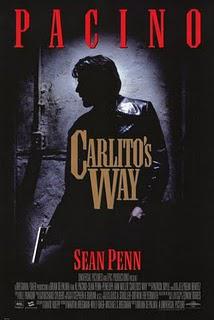

I used to think Carlito's Way was, to quote the popular interpretation, an "apology" for Scarface, a toned-down, mature take on that film's criminal excess that depicts a gangster trying to redeem himself rather than climb the ranks of the underworld. After revisiting that film, however, I can better see what De Palma was doing with his first, more grandiose view of the criminal underworld and, with unorthodox focus, how it affected America's rising Latino population. Nevertheless, this film, with its ever-moving but graceful camera, bold use of color and flagrant romanticism, not only proves the superior view of criminal life but also stands as perhaps De Palma's finest achievement as a filmmaker and the best balance of his confrontationally probing camera and the mainstream Hollywood elegance of which he wanted to be a part.

I used to think Carlito's Way was, to quote the popular interpretation, an "apology" for Scarface, a toned-down, mature take on that film's criminal excess that depicts a gangster trying to redeem himself rather than climb the ranks of the underworld. After revisiting that film, however, I can better see what De Palma was doing with his first, more grandiose view of the criminal underworld and, with unorthodox focus, how it affected America's rising Latino population. Nevertheless, this film, with its ever-moving but graceful camera, bold use of color and flagrant romanticism, not only proves the superior view of criminal life but also stands as perhaps De Palma's finest achievement as a filmmaker and the best balance of his confrontationally probing camera and the mainstream Hollywood elegance of which he wanted to be a part.This mix of the daring with the quotidian might explain why so many mistook the film for a mildly original take on a tired subject. But to see how the film subverts and analyzes clichés, one need look no farther than the opening, a monochromatic framing device that spoils all pretense at suspense by showing the titular hero murdered by way of introduction. De Palma uses the sequence not only to set in motion his aesthetic approach—using his Steadicam shots as POV representations of Carlito's view, up to and including the slow pivot upside down and pull back as Carlito's soul leaves his body—but to make sure that we spend the film not wondering what happens to Carlito but why this doomed scenario occurs.

As the film moves into flashback, we see Carlito (Al Pacino), a convicted heroin dealer, getting out of prison after serving five years of a 30-year sentence. His lawyer and friend, Dave Kleinfield (Sean Penn), gets him off not for good behavior or truly appealing the case but pointing out D.A. corruption. Pacino uses the court scene to get out his hoo-hah mania he exhibited in the previous year's Scent of a Woman (a movie I maintain is Animal House with stunt casting and a sense of self-importance). He carries on about being a changed man, shouting over the judge who has to take it because he, too, was complicit in the evidence tampering that put Carlito away. "I've been cured! Born again, like the Watergaters," Carlito shouts gaily and sardonically, and it's impossible to see the sincerity underneath his spiel. But Pacino soon calms down, and his Carlito proves to genuinely wish to quit the game, to quietly exit the world where he built up a considerable reputation.

The contrast between Tony Montana and Carlito Brigante is less a means of making one a response to the other but of establishing them as polar opposites. Tony, young, brash and oblivious, climbs the ranks of Miami's criminal underworld through sheer brutality. His mantra, "The World is Yours," summarizes his approach: seize power until you sit in a king's throne, regardless of what you sacrifice to get there. Carlito, on the other hand, is older, wiser and wearier. Like Tony Dayoub says in a brilliant piece tackling the mirror effect of the two films, he is "almost but not quite the elder statesman Tony could have grown into had he outlived his impetuous youth." Tony also noted the color-coding of the two Hispanic protagonists, a key reversion of usual white-black color significance. Tony, who wears ostentatious white suits, is the villain, his clothes reflective of his drug of choice, his desire to be seen in Miami's underworld and, perhaps, his attempt to join the privileged race he thought he could by and screw his way into. Carlito, the one wants to get out of the game and go straight, wears stereotypically villainous black. But this is his futile means of trying to disappear in his surroundings, hoping to quietly move out of the underworld after becoming disillusioned with it. Carlito just needs $75,000 to retire. Tony Montana spent more on wing collars.

