Madonna with the blue diadem – Raphael

Several years ago I visited the prints and drawings room at the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh and was treated to my own little exhibition starring a lovely Raphael drawing. While it’s nice to get close to such pictures, to take one’s time with them, to meet them as individuals, it is also extremely rewarding to get positively drunk on a rich and steady stream of Raphaels. An undeniable advantage of living in Vienna is that our galleries treat us to exhibitions that are far from modest; our ample imperial collections are embellished but hardly outshone by guest appearances from the Louvre and the National Gallery in London. Such frenzied visual gluttony leaves one with very different impressions of the overall trajectory of Raphael’s work than calm meditation on a single piece.

Allegorical figure of poetry – Raphael

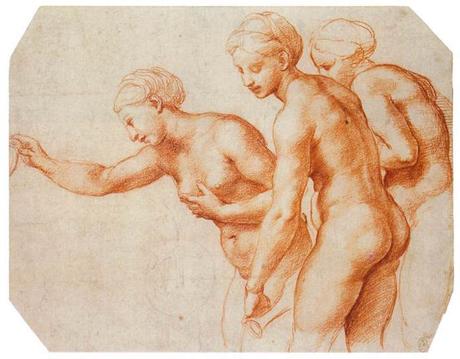

For one thing, it struck me how important tone is to his compositional strategy. Right from the early preparatory stages (and from his early years), his torsos and legs are offset simply and elegantly by plain slabs of tone. The effect is remarkably spatial: tone really does work, it is by no means a filler. One watches him carve an arched back deep into the picture by means of crude but deliberately-placed tonal contrast. In more complex drawings with many figures, this same simple strategy becomes meaningfully elaborate. Tone relates each figure to every other, especially in terms of depth. Plain, round heads and simple arcs of arms are woven in and out, set back at different distances, and curled gently towards us by rolling rhythms established largely tonally. Gently undulating movements ripple through tranquil and otherwise crisp, idealised figures. The masterful, airy sense of space informs us that we are emerging from the stilted Dark Ages into the spacious, glistening pastures of the Renaissance; it invites us to suck in a deep breath of that heady air.

Raphael

The force of this tonal organisation carries over into his painting, which is luminous. The brightness of his figures still gleam against the bright jewel-blue landscapes. Rather than dull them to grey, Raphael neutralises them with white, keeping their contrast limited but their color otherwise pure. Without invoking da Vinci’s atmospheric haze, Raphael offers us sharply-drawn cities that recede by fading to an icy blue; they retreat into the distance but glow as lavishly as the radiant figures.

It is a sheer delight to observe his methodical approach. Seemingly uninterested in the peculiarities of individuals, he treats them with egalitarian lines that harmonise their quirks into balanced lines and forms. Thus subdued, each ideal human becomes a conduit for graceful forces, and Raphael can make them dance, can animate these soft puppets with a living movement that courses through them with the steady and mesmerising will of flowing water. One observes again and again that he often draws whole scenes of nudes: thoroughly inappropriate nudes in solemn religious settings. Drawing is a tool of understanding, and Raphael acquaints himself with every aspect of his figures as he works variations of the picture.

Raphael

Alongside these careful nudes are painstaking drapery studies. A cloth hangs over a chair, as though it might be wrapped around a waist, and is reproduced faithful to life. Then it is redrawn, less stiff, with more emphasis given to the imagined meaty masses beneath. One sees immediately that he combines these two separate studies, these two firm foundations, into a meaningful amalgam of fabric and flesh–that each enhances the other, describes the other, that they move together. And his draperies are incomparably airy, infused with a lightness that only such sure knowledge of both figure and folds of cloth can achieve. The truly inspired pictures augment his understanding. Air blows up under garments and lifts them lightly, it teasingly curls their hems. The billowing, swelling folds extend the figures into otherworldly forms with a magical presence about them. What Raphael draws is too perfect to be real, and yet so natural as to seduce us into believing it anyway.

