Gerald Thomas at Livraria Cultura

Gerald Thomas at Livraria CulturaTrying to explain one’s motivation and art, while defending an individualistic view of the same, can be a time-consuming impediment to progress for any professional artist, as it surely must be for most people inside or outside the public domain.

But to say that Gerald Thomas, the talented director, writer, producer, illustrator, and graphic designer, has a particularly “individualistic” point of view is clearly an understatement: he is absolutely, without hesitation, Brazil’s most controversial contemporary stage figure to date.

His copious plays and uniquely identifiable theater pieces, along with an impressive and ever-expanding body of operatic work — not to mention his London Dry Opera Company and previous collaborations with composer Philip Glass — have enlivened the dramatic and performing arts to no end (See the following link: http://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2012/09/10/getting-to-the-bottom-of-gerald-thomas/).

With constant “exposure” of his avant-garde ideas in the press and in the theater, however, Thomas has been forced at times into expressing his own level of frustration at audiences in no uncertain terms, as evidenced by his much-ballyhooed butt-baring episode at Rio’s Teatro Municipal, back in August 2003 — an episode that elicited an enormous amount of media coverage.

Residing in London for most of the remainder of that year, he returned to New York in March 2004 for the opening of his play Anchorpectoris (The United States of the Mind) at La MaMa Experimental Theater, on E. Fourth Street in Greenwich Village — the scene of his first stage triumphs with ex-mentor, the late Ellen Stewart, and the works of Irish playwright Samuel Beckett.

In this interview, originally completed in the U.S. in December 2005, shortly after the successful Brazilian run of his Um Circo de Rins e Fígados (“A Circus of Kidneys and Livers”) with actor Marco Nanini, and updated during parts of 2008-2009, Gerald quite candidly delved into, and expanded upon, a wide range of topics, including his early career as an illustrator and in the opera house; his major artistic and literary influences; his personal recollections of John Lennon’s death and 9/11; his criticism of Brazil’s former Minister of Culture, Gilberto Gil; and his future plans, among which were his long-awaited, stage-acting and directorial film debuts, as well as the release of his book, Suicide Note.

Politics mingled with art — ah, there’s the Thomas rub! And if ever there were an example of the two intertwining and becoming indisputably one, then Gerald Thomas — an individual whose palm print can be found on every facet of the performing arts — would be held up as the premier exponent, Brazil’s poster-boy for artistic and political activism, and a true, modern-age Renaissance man for the new millennium.

Josmar Lopes—The first thing I’d like to know more about, as I’m sure our readers would, too, is the origin of your name: is it really Gerald Thomas?

Gerald Thomas—It’s my first and middle name. The full name is Gerald Thomas Sievers.

J.L.—Have you had any identity crises or cultural clashes because of your American-sounding moniker?

G.T.—I’ve always been a “Nowhere Man” or, when I was a kid in school, a “Nowhere Boy.” I came to realize that very soon, because I never, ever fitted in. I was always from “abroad,” from “another culture.” At home, we never ate what the people of the country we lived in ate and that made me feel terrible. I remember the very first time I was invited (by the neighbors on the ground floor in Leblon, Rio) to come and eat dinner with them. I was stunned at the amount, the variety of different foods on the table, amongst which [were] black beans. We had been in Rio for about a year and all I knew was boiled potatoes and meat of some sort or another. Suddenly, this colorful rainbow opens up and I felt so great about Brazil.

J.L.—You learned recently that you were born in New York City but moved to Rio at an early age. Despite most articles claiming you were from Brazil, how has living in places like the Big Apple, Rio de Janeiro, and London contributed to a better or worse sense of your own individual identity?

G.T.—In Brazil, I have to say that I was born there, given the nature of my criticism of the government and Gilberto Gil, the minister of himself. No foreigner would ever be able to say such things without being thrown overboard. But a real and intriguing question does exist about the place where I was born: I do have three birth certificates and I do carry a German passport. It’s weird in a way to feel as though you belong to all of those places and, yet, the only place I can really call home are a couple of blocks on the East Side of Manhattan, between St Mark’s Place and E. Third Street on Second Avenue. I guess my parents must have registered me every time my father was moved by Lloyd’s Insurance from one country to another. That may have been a smart move.

