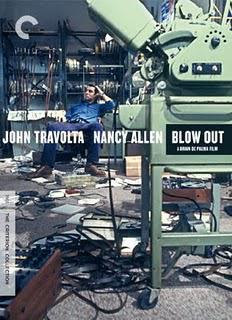

Blow Out represents a breakthrough for Brian De Palma. After farcically and satirically pulling apart the bonds of cinema for nearly two decades, the self-reflexive director at last found a way to incorporate cinema into a narrative without breaking up the movie. There are still jokes in Blow Out, but they tend to be of the cosmic variety; the closest anyone comes to an outright punchline is one character's innocent assertion "I don't watch the news. It's too depressing." Instead, De Palma structures his gags as dark, wordless payoffs, all of them carrying a bitter, emotional irony that feel like punches to the gut, something only rarely felt in De Palma's canon up to this point.

Blow Out represents a breakthrough for Brian De Palma. After farcically and satirically pulling apart the bonds of cinema for nearly two decades, the self-reflexive director at last found a way to incorporate cinema into a narrative without breaking up the movie. There are still jokes in Blow Out, but they tend to be of the cosmic variety; the closest anyone comes to an outright punchline is one character's innocent assertion "I don't watch the news. It's too depressing." Instead, De Palma structures his gags as dark, wordless payoffs, all of them carrying a bitter, emotional irony that feel like punches to the gut, something only rarely felt in De Palma's canon up to this point.As with Dressed to Kill, De Palma does open his film with an extended gag, in this case a POV shot of a mouth-breathing killer stalking a sorority hall, his magnified breathing and racing heartbeat raising tension as scantily clad coeds fail to notice him. At last, he moves into a Psycho pose in the shower, pulls back the curtain, raises the knife, and the woman lets out the most hysterically fake scream you ever did hear. The camera shifts to tripod-mounted third-person in an editing studio for exploitation features as soundman Jack Terry (John Travolta) chuckles at how bad it is to his teed-off boss. What was I saying about this not being a funny movie?

Tasked with finding new sounds to overcome the stale effects library, Jack heads out to a local park at night to get ambient noise, his microphone resembling a gun or a conductor's baton as he points it at various noises. Suddenly, he hears the tires of a car squealing and turns in time to get crisp audio of a loud bang as the car's front tire blows out and sends the vehicle careening off a bridge into the water below. Jack dives in and saves a woman, Sally (Nancy Allen), but the man inside died on impact. In the hospital, Jack learns that the man was Gov. McRyan, the front-runner against the president in the upcoming election.

An aural riff on the photographic obsession of Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow-Up, Blow Out also incorporates De Palma's usual love of Hitchcock, as well as the political thrillers of Alan J. Pakula. But where Pakula's camera generally remained still, conveying the threat of an overlooking presence so vast it bordered on the gnostic, De Palma's camera is that of a stalking predator, always following but remaining hidden. Pakula's forces create their own shadows; De Palma's must slink around in the system as it is. He uses split diopter lenses to give equality clarity to objects in the foreground and in the distance while still emphasizing the space between the two. At the park, the objects Jack records dominate the foreground as Travolta stands outside of space and time recording them from afar. Later, the sidewinding tracking shots present a growing grace in De Palma's form, less showy and more substantive: Burke (John Lithgow) an assassin tying up loose ends, stalks a woman through a market. De Palma visualizes this through elegant tracking shots that eventually move to settle in a close-up of a fish and a meat thermometer in the foreground in time for a hand to pick up the sharp-needled thermometer.

If the director back-pedals on his usual cheek, he at least retains his penchant for irony, which abounds here. De Palma introduces McRyan by way of a newscast reading out his staggering poll numbers at the beginning as Jack cuts new audio in his apartment, his loop of thunder portentously rumbling underneath the newscaster's discussion of the governor. As the film's plot thickens, red, white and blue dominates the color palettes in falsely patriotic ways; even the slasher in that film-within-a-film at the start wears a red, white and blue jacket. The director even sets the whole film against an anniversary celebration involving the Liberty Bell, but his view of the grimy, neon-streaked streets of Philadelphia robs the patriotic commemoration of all meaning. The only true uses of the Liberty Bell in the film involve Burke's disturbing stab pattern as he invents a serial killer persona to cover his tracks and in a chase at the end wherein Jack spends straight through the anniversary parade without taking a second glance at the proceedings, highlighting the secondary if not tertiary importance of such an event to a post-Nixon America jaded on the supposed greatness of our institutions.

The disregard Jack shows for politics in that early moment of him playing the TV as background noise shifts when he becomes convinced he heard the sound of a gunshot before the tire blew out, and soon he finds himself mired in a political conspiracy. Advised by a McRyan staffer to let the whole thing go and pretend Sally was never there to spare the governor's family embarrassment, Jack suddenly commits himself to getting out the truth.

But who will listen to him? Unlike the crusading journalists of All the President's Men or even the less scrupulous reporters of The Parallax View, De Palma's characters are the refuse of society. Jack records the effects for video nasties; Sally more or less works as a prostitute despite her desperate attempts to demarcate the blackmailing racket she's exploited for from outright whoring. They have no forum, no access, no means of telling people what happened, or any way to confirm anything happened at all.

