement through the underground of a complex past admirers and pack reporters, fails to maintain its power when placed in context with the rest of the movie. When the film soon moves completely away from Fallow for an hour, the shot, maybe even Fallow's entire presence in the film, seems a self-serving addition.

After filming completed and The Bonfire of the Vanities went out to a critical and commercial savaging, De Palma finally admitted his error, even letting Julie Salamon come in and write a tell-all on the film's troubled production. I want to read that book as much as Wolfe's source novel: even a basic summary suggests studio tampering, uncooperative stars and wasteful expenditures. But hell, all of that is visible on the screen. It is stunning that a filmmaker as radical (aesthetically and politically) could make a film so firmly reactionary in its ultimate absolution of the luxury class—compare the subverted race roles of the "Be Black, Baby" segment of Hi, Mom! to the clearly demarcated racial cartoons drawn here. Almost as unforgivable, it's one of the director's dullest films. Even the "punchline"-lacking Untouchables (to take a page from Pauline Kael) felt more alive than this.

The only good thing I can say about The Bonfire of the Vanities is that it sports simply one of the greatest shots to ever appear in a De Palma film, a perfectly, almost freakishly timed shot of a Concorde jet landing at sunset as the landing strip aligns perfectly with the descending orb. It is a stunning, arduously planned moment, and it's the best indication of how much better the film might have been had De Palma and his crew been given a better cast and screenplay. From what I can tell, a more accurate representation of Wolfe's novel might have been right up De Palma's alley; he would have delighted in tearing everything apart. Instead, he made by far his most reactionary film, a lighthearted spoof of the upper class and a vicious portrayal of the poor and disenfranchised. Had De Palma not made his mea culpa later, I might have thought he did this on purpose; his other big Hollywood spectacle, The Untouchables, is also conservative. But even the wide berth I give to De Palma's irony has its limits, and if The Bonfire of the Vanities was meant to be as bad as it is, well, mission accomplished.