J.L.—Indeed it was. But have you ever experienced a feeling of loss when you go abroad because of your country of origin or your Jewish background, in view of the apparent pride you have in being Brazilian?

G.T.—I know that the Jewish thing should play an enormous role here…but it doesn’t really. I guarantee you that I would be a rich man now if I had played that card but reality has it that I never felt very comfortable with those rituals. My bar mitzvah was awkward, I felt terribly awkward, having to memorize all that stuff phonetically. Plus the “father that brought me up” wasn’t Jewish himself and, during the years as a volunteer at Amnesty International in London, I got to know a lot of Catholic priests who were protecting political prisoners in Brazil. I thought that those people were so great. They showed me Italy for the first time. It was through their eyes that I saw the Vatican, its little holes and labyrinths…

J.L.—It’s a fascinating place. Since then, you’ve been all over the world, practically, and you’re always on the move. Are you comfortable with the ever-increasing globetrotting demands of your career?

G.T.—Always less comfortable because traveling nowadays is a problem, it consumes far more energy out of you with all the “checkpoints,” and cities are growing out of control, making traffic impossible, irritatingly so. I used to be productive in planes: open up the laptop and work. Nowadays, the guy sitting next to me in business class is just concerned with getting drunk. So no, thanks. I’m not going to wait until his margarita spills all over my PC.

J.L.—I don’t blame you. In contrast, throughout his life composer Richard Wagner was often referred to as a man “possessed.” Are you similarly possessed, and by what?

G.T.—I try to stay away from things like that. And as for what’s written about “mythological” characters, one never knows. Was it really so? Some people are furious, some are angry, others are simply frustrated and have tantrums and History can turn all that into “being possessed.” I am as cool as can be because when I have dealt with the actors, I remain in the theater and deal with all the other technical aspects of the play or opera I’m staging.

J.L.—That’s probably the best approach. With opera being such an international endeavor, how many languages are you fluent in?

G.T.—I really only speak three languages: English, Portuguese and German. The rest is parroting my way around the world.

J.L.—Yet you speak with a slight British accent. Would it have been more difficult for you career-wise if your name had been Caetano or Chico and you had spoken with a Brazilian accent? Or spoke no English at all?

G.T.—Well, that is difficult to answer since there are thousands of British or American or Australian or Canadian directors in the world who’ve achieved nothing in spite of their well-spoken English. I think that I owe my position in the world to my talent. Bluntly speaking, that’s it.

J.L.—I agree. Speaking of talent, who was the person or persons whose views influenced you the most as a youth?

G.T.—Samuel Beckett and Caetano Veloso, Hélio Oiticica and Haroldo de Campos. Marcel Duchamp, Marcel Duchamp and Marcel Duchamp. Saul Steinberg, Steinberg and Steinberg.

J.L.—That’s quite an impressive list. Where did opera first come in to play and how did you eventually come to stage it?

G.T.—That was in 1987 in Rio, and The Flying Dutchman was the victim. A very conceptual piece to begin with, I decided to stage it in such a way that the place was Berlin, East and West, divided by the Wall. The dead man (the Dutchman) and his vessel would appear on the East Side, and Senta would be waiting for him on one of those wooden platforms built by the Allies, forced to look over onto the other side. But all of that was metalanguage, since it all played as an installation watched by a “false” audience inside a mega-exhibition hall: the Kassel Documenta. So, two years before the fall of the Wall, it had already become an “installation of the past, an artwork worth nothing compared to the thousands dead trying to cross it.”

J.L.—Have your musical and operatic tastes subsequently evolved over the years?

G.T.—Yes and no: I have gone back and decided on opposite extremes such as Mahler and Schoenberg. I could sit all day and just vary between recordings of their works…

J.L.—You seem to show a strong affinity for “modern” music, i.e., Arnold Schoenberg, Philip Glass, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Ferruccio Busoni, and others, which you’ve used frequently in your pieces. Is there a specific reason for this?

