The perpetual moral free-fall of Breaking Bad should not be as sustainable as it's proven to be. By the start of its third season, which begins only with the show's 20th episode, Breaking Bad has already traveled such dark territory the question arises whether it can keep going before slipping into absurdity. However, the program already had a built-in black comedy that underscored its drama, and somehow the greatest show currently on television only gets better as things continue to spiral.

When last we left Walter White, he'd come into his own as a meth manufacturer in time for inconsistencies in his lies to pile up until Skyler's suspension of disbelief snapped. But nothing compared to the shambles of Jesse's life, which hit rock bottom in such horrific fashion the look on Aaron Paul's face communicated a total, instantaneous collapse. With both protagonists coming apart at the seams, the plane collision that ended the season almost seems an afterthought.

The fallout from that crash hangs over the first few episodes, but as Walt says in an awkward attempt to console a gym full of disconcerted students, people move on, and soon the terrifying ordeal of showering shrapnel and body parts fades into memory as characters continue to deal with their own problems and have no time for thoughts of dead strangers. Walt's too busy trying to get the cat back into the bag with Skyler, who reveals how easy the truth was to figure out once she looked into Walt's alibis. Jesse, meanwhile, is shocked into sobriety by Jane's overdose, left wracked with guilt and confusion as to how to proceed.

The third season is filled with climaxes, with a number of episodes so brilliant that distinguishing highlights nearly becomes a futile exercise. Besides, the true joy of Breaking Bad lies in charting the continual, brilliant growth of its characters, all of whom remain some of the most fascinating people on television. Supporting characters make more of an impression than the leads of most shows: Giancarlo Esposito refines his dapper, hidden-in-plain-sight dealer Gus, continuing to be both appealing as an alternative to the psychotic, using dealers who made Walt's early exploits so terrifying but also a shrewd, calculating monster with a much more sophisticated and unpredictable evil. Esposito finds a way to be unsettling even at his most disarming, his friendly smiles as "Chicken Man" Mr. Fring as disturbing at times as his cold, hardened stare.

As Skyler, Anna Gunn has thus far played the supportive but slowly suspecting wife, always trying to hold her family together as Walt's disease throws everyone into emotional turmoil and his frequent absences only exacerbate things. Finally aware of the truth, however, Skyler must contend with more than ever. Rightfully seeking to distance herself and her family from Walt and the inevitable repercussions of his new profession, Skyler must now deal with the bewildered and even hostile reaction from the rest of the family, who perceive her call for divorce as sudden and unwarranted. But of course, she can't reveal why she's leaving Walt, not unless she wants to implicate everyone and further rip everything apart. Gunn's performance, though hard-edged, is heartbreaking: she has a caged look on her face at the start of the season, seeking to keep Walt away even as he calls her bluffs with arrogant scorn. Her eventual resignation to her husband's return is one of the moral low points of the show, and also one that reveals the depths to which Walt has sunk.

Her seeming trip off the deep end adds strain to Hank and Marie's relationship, hitting a rough patch as Hank tries to deal with his PTSD from the El Paso incident. Hank, erstwhile the biggest caricature on the show, at last starts to feel human, softening his bluster with fear. His aggressive pursuit of "Heisenberg" morphs from a stalling tactic to stay away from El Paso into an outlet for his demons, and Dean Norris' broken, quiet admission "I'm not the man I thought I was" following a disgusting and brutal vent of his anxiety and rage is shattering in a way the gorilla-like oaf could never have been only a season ago.

Of course, the primary focus of the series remains on Walt and Jesse, who undergo such startling changes throughout this season that a lesser crew of writers would almost certainly fail to make these growths organic and believable. Cranston channels Walt's filial concern into villainy, turning the good intentions a man trying to leave something behind for his family when he dies into self-righteous outrage that Skyler would not understand, forgive and even laud the efforts he's gone to in order to provide a nest egg. Cranston never gives voice to the demons eating at him, only once verbally hinting at what's going on inside him when he speaks vaguely of having to live with what he's done to help his family. But his every look conveys pain; it's easy to forget what a funny man Bryan Cranston is, and a few flashbacks scattered across the season of his early marriage and professional life show a carefree, joyful Walt so disconnected from the tortured, angry man in the present that those flashbacks almost seem like behind the scenes footage of the actor and not the character.

