The mainstream view of Brian De Palma's 2000s output is anything but flattering, with all four of his films made in the new millennium bowing to intense critical pans and commercial indifference. However, I've found his contemporary work to rank among his best. Mission to Mars captures the boundless enthusiasm (and unabashed cheesiness) of old Disney space adventures, shot to favor near-poetry over scientific accuracy and all the better for it. Femme Fatale threw people with its narrative mulligan, but it made the strongest case to date for the director's actual feelings for women, which are far more complex than the lazy accusations of misogyny that have dogged him for so long. The Black Dahlia is, if anything, the only one of De Palma's films that can even stand with Carlito's Way in terms of sheer aesthetic and Romantic beauty. Its sloppy elements and awkward acting choices only add to its deliberate, yet gentle, attack on Hollywood. It may also be the most neatly contextualized of De Palma's films in his strange canon, fitting neatly with the more formal, big-budget experiments and the uncompromising anti-mainstream tone of his '70s and '80s work.

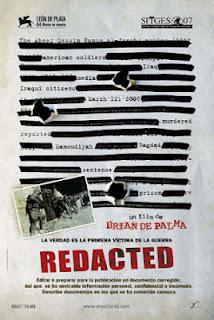

The mainstream view of Brian De Palma's 2000s output is anything but flattering, with all four of his films made in the new millennium bowing to intense critical pans and commercial indifference. However, I've found his contemporary work to rank among his best. Mission to Mars captures the boundless enthusiasm (and unabashed cheesiness) of old Disney space adventures, shot to favor near-poetry over scientific accuracy and all the better for it. Femme Fatale threw people with its narrative mulligan, but it made the strongest case to date for the director's actual feelings for women, which are far more complex than the lazy accusations of misogyny that have dogged him for so long. The Black Dahlia is, if anything, the only one of De Palma's films that can even stand with Carlito's Way in terms of sheer aesthetic and Romantic beauty. Its sloppy elements and awkward acting choices only add to its deliberate, yet gentle, attack on Hollywood. It may also be the most neatly contextualized of De Palma's films in his strange canon, fitting neatly with the more formal, big-budget experiments and the uncompromising anti-mainstream tone of his '70s and '80s work.Then there's Redacted. In 1989, De Palma made Casualties of War, one of his most sincere films and perhaps the only one to lack any postmodern flourishes. Redacted seeks to rectify this: it swaps Vietnam for Iraq and swaps the classical filmmaking of Casualties for a collage of styles and media. De Palma constructs his film as a hodgepodge of footage sources. The intent is clear: by stylistically and narratively repurposing Casulaties' true story of a rape and massacre being arduously brought to light, Redacted uses its own dramatization of real events to demonstrate that, in a war that can now be documented by anyone with a cell phone, truth has never been further from the public's grasp. If Casualties of War found worth, even moral victory in doing the right thing, Redacted nihilistically sees no point in even trying.

For that very reason, all the incisive ideas percolating through Redacted's slim running time cannot prevent it from being one of the most abysmal, unbearable movies De Palma ever made, ranking among the dregs with Bonfire of the Vanities and Wise Guys. It's a shame, too, for Redacted occasionally flirts with greatness, suggesting a vicious assault on oblivious American mindsets since the "Be Black, Baby" segment of Hi, Mom! But from the first moments, one can tell that Redacted will be a miserable chore, not a galvanizing screed.

The film follows a company of soldiers stationed in Iraq, where they already chafe under the hot desert sun and tense relations with the indigenous population. One soldier, Angel Salazar (Izzy Diaz), decides to film life on the base, believing that his work will get him into film school when he goes home. There's a grim irony to this thought process, the home videos a young Steven Spielberg used to make where he and his friends reenacted war now replaced by a taping of a real one. But his journal reveals the first, and deadliest, flaw of the movie: Salazar, and his comrades, could not be more simplistically written or agonizingly two-dimensional. To a T, they make casually racist comments about Iraqis and show no remorse for their lethal screw-ups. A green soldier ends up killing a woman at a checkpoint when her car speeds through, and not only does he not struggle with it, he brags into Salazar's camera.

Only Salazar and another soldier, Lawyer McCoy (Rob Devaney), ever even hint at a basic humanity, and they are no more nuanced than their rapacious brethren. They are moral simply because the script calls for someone to be at least partially decent, and their protests to increasingly horrific behavior have all the conviction of a bored high-schooler forced to read a play aloud in class and doing so with a flat, get-it-over-with monotone. The squad leads a raid on a local home that they suspect contains intel, where they arrest a man for no reason as a reporter for an Al-Jazeera-like news organization asks the soldiers what they are doing. Later, some of the soldiers decide to return to have their way with a 15-year-old girl they saw in the house, killing her and her family in the process. Salazar is forced to witness it, and a protesting McCoy is thrown out by his comrades at gunpoint.