G.T.—But I also steal from Wagner and from Mendelssohn and from Haydn. There isn’t a specific choice for the moderns, though it gives me pleasure to work with someone who is alive and well, rather than some corpse.

J.L.—Have you ever used or thought of using Brazilian classical or popular music in any of your works?

G.T.—Other than Villa-Lobos, I know very little about Brazilian classical music. I do know how to drum the samba, since I am one of a very few allowed into Mangueira to be part of the drum section of their victorious samba school.

J.L.—Then you must know Marisa Monte, whose father was connected at one time to Velha Guarda (“The Old Guard”) da Portela Samba School in Rio?

G.T.—I was an “adviser” to her, when she first put her legs and voice on stage, through the hands of Nelson Motta: that was in 1986.

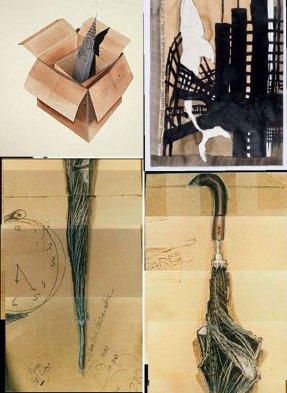

J.L.—You started out as a graphic artist and illustrator—a very good one, I might add. How has this early background in art and design bolstered your work on the stage?

G.T.—At age fourteen I managed to creep my way into the rehearsals of Victor Garcia’s version of Genet’s The Balcony in São Paulo. Undoubtedly one of the greatest stagings of the twentieth century, this vertical production not only caused a hell of an impression on me, but I also learned a great deal about the theater while being there, every day (and night, ALL night!!!). I learned what “modern and experimental theater” was and how that somehow integrated with the visual arts. In other words, I was experiencing a live Bosch painting, as it were. Then, two years later, in London, I sort of “infiltrated” the Royal Shakespeare Company while Peter Brook was rehearsing his Midsummer Night’s Dream. So, all the visual arts and dramatic arts came together as a whole.

J.L.—You once worked at The New York Times, The Boston Globe, and other newspapers. Do you still find time to illustrate for publications that are outside your normal field?

G.T.—No fun no more! I illustrate the programs of my own plays and the posters and I “design” or draw each and every one of the scenes that are to be staged…but that’s about it as far as drawing is concerned, commercially. I have a lot of recent material, but I keep all that to myself. Who knows… one day there will be an exhibition?

J.L.—Most recently, you’ve designed the posters and programs for Um Circo de Rins e Fígados (“A Circus of Kidneys and Livers”), starring Marco Nanini and staged at Teatro SESC in Vila Mariana, São Paulo.

G.T.—Yes, I’m involved in every single aspect of the theater, even in the soundtrack. Too involved!!! Some call me obsessed but I just find it normal since it’s an object of my creation and nobody else knows exactly what’s going on in this head of mine. So, instead of spending hours explaining, I might as well just do it myself.

J.L.—Do you prefer doing it all yourself, or do you leave certain tasks to others?

G.T.—Well, let’s say I delegate a little.

J.L.—Is this a form of “control” over the creative process?

G.T.—Look: we play being God! So, in the black box we can control the temperature, the smoke, the lights, the volume, the exactness of everything. That’s why I am present as much as I can at every performance. I have a little corner where I hide and even communicate with the players and gesture to them frantically, according to how the performance is going that night. Since I give all the cues, I can change things on the spot. I tell the actors in a clear voice that they can understand (when the PA system is loud enough) and, there it is: a brand new scene, created on the spot, on that very night for that specific audience, depending if there was some MAJOR news that day.

J.L.—Moving on to Brazilian pop music, bossa nova, seventies rock and Tropicália, were you attracted to any one style over another?

G.T.—I was very involved with the Tropicalistas. Still think that this was one of the most innovative movements ever! On the other hand, I was going to The Royal Albert Hall to some classical symphony, or to Berlin to watch Herbert von Karajan, or to see and listen to Jimi Hendrix or Led Zeppelin here at the Filmore or at the Earl’s Court Arena.

J.L.—Do you still enjoy the music of Jimi Hendrix? The Beatles? John Lennon?