Deepening Travolta's character is the revelation that he once served as a communications officer in the Army and later helped in a government crackdown on corrupt cops, thus linking him to politics outside these events. In a flashback, we see his failure to look out for an undercover cop who wore a wire to expose his colleague's mob collusion, and De Palma tacitly posits Jack's inability to save the man as the impetus for his going into film, where reality can be shifted at the push of a button and a few judicious uses of a razor blade and glue.

The nature of filmic truth becomes a recurring motif of the film: that jarring gag at the end of the opening segment serves as a breaking of the fourth wall even before the camera pulls back into the studio. It shatters the moment, connoting to the audience that it's not real, even within the film's world. With the flick of a few switches and dials, Jack and the other filmmaker can add or remove sounds, completely altering the tone and perception of the scene. Later, when Jack gets a hold of film a seedy blackmailer took of the "accident," he finds a way to splice in his audio at the right time to find out the truth, his constant replays and rewinds showing him trying to reverse the turn of events.

But, of course, he can't change reality, so the best he can hope for is to get the word out before someone gets to him. Intriguingly, Blow Out readily acknowledges that a conspiracy exists, unlike a number of such thrillers where directors seek to leave open the possibility of overactive paranoia. De Palma, radical leftist whose brazen politics were so visible in his early, underground work, is so cynical that he just knows that people are out to get Jack. What he leaves blank is who wants to cover up the event. Both shady government forces and supporters of McRyan put pressure on the narrative: the opposition wants to cover up involvement in the shooting, while McRyan's people are willing to let a murder go unpunished in order to save face. Even the supposedly noble side combating the president sink into shadow tactics simply to avoid rocking the boat.

Thus, the film lacks even the sliver of hope found in the '70s anti-Nixon movies. Even the bleakest of those movies at least implied that getting a few bad eggs out of the system might right it, even if few of those films ended positively. De Palma grounds this movie in the '60s and '70s, but he lets the influence of Reagan seep into the movie, as if to say that a public that would elect such a figure so overwhelmingly was beyond hope and that nothing would ever fix the machine.

But he also situates Jack, and perhaps even himself, as a product of that machine, at least in terms of the conservative behavior even in these committed do-gooders. Accusations of misogyny have already cropped up in my research of the De Palma films I've seen, and I believe it only gets worse from here. The opening segment of Blow Out hedges too closely to that of Dressed to Kill for me to consider the similarities coincidence or even proof of the director's love of Psycho. Is this, then, De Palma's reckoning with the potential misogyny of his previous feature's opening rape fantasy, a point he underlines by cutting to the studio where two men lackadaisically criticize only the falseness of the woman's scream and not the horrid moral content of this sleazy tripe?

Jack suffers similarly: he becomes so immediately obsessed with the conspiracy that he tries to get Sally to listen to his recording of the event that almost killed her merely a day after they meet. She tries to skip town to avoid trouble, but Jack subtly keeps her from her train just because he needs her help, which he later demands in bullshit moral posturing over her profession. Throughout, he guilts her with reminders of saving her life. A romance develops between Jack and Sally, but it is undermined at all times by the man's exploitation of the woman, a twisted relationship that peaks in the savage, ingenious, heartrending conclusion, in which the abuse goes so far that Jack can now bring back the actual dying screams of a woman to put into the exploitation movie.

Technical (and technological) skill abounds in Blow Out. But De Palma is no longer simply reveling in the artifice of cinema but trying to find reality and a path to changing it through film. After making so many Brechtian films, only now does De Palma truly see the outer edges and limitations of the form. Many people, myself included, routinely argue against that most infuriating and meaningless of critical shorthands, "style over substance," is a weak criticism because style is substance. Blow Out plays as a demonstration of this fact, intricately detailing how the construction of a movie, not only in the ordering of scenes but in the balance of elements within each shot, gives the film content and meaning.

In a sense, this is the most mercilessly comic film De Palma's made to this point, a shaggy dog story leading up to a horrible, revolting punchline, but the sorrow rolling off the film stands in sharp relief to the more sardonic wit found in earlier movies. Obsession and The Fury already contained elements of a more human side to De Palma's postmodernism, but Blow Out emerges as a full-on example of tragic romanticism. Searing as that final shot of Travolta desperately plugging his ears is, just as memorable is the 360-degree dolly track around him and Sally a few minutes earlier, the slow motion taking the jubilant ecstasy out of the concluding circles of Obsession and leaving only heartbreak, the pain only emphasized by the mocking fireworks bursting overhead.

This incorporation and modification of De Palma's other work -- the autocritique of his comic breaking down of Dressed to Kill; the image-centric first-run of the film, Murder à la Mod, playing on Manny's TV; the despairing alteration of De Palma's giddiest moment to date from Obsession; and the broad inversion of his recurring voyeur motif from image to sound -- gives Blow Out a mature take on the director's love of reference. By not simply regurgitating his work but analyzing it and shifting the meanings of previous moments, De Palma finds a way to examine the nature of film without losing sight of his narrative. In fact, he enhances the movie, gives it contours that not only adds different interpretations to the film but deepens the impact of the main story. And I must say, however blunt some may find it, the ending hit me harder than Antonioni's chilled, meditative ambiguity ever will. This is a beautiful, thought-provoking film, and it's one of the finest movies ever made on the subject of film.