That's the basic gist of the story, but De Palma tries to dress it up with his use of multiple styles. Unfortunately, the result is an interminable mess. De Palma's asides with a group of French documentarians parody stuffy, emptily moralistic war docs, the camera slowly zooming in and out on soldiers' faces as the orchestral arrangement of "Sarabande" from Barry Lyndon plays. At least, I assume it's a parody; these segments are so tedious that De Palma must be making fun of such films, but his target is unclear. Likewise, we see various YouTube clips of terrorists sneaking bombs under the clueless eyes of the Americans, or of newscasts showing angry Iraqis swearing vengeance for what has happened to them. Everyone knows what the Americans are doing, but no one will listen.

It might be an compelling array of conflicting, yet harmonious, elements were the transitions not so jarring, the morals not so disgustingly black-and-white, and the judgment not so haughty. Casualties of War grounded its characters' sadism in an understanding for their predicament. It vigorously condemned the actions of the soldiers, but it could also at least see how they were driven to the point of feral madness. Redacted feels like an old man's rant about "kids these days," only the kids here murder a family in cold blood and set fire to a teenager after raping her. It just accepts the horror of the soldiers' actions as a foregone conclusion. Salazar blanches at the atrocity, but he also wants to reveal the truth in a way that will make his film project a hit; better to get back home and piece together a dynamite cut than get justice now. And all McCoy can do is feel bad, even up to his last moment on-screen, which openly mocks him.

War is unpleasant, and the Iraq War more unpleasant than most, given its falsified justification and mismanagement. But De Palma's usual talent for immersion in seediness fails him here. He does not capture the repulsion of war; he only makes a repulsive film. As if to ward off the pointlessness of the exercise, De Palma has his characters occasionally spout aesthetic maxims. When Salazar jokingly tells McCoy that his camera doesn't lie, McCoy replies, "That's bullshit because that's all that camera ever does." Later, Salazar more insistently urges, "Just because you watch it doesn't mean you're not a part of it." Naturally, both of these utterances are key positions of De Palma's entire approach and philosophy, but so hear them said aloud here cheapens them. Especially the latter quote; De Palma is a master of implicating his audience, up there with Alfred Hitchcock and Michael Haneke. But this film does not implicate anyone because it is so morally rigid. Casualties of War shows a situation slowly spiraling off its axis until the breaking point isn't visible. These men broke before they even left home. What, then, can we learn of them?

And why is the movie so unsparing? As with the Incident on Hill 192, the real-life Mahmudiyah killings were punished. In fact, they were punished far more severely than the incident that spawned Casualties of War. The soldiers who raped the Vietnamese girl and destroyed her village had their sentences drastically reduced, and in some cases dropped entirely. The three soldiers involved in Mahmudiyah, however, have received multiple life sentences. To end the film on an uncertain note is just bullshit posturing, an offensive recalibration of reality to fit a tidy, repellent premise. The problem with this film is that De Palma, though still a provocateur, cannot now conjure the same anarchist energy of his earliest days. When he inserts an embarrassing YouTube rant by a single-minded teenage liberal, he does not broaden the scope of his critique of contemporary culture. He merely chucks in one more stereotype to be lazily jabbed, nothing more than the wink of a shock comic grown too old.

There are so many good ideas in Redacted. The fat soldier's first raid through the house borders on the Orwellian as he seizes documents he cannot read for evidence so that he can give them to a translator to determine if they are actually evidence. The blood stains left by the dead recall those thick lines of permanent marker blacking out sensitive information, erasing the full detail of the person who was there while still leaving an unmistakable trace of malfeasance. The cross-format collage of video sources presages Film Socialisme in a Derridean attempt to chase truth through the multitude of options now available to us and coming up shorter than ever. But the lapse of De Palma's subtlety results in a film that feels like a repository for every charge ever leveled against him, from misogyny to cheap cynicism to hollow rip-offs (the music lift from Barry Lyndon and a recreation of the scorpion and ants shot from The Wild Bunch add nothing). Many of De Palma's films have vile traits, but they are usually intentionally added, well-illustrated travesties cleverly dismantled by De Palma, who can be in the thick of it and above it all at once. This, however, is the only one of his films I've ever found truly disgusting, and I hope that he gets back to work soon to erase the memory of it.