G.T.—I progressed as times progressed. I loved Nirvana and Pearl Jam and so many new bands out there that this interview would become as long as the Yellow Pages. But I still go back to the old icons, sure!

J.L.—You do resemble Lennon, you know, especially in your earliest photographs. You once portrayed him on the stage, did you not?

G.T.—Yes, that was meant to be a joke. Os Reis do Ié Ié Ié (“A Hard Day’s Night”) was the reunion of the Dry Opera Company and it was to have had only TWO performances. But you know how things go. Offers come in and the whores that we are…we end up accepting them!

J.L.—You posted a poignant remembrance of the twenty-fifth anniversary of his death on your blog, http://www.geraldthomasblog.wordpress.com. Do you remember the shooting?

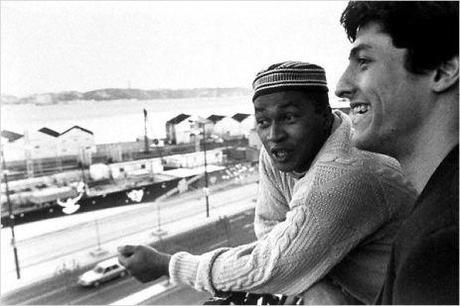

G.T.—As if it were yesterday! It was a spooky day for me, because it so happens that I had brought a former political prisoner from Brazil, a poet himself—Alex Polari de Alverga and wife—and all he wanted was to be photographed in front of the Dakota building. So, that’s what we did that day. Almost all afternoon we were there, outside Lennon’s door. Little did I know what was to follow: When I dropped the couple off at an apartment that I was vacating and driving myself to my new Village loft, I heard Scot Muny come to the microphone and make the announcement. Unbelievable. I rushed over to the Upper West Side (out of instinct, I don’t know…) and found a bunch of people there in tears…

J.L.—You were an eyewitness to 9/11, and from your apartment window, if I’m not mistaken. How did that terrible event affect you personally?

G.T.—I am not the same any more. I’m on medication. I lost friends. Witnessing what I did, as did millions of other New Yorkers… it changed my life, Joe. It changed the world…Sometimes I’m up at night rethinking the entire scene, over and over and over and over…

J.L.—How did these feelings about 9/11 compare to what you felt after Lennon’s untimely end?

G.T.—If the “dream was ever over,” it is NOW.

J.L.—Have these two tragedies soured you on living in large cities?

G.T.—Which two tragedies do you mean, 9/11 and Lennon? I wouldn’t even begin to compare… Terrorism is something so abominable and incomparable to individual murder by a crazy lunatic!

J.L.—Let’s talk about literature and poetry, something that has occupied you personally and professionally for the better part of forty years. When did you first learn about concrete poetry and the de Campos brothers?

G.T.—I was fourteen years old, living here in NYC with Hélio Oiticica, and he wouldn’t stop talking about the de Campos brothers. And he had some of their early works. So, I picked up whatever I could and started to read them, or leaf through those “pages.” I was fascinated, as you can imagine, because there I saw a mixture of words and images, almost something in 3-D, touchable and so “lucid,” inexplicably so. Words meaning others and it came to my perception that early on there was this “thing” called metalanguage. I was addicted at that age. Have been since.

J.L.—What other literary figures impressed you the most as an artist?

G.T.—Oh, there is Beckett—which also later developed into a personal relationship lasting until his death—James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, Joseph Conrad, Hegel, Kafka, Kafka, Kafka, and the Greeks, and as I sat in the British Museum Reading Room doing my studies, so many authors came across my eyes: it would be silly to name all of them. It would also trivialize them. But there was this one William Shakespeare who still hasn’t left me and I am not intending to leave him either.

J.L.—You’ve presented numerous works by your close friend Mr. Beckett, along with Shakespeare, Brecht, Kafka, Heiner Müller, and others. What contributions have they made toward the overall formation of your art?

G.T.—No, I’ve never done Brecht (not that I can remember), but I have been a guest of the Berliner Ensemble, during the days when Berlin was still divided by the Wall. Well, all of those playwrights are—combined—part of what I am. If put together, vertically and horizontally, with what I have lived through empirically, the stories I was brought up with (the Holocaust) and the theater I built into my wardrobe as a child in order to “be somewhere”… what I’m trying to say is that ALL of which I have read and seen (and still do) causes an enormous impression on me.