Raphael (print of a fresco)

Raphael’s drawing is perhaps most mesmerising for its delicacy. That simple chalk marks can produce such textural differences between skin and fabric is astounding. A supple arm or face can be as fine and smooth as porcelain, nestled into a rustling bed of hatching that describes those carefully-observed folds. There are some exquisite passages of hatching that run counter to the folds of the fabric, opening it out in a radiating fashion. Such control shows us where his attention lay, and while it might be far from the throbbing muscles of Michelangelo, or from the frenzied swirls of Leonardo, we appreciate that his own emphasis is equally compelling and equally distinct. Raphael delights us with a clarity that rings like crystal, with an enveloping vision of humanity that softens and perfects his figures into more noble and gracious manifestations thereof.

Raphael

Artists are often called upon to produce endless novelty, to demonstrate their ‘creativity’ by producing something entirely unexpected. Raphael’s tendency toward ideals or universals in his figures suggests a rather an urge to perfect each previous attempt, to take up the idea again and refine it. His inventiveness is the truly inquisitive kind that attends very carefully to its subject, seeking to extract the most pleasing and elegant and finally effortless solution that comes out of deep familiarity with that subject. This genuine inquisitiveness uncovers endless variety on a single theme, as is evident in his Marys. His parameters are tight–circular rhythms, pinks and blues, babies cradled in crescents of arms–but each new iteration probes the possibilities in a breathlessly fresh manner, the glowing and trembling air positively wet with dew.

Three graces – Raphael

The Albertina, swarming with visitors, gives one something else to reflect upon, which is the way people fear the art, and the way they talk about it. Whether a tour group or a pair of friends, two roles tend to emerge: one type stands helpless and intimidated before the Raphaels, the other speaks with authority. While one follows in silence, the other puts on her ‘tour voice,’ a dreadful monotone that indicates she doesn’t quite appreciate her listeners to be humans; or talks with adamant certainty about Raphael’s technical aims and his motivations as if they were solid facts. This last, particularly, strikes me: an appeal to the formal properties, but a very arrogant one that seems to impose more on the picture than it extracts from it. Or one overhears an appeal to formal properties that is infuriatingly empty: a teacher solemnly tells his students to come nearer to the drawings, and finally to ‘schauen Sie die Hände und die Füße an, wie die gezeichnet sind,’ (‘Look at the hands and feet, at how they are drawn,’) with no further comment, no indication of particularly successful or unsuccessful strategies, no disappointment that in these instances the hands are rather weakly drawn and clearly not the emphasis of these more compositionally-oriented drawings that incline rather more towards neglecting the details.

My humble artist companion and I enter the gallery with another attitude altogether. We come, admittedly, with our familiarity with certain Raphael paintings, of that single drawing (now on loan to the Albertina), filled with our predilection for Michelangelo, but with our eyes open, ready to greet the pictures as they are. Our conversation–sparse, because of our private absorption in the pictures–is quietly observational, relishing a confident mark, joying in vivid colours, delighting in the judicious variety of the mark-making, in an unexpected and strong row of square knuckles, but also regretting the careless sections, the limp passages that lack conviction. The longer we stay with the pictures and the more we think about his choices, we start to appreciate what makes Raphael distinctive, why Ingres would later strive after his elegant fastidiousness, how classical it feels, yet at the same time coloured with the jewel-like hues of the Middle Ages. We are always sharing, wondering, noticing. If these humble comments can give you some handle on Raphael, give you some way to think about the formal properties in a concrete way, open your eyes to the simple delight a picture can awaken in you, I sincerely hope they might bring you a step closer to genuine appreciation. For as Aristotle opens his Metaphysics: ‘By nature, all men long to know. An indication is their delight in the senses. For these, quite apart from their utility, are intrinsically delightful, and that through the eyes more than the others.’

Raphael

Aristotle. 2004. The Metaphysics. Trans. Hugh Lawson-Tancred. Penguin: London.