But, of course, one does not merely walk away from crime, and De Palma highlights the naïveté of this facile camouflage by colorizing the mise-en-scène to such an extent that the film occasionally looks like it came right out of Old Hollywood. Blue-lit nights expose him, as do the bright-red walls of smoky dives and the chrome-plated realm of the nightclub Carlito invests in to raise the money he needs to escape to the Caribbean for a new start. (Incidentally, the club, El Paraiso takes its name from the food stand Montana opened in Scarface). That club brings out the fatalistic romanticism of the movie, a weak approximation of Carlito's escapist fantasy that looks like a mock-up of a cruise liner interior and feels, for all its coke-addled disco dancers, more like a perpetual high school dance than a cesspool of drugs, sex and crime. The innocence under its veneer of tacky '70s "class" somehow makes the place more constricting and repellent, as if the building too is aware of its fate but still locked into its servicing role.

That romanticism explodes as Carlito tries to make his peace with former partners and to rekindle a relationship with Gail (Penelope Ann Miller), a dancer with whom he broke up before going to prison. He did so not to hurt her, but he broke her heart anyway, and the chemistry between Pacino and Miller subverts the usual male chauvinism of the mob world: when he first tracks her down, Carlito stands on a rooftop across from the dance studio in the pouring rain holding a trashcan lid over his head as a low-rent umbrella. In this moment, De Palma's appropriation of Hitchcock's voyeurism transmutes from obsessive quest for power into pure, innocent longing. This is not a man who feels his love "belongs" to him but someone who never stopped caring for her. After they reconcile, Carlito watches her dance with another man with a smile on his face, completely non-threatened by the harmless display, even when other men raise objections to seeing his woman dance with someone else. Carlito feels like a better man around her—note that Montana wanted to feel white around Elvira, who constantly brought up and mocked his Hispanic background, while Gail is the only person to call Carlito by the Anglicized name "Charlie"—and one almost forgets the inevitability of his attempts to escape when watching the two of them plan their retirement.

Yet Gail soon discovers how trapped Carlito is within the system, and her voiced complaints often make plain the self-evident truths Carlito cannot quite see. For all his talk of not recognizing the mid-'70s world of cocaine and disco in relation to the sociopolitical revolution he left behind, it is Carlito, not everyone else, who has changed. Bound by a code of honor not to rat on his allies and to remain loyal, Carlito never snitched on his old partner, who appreciates the gesture but feels no financial or personal debt to his old partner despite the fact that he got filthy rich while Carlito was away. For all Carlito's efforts to avoid violence and crime, such things seem to find him anyway. He gets roped into going to a drug deal with his young cousin that goes awry, and later he must deal with Benny (John Leguizamo), an upstart little shit clearly looking to make his name by tearing down Carlito. Benny is reminiscent of Tony Montana, a connection that then links back to Carlito when another gangster accurately tells Carlito "This guy is you 20 years ago."

Torn between his sense of code, his awareness of the vicious nature of the streets and his desire to go straight, Carlito can't ever seem to win: he reacts stubbornly when he shouldn't, agreeing to help an increasingly unstable Dave settle his own debts out of the loyalty he owes the lawyer for springing him. On the flip-side, he shows clemency for Benny, the man who, frankly, he should have killed, an idea that antithetical to a normal sense of morality*. But we're talking about the criminal world, where rules have been warped and ethics muddied. Bewildered by these conflicting notions of right and wrong, Carlito occasionally voices his pressure, saying, "The street is watching. She is watchin' all the time," as if the city itself is bearing down on him, waiting for his moral tug of war between desire for self-improvement and perceived obligation to others to stretch him to the breaking point before delivering the coup de grâce.

To De Palma and writer David Koepp's credit, they do not let Carlito off the hook for wanting to do the right thing. In the aforementioned drug deal with his cousin, Carlito knows instantly that something is off in the bright red pool hall where the deal occurs. De Palma's camera has rarely been better as it sets up Carlito as a knowledgeable killer. Just because Carlito wants out does not mean he was just someone who got caught up in the trade: as POV shots dart to an ajar door where a thug awaits and the camera moves around the pool table as Carlito sets up a trick shot as an excuse to keep circling and take stock of the whole room, we see how professional he is in this underworld. He's skilled enough to know what's about to happen and to position himself to kill his way out of the situation. In The Godfather Part III, Pacino's Michael growls, "Just when I thought I was, they pull me back in," but that is just Corleone's usual obliviousness to his own culpability. Carlito is not someone who just "made a few mistakes" in life, but he genuinely wants to reform where Michael wishes to have his cake and eat it too. It is Carlito, far more than Michael, who is trapped by something not of his design.