That’s why I still don’t know exactly what to make of 9/11 and seeing the World Trade Center being hit. Being that the WTC were the towers of my generation: except for the Citicorp building, the rest of NYC was all built. I saw those two faceless monsters going up: they were the Warhol buildings (multiplications) or the Godot buildings: “nothing in two acts,” as Walter Kerr once described it in The New York Times. He later resigned, this critic that is, because he realized that Waiting for Godot was indeed THE masterpiece of the twentieth century and he didn’t have perception then, in the fifties. He said goodbye to his readers by saying that he must have ruined hundreds of lives of talented authors and actors and the like.

J.L.—You’re a prolific writer yourself, as well as a playwright and journalist, having contributed a number of articles to Folha de S. Paulo, Jornal do Brasil, O Globo, and other publications. Have you ever considered giving up show business for a career as a critic or political commentator?

G.T.—Never! I keep a journal. This journal is, finally, going to be published next year. The title is Suicide Note. I was offered a column in the most prestigious page in the most prestigious paper in the world (just guess), but in order to do that, I would have to give everything else up. I would have to be a “political traveler.” As much exposure as that would give me and throw me right into the limelight of mainstream AmeriKa, I declined because I cannot justify breathing on this planet without the theater or the opera. So, I will continue doing my work and other people, such as Wladimir Krisinsky, David George, Haroldo de Campos, Flora Süssekind, and so many others, will contribute with their opinion. Um Encenador de Si Mesmo (“The Staging of the Self”) is a compilation of such texts.

J.L.—Your stage productions bear the hallmarks of silent cinema, German Expressionism, Surrealism, Dadaism, film noir, and Theater of the Absurd—have I left anything out?

G.T.—Yes. You’ve left “me” out.

J.L.—I stand corrected! In fact, you’ve peeled away most theatrical elements down to their barest essentials—that is, little or no dialogue, stylized acting, non-specific sets, and dramatic, sophisticated lighting. Is this what you’ve tried to accomplish with your Dry Opera Company?

G.T.—No, that is because I’ve chosen such scenes to go on a tape to travel commercially around the world. I chose precisely the most viable scenes to go on such a tape: but if you saw the pieces in their entirety, you’d see a lot (and some people actually have complained in the eighties that there was “verbal hemorrhage”) of text in those plays.

J.L.—A while back, a New York Times piece hinted at your early fascination with light and shadow—and there’s certainly no shortage of light, shadow, and smoke on display throughout most of your works. Are you still as captivated by these effects as you once were, or have you moved beyond this aspect of your art to other things?

G.T.—I think that, like everyone else, I go through phases. This latest play, A Circus of Kidneys and Livers, has very little of those: it’s basically the text and the actors that matter.

J.L.—Good point. That said, Orson Welles was once described as the “boy wonder” of the stage, a master at multitasking who could act, write, paint, design, produce, direct, market, and promote his works—all at the same time. As formidably talented as he undoubtedly was, Welles spent his entire life actively selling the myth of his supposed “genius” to all comers. Would you categorize yourself as a genius in the Welles mold, i.e., someone who writes, directs, produces, markets, promotes, illustrates, and innovates, with the same non-stop intensity as he showed in his youth?

G.T.—No, but I fake it just as he—later in life—claimed he did. F for Fake is a great film. I would throw rotten eggs at any artist who would consider himself a genius! Seriously! At this day and age, after deconstructivism, iconoclasty… genius? Give me a break!

J.L.—Besides physically, what characteristics differentiate you from a Welles?

G.T.—Well, if I had accomplished Citizen Kane at age twenty-five, I would seriously give myself up as satisfied. It’s one of the best movies ever, EVER made. I’ve never thought of myself as anything close to Welles. In fact, while he was still alive, I almost came close to inviting him to play Hamm, in Beckett’s Endgame. That was right after directing the legendary Julian Beck, who died while we were touring with The Beckett Trilogy, 1985.