At last, however, Aaron Paul eclipses his co-star. Sober, Jesse cannot retreat into his meth haze to avoid confronting his life, and it soon becomes apparent that sobriety does not bring clarity. Well, apparent to everyone but Jesse. Jesse's sober look reveals the past brilliance of both makeup and Paul's performance: he looks hale and fresh-faced where he used to constantly be disheveled and bewildered. But he's still the same dumb, stunted kid he always was, but now he deals with grief he does not dull, leading him to, if anything, even crazier actions. He and Walt spar over cooking at the start of the season, but when Walt goes to bat for him and brings him into Gus' high-tech operation, Jesse soon finds ways to push his luck, getting ideas about dealing under Gus' nose and looking to settle old scores despite the clear conflict this raises with the organization.

Yet Paul never plays, has never played, Jesse as nothing more than a hopeless, self-centered screw-up. More than ever, he serves as the show's fluctuating, self-defeating but always striving moral core. Jesse's sense of right and wrong is so skewed by everything around him that not even the blatant common sense of not rocking the boat with the organization can penetrate the passion with which he throws himself behind an idea when it breaks through the fog of ambiguity hanging around him and the show. This is a bravura performance, more heartbreaking than ever but also more tangible for breaking out of his addiction to find more pedestrian hells.

I said earlier that watching these characters grow existed outside episodic distinction, but I do want to highlight two episodes in particular. The first, "One Minute," brings together the threads of the first half of the season in such a way that things are left in more turmoil in their wake. Featuring amazing, terrifying work from Norris and a mounting sense of foreboding, "One Minute" offers one crushing line after another and the first of several "holy shit" climaxes of the season. The other noteworthy episode is "Fly," directed by Rian Johnson, stylish maker of the excellent Brick. Simply one of the finest, oddest bottle episodes in recent television, "Fly" is everything a bottle episode should be: absurd, claustrophobic, revealing, summarizing and forward-looking. The tension of a sleep-deprived Walt dancing around his culpability in Jane's death is maddening, while the insane humor of his single-minded need to kill a fly in the meth lab offers all the mad comedy one expects from a location-limiting plot.

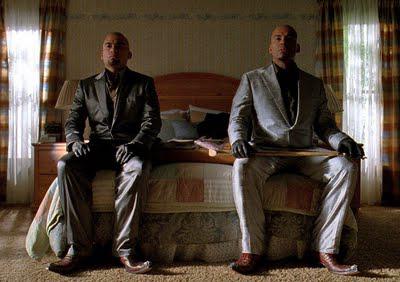

The little touches that make "Fly" such a delight reflect the intriguing minutiae of the series as a whole. I like that Walter Jr. is played by an actor who actually has cerebral palsy, as it allows everyone to mess with television conventions concerning the disabled by giving RJ Mitte the opportunity to sarcastically undercut every "I struggle every day so what's your excuse?" sermon given to various characters down in the dumps. The devilish grin on Mitte's face when he does so has an element of catharsis to it, a delight in skewering the role he and other disabled people have to watch able-bodied people romanticize. Bob Odenkirk continues to delight as the capable yet dopey lawyer Saul Goodman, his performance two-dimensional but so perfectly played you don't even need growth. Saul's money laundering schemes are farcical, but watching Odenkirk try to seriously pitch Walt on "investing" in laser tag is a riot; even Skyler can't bring herself to let this idiot handle the money she despises. There's also the recurring sight of Tuco's cousins, taciturn hitmen moving with methodical, unyielding carnage as they hunt down their relative's killer. Like many things in Breaking Bad, they're ridiculous, but they fit uncomfortably well within the wild world the show has conjured up out in the hot, noxious cloud of drug-ravaged Albuquerque.

When Walt started using the alias "Heisenberg," he slyly brought up the name of the scientist renowned for the principle that nothing under observation can be viewed truly as it is. As the show progresses, we see this principle effected in Walt: he thought he could just make enough meth to provide for his family, but the game shifted around his product, and now he's radically changed himself. Breaking Bad is like the expected rainstorm that arrives after someone rhetorically asks, "How could it get any worse?" Things always get worse in this show, but never just to be dramatic. Every lurch, no matter how sudden or off-balancing, is earned, and the show's third season marks yet more improvement for a show that, like The Wire before it, seems more and more a timeless classic even as it still airs.