By the same token, it's almost impossible not to sympathize with him, also as a result of the most elegant camerawork of De Palma's career. He creates a tone so romantic that a conversation between Carlito and Gail through the crack of a chain-bolted door is not intimidating but teasing and charming, to the point that when he kicks the door in after a playful striptease involving a mirror, it's a comic, even loving payoff rather than a tense moment of sexual dominance. De Palma has used a circling shot more than once, but here the camera actually dips and tilts as it revolves around the kissing couple, swooning with them. The camera moves incessantly but does so with grace, a beauty that feels far more natural than the more forced and restrained formalism of, say, The Untouchables. At last, De Palma finds the perfect balance between his mainstream aspirations and his underground, morally probing aesthetics, a union bolstered by the fact that, for once, De Palma is using his camera to poke around the moral implications of his characters in a wholly un-ironic fashion. It's not the first film of his to be sincere, but it is the first to channel his penchant for deconstruction entirely into the characters and genre clichés, gently picking apart stereotypes to see the humans who inspired them.

But even with De Palma's masterful camerawork, the film wouldn't work without an understanding lead performance, and Pacino clearly demonstrates he knows exactly where De Palma is coming from for the second time. He acted like a Pre-Code madman in Scarface, but here he is so gentle that I remember the softer, vulnerable side to Pacino from the '70s. In his prime, no one had better control of what he could say solely through his eyes, and that skill returns here. His longing, anger, despair and fantasy dances across his face in beautifully understated terms, and he delivers lines with quiet force. I don't know that Pacino has ever been more heartbreaking; his whole performance is like the look of devastation on his face in Dog Day Afternoon when his lover publicly rejects him, stretched out over two and a half hours. When he first hugs Gail after reuniting, he softly smells her, triggering his memory with its most connected sense, and his ragged breath is as stoic a display of unspeakable joy as exists in the movies. When Dave drags him into a ludicrous attempt to bust an Italian mob boss out of prison, Pacino's face registers disgust more than anger at the addled lawyer's horrific change of plans and eventual betrayal, a recognition of the uselessness of the code that binds him and seems to let everyone else behave as he pleases

Reveries and dreams have always been a staple of De Palma's films, but usually in a literalized, nightmare form. Here, the dreams are less literal and more yearning, and the only nightmare comes with the impossibility of their fulfillment. A symbolic shot of Carlito trapping a cockroach under a glass and letting it go reflects the error of leaving Benny alive and outraged, but the roach might as well be Carlito, trapped at the mercy and amusement of forces so vast they feel existential. The film climaxes with a nimble cat-and-mouse chase through the subway that ends in the only dastardly cruel twist in the film, impressive considering we know the true outcome already. But as the film returns at last to its framing device as Carlito fades from this world, the last shot settling on a billboard advertising a Caribbean getaway. As Carlito dies, the subjective view of this poster alters, the woman dancer frozen in a snapshot suddenly turned into a dancing Gail, the dream fatalistically actualized in hallucination. As this shot holds over the credits, Joe Cocker's "You Are So Beautiful" begins to play, the gravel-voiced singer undercutting his ode even as the pained growls make it all the more sincere. It's the perfect swan song for the film, a plaintive yet doomed piece of (capital- and lowercase) romantic genre film, in which the last shot is both bitter and beautiful. In a sense, Carlito's Way may be the cruelest film De Palma, who delights in tricks and dramatic catastrophe, ever made, a lengthy explication of a dream that does not come true. But if it is so rending, that is only because, better than any other film in his canon, the director makes us truly care for his characters, and his cosmic sense of irony is at no one's expense, save poor Carlito's.

*Elsewhere, though, Carlito's clemency is more justifiable and even redemptive. An old associate (Viggo Mortensen), now paraplegic from being shot, wears a wire to a conversation with him as the D.A. looks for any excuse to put Brigante back in jail. By rights, Mortensen's character should be promptly shoved into the nearest river tied to a concrete wheelchair. But Carlito relents: he looks at the man who has had so much taken from him by the life Carlito has come to despise, and he pities the paraplegic wreck. Not only is it a true moment of forgiveness, it is also a practical moment of conscience compared to the fatal mistake of letting Benny go: releasing Lalin is a shrewd move that proves to cops that he really is reforming, not simply grandstanding to return to crime.