J.L.—Many felt that Welles peaked early on and never recaptured the inspiration he initially showed with his classic Citizen Kane. You’re 55 now—that’s more than twice Welles’ age at the height of his fame—and you’ve accomplished so much more in the theater than he ever did. What would you still like to do that you haven’t done as yet, theatrically?

G.T.—You must be joking! Welles was truly an INTERNATIONAL CELEB, and with clout. Whether what he did or didn’t do in the theater was good or not, I don’t know. The photos make things look rather kitsch. People who have seen it and described it to me say that it stank! But who am I to judge? Look at where the boundaries of my work stop and look at Welles!!!!!! My obit will be one paragraph long (if that!), while his…

J.L.—Your most favorable reviews have been for works that thrive on controversial subjects. Do you identify personally with the struggles of the protagonists of Moses und Aron, Doktor Faust, Tristan und Isolde, and Don Giovanni?

G.T.—I actually do. Moses especially, with the stuttering problem. And with the fact that it was a “spoken/notated” part, especially difficult to memorize for a player, when the entire orchestra is blasting notes of a completely different nature. Plus, that biblical subject matter does interest me very much—always has—so… Schoenberg’s life itself has always interested me, or, rather, fascinated me. So, putting it all together: Busoni and Schoenberg go hand-in-hand; Faust by Goethe is my favorite book (and until this date I have not entirely deciphered it, either in German or in English, or in Haroldo de Campos’s version: Deus e o Diabo na Terra de Fausto—“God and the Devil in the Land of Faust”). There you have the perfect subjects for me to delve into the darkest areas of the humanities, so to speak.

J.L.—You changed Faust’s profession from alchemist to artist—a painter, to be exact. Was this a conscious choice on your part, a sort of autobiographical statement?

G.T.—Certainly autobiographical…

J.L.—Were you deliberately placing yourself into the stage action and are you a frustrated actor at heart?

G.T.—Not anymore! I premiere, as an actor, next April 2006, in Asfaltaram o Beijo (“A Kiss Cemented Over”), an homage I pay to Beckett and the years we spent meeting in Paris.

J.L.—Do you regard yourself as more of an individualist and outsider, much in the manner of a Moses or a Faust?

G.T.—A total outsider, always. I was talking to Philip Glass just now and was telling him about the success Circus had, and how one has to constantly renew this pact with the world “within”, with the audience and with the press…It’s as if the world were a big memory bank that, given a month or two of our absence, would forget us altogether.

J.L.—Have you thought about tackling other characters of this type, for example, Britten’s Peter Grimes, Wagner’s Tannhäuser, or Berg’s Wozzeck?

G.T.—I am ready for all three of them.

J.L.—Aren’t you really more like Moses’ brother, Aron, a sort of manipulator of language and the spoken word?

G.T.—The image of me in the press certainly may appear so. But that has to do with the fact that the press is lazy. I ask you: how can any one person manipulate the press? How do you do that? With money? Drugs? Chocolate? Sex? How exactly? What does that phrase mean? As in a previous answer, I am timid and profoundly involved with sensitive questions about the nature of who we are. I am also very traumatized about the nature of who we are and what we are capable of doing. Aron wasn’t concerned with any of that: he merely wanted to sell his golden calf.

J.L.—Nothing you’ve done on the stage could possibly be construed as being a part of the mainstream. Has this “inaccessibility” to the general public, as it were, bothered you in any way?

G.T.—Sometimes the media builds this image out of nothing, just as it always has throughout History with not-so-easily-consumable-artists. But when some audience member walks in openhearted, he/she will find that my work isn’t all that inaccessible after all.

J.L.—Wouldn’t you prefer to be less on the cutting-edge and enjoy rather more widespread critical success?

G.T.—I’ve been given all the awards there were. The Molières and the (forget the names, really). I dropped the last Molière just to show the audience in Paris that it was made of chalk and not marble, and said quite bluntly that I hated to be endorsed by the middle classes. Those awards are given out by critics. I have no complaints, except for financial ones.

J.L.—In your opinion, is the notoriety you’ve obtained the best measure of triumph in your case, or are there other modes of measurements?

G.T.—I think that everyone who earns a certain amount of notoriety does so because of a number of factors: the media construct its own circus and make you into a “complex” and complicated “personality” (o polêmico) and the rest, of course, has to do with the work, with the fact that I am, in a way, untouchable, because I work in so many countries and have the endorsement of the top critics and the top houses in the world.

J.L.—Your frustration did manifest itself strongly at Rio’s Teatro Municipal in 2003, where you bared your buttocks after being roundly booed for Tristan und Isolde. Would you care to elaborate on what led to that encounter?

G.T.—I had received news that Haroldo de Campos had died just before the opening. That had already left me in a state. The boos don’t bother me. They actually amuse me. You can see that in the tape I sent you where I deliberately include minutes of it, as I enter the stage, during the curtain call after Flying Dutchman. But when I hear a rehearsed chorus from the first few rows, “Judeuzinho, volta pro campo!” (“Little Jew boy, go back to the concentration camp”), that… made my blood pressure rise up and… I lost it. It took me a year to get acquitted, and in Brasília, by the Supreme Court!

J.L.—Did the ruckus have anything to do with the appearance of a third major character introduced by you into the drama, namely Dr. Sigmund Freud?

G.T.—Absolutely yes! And the fact that I used cocaine as an analogy for the love/death potion given by Brangäne to Isolde. A mess from the start. Pressure from the start because the artistic director of the Teatro Municipal knew my concept an entire month before I left London, since I had published it in my column, at the time, in the now nearly defunct Jornal do Brasil.

J.L.—That was quite an unusual touch, wouldn’t you say, to have the title characters analyzed by modern history’s most famous shrink?

G.T.—That’s my job! Otherwise, just have the conductor stage the damned thing, as Karajan did so many times. Why call me? To sell tickets and fill the house. The Municipal has never been so sold out EVER!!!!!

J.L.—Do you find Brazilian audiences are less tolerant of these sorts of novelties than other audiences are, say, the Americans or the Europeans?

G.T.—No, they’re just as open minded. But not when it comes to Richard Wagner! Man! Wagner is stronger in Brazil than anywhere else… I mean, the traditionalists. But on the following nights we saw none of those problems. And may I point out that the troublemakers were just a handful within two thousand five hundred well behaved, opera-lovin’ people.

J.L.—But do think about staging Wozzeck one day—hopefully sooner than later. I had a brainstorm while listening to the Saturday afternoon Metropolitan Opera broadcast wherein I imagined the whole thing set at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, with the title character a U.S. Army soldier just returned from Iraq; haunted by visions of prisoner abuse at Abu Gharaib; then acting out his delusions by killing his live-in girlfriend—it has your signature all over it!

G.T.—What a great idea!!!!!! But which opera house would invite me to do such thing? As far as I’m concerned, I’m standing in line already! But where, and when? That’s the problem: like with anything else in today’s world, the titles offered to me are either totally unknown avant-garde or the very well-known and overdone pieces.

J.L.—What are your views on the current state of classical music and opera in Brazil?

G.T.—You know as well as I do that Brazil moves in waves and nothing lasts. Some say this is a good thing, some say it’s bad. It’s certainly the opposite of Europe and their secular cultural struggles, which never seem to end. It’s still the eternal anti-Schiller play and so on, or the latest version of the “anti-Hamlet” for the hundredth time. So, Brazil is very creative since this lack of tradition liberates its artists from this heavy commitment to battle these ghosts. Yet, I find that this also leaves an incredible emptiness which leads to the popularity of the soap opera culture (novelas) and the overwhelming LOVE Brazil has with television, more so than the U.S. (I find). So, as for your question, classical music and opera haven’t made a mark in Brazil because year in, year out there will be a Sala São Paulo, for instance, with heavy emphasis on classical programming—which is fantastic. But will it last past this current mayor? Or the next?

J.L.—What can be done to improve the unfortunately low expectations for classical artists and the performing arts there?

G.T.—Famine and poverty are the first priorities. To hell with the arts!

J.L.—Has the Ministry of Culture done much in the past few years to give aid and comfort to the arts?

G.T.—Gilberto Gil has certainly done a lot for himself! He is the Minister of Himself, and the ministry is called the “Ministério Gilberto Gil de Morte à Cultura” (The Gilberto Gil Ministry of Death to Culture). His fees for performing around the world have tripled and he simply loves to travel with Lula and shake hands with heads of state worldwide. It’s a scandal, it’s a shame and, yet, nobody says anything about it because the PT (Partido dos Trabalhadores—Workers’ Party) is a true Stalinist revengeful party and it wouldn’t amaze me if, soon, there were a blacklist: something equivalent to the McCarthy era here, except in reverse. Dreadful!

J.L.—What are some of your future plans with respect to opera? Is there anything you can talk about openly?

G.T.—I’m involved in certain German operas at this moment that are almost embarrassing to mention: I call them train station noise (at 5 a.m., when the trains are pulling in) but I have to direct these so-called “avant-garde” things because they pay and they pay well. There is also an opera “in development” with Philip Glass, which is based on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, and Bayreuth says it wants me in about one hundred years from now.

J.L.—This latest Thomas-Glass collaboration is exciting news for fans. In the past, many theater and film directors often ventured into opera. There was a time when Luchino Visconti, Franco Zeffirelli, Alfred Lunt, and Margaret Webster were all actively involved with its staging. This trend has returned somewhat with the operatic participation of Werner Herzog, John Schlesinger, William Friedkin, the late Anthony Minghella, and even Woody Allen. Do film directors have a better “eye” for stage detail than, say, the average opera or theater director has?

G.T.—I usually find that film directors are a total flop on the stage: here are two completely different languages. You might as well call a bricklayer to do the job! People are under the impression that “performing art” is one and the same. That is the biggest and dirtiest mistake ever. Imagine if you were to call Picasso to retouch or restore the Sistine Chapel, or Francis Bacon, for that matter. Michelangelo and the two I’ve mentioned are all involved in the “painting” media, but sectors are not to be confused.

J.L.—Have you given any thought to directing your own movies?

G.T.—Yes, I begin shooting Ghost Writer in about a year from now. I’m still developing the screenplay.

J.L.—What else would you like to direct, if given the chance?

G.T.—I’m an obsessive writer, so I’ll just continue to write my pieces. I think that History needs to move forward and we need to tell the stories of the times we live in, in whatever way we can. If we just keep on re-staging The Seagull over and over and over, or the classics, we won’t be telling people five hundred years years from now what the twenty-first century was about.

J.L.—That’s so true. By the way, do you have many friends or acquaintances in the movie business?

G.T.—Yes, I’m very close to Hugh Hudson, who directed Chariots of Fire, amongst other wonderful films, such as American Revolution; and Cacá Diegues, the Brazilian filmmaker.

J.L.—You made a cameo appearance in the film Terra Estrangeira (Foreign Land) by Brazilian director Walter Salles Jr. (Central do Brasil, Dark Water). How did it feel to be directed by someone else instead of your doing the job yourself?

G.T.—Oh, please don’t remind me of that. If I could…if I had the money I’d buy those frames and cut myself out of that movie…I wasn’t directed. Someone just said “roll” and there I was.

J.L.—You’re probably the most well-known, most talked about, and most written about Brazilian stage personality on the world scene today. How do you feel about that lofty position?

G.T.—I am very lonely and suffer just like anybody else when I turn on the news. Frustration kicks in, just like with anybody else. I don’t feel special, in fact, I don’t feel anything: all [that] I’ve done, I feel, has somehow been reduced to ashes. Don’t ask me why or how. It’s just a holocaustic feeling but, all the same, true. It’s vapor, it weighs nothing. I must reinvent myself, especially in this current world of NO values, of information overload, of shopping malls, of super-consumerism, iPods, internet, where people don’t really learn (they just copy and paste or use it for chats). This globalization has flattened Columbus’ world. It’s one with no memory or a weak one: it’s drugged, drunk, money-driven or driven by one god against another. We’re back to the Middle Ages, except that we have modern tools. It’s a horrible place where my profession doesn’t exist, really. So, all that I read about myself—I feel—I’m reading about someone who doesn’t exist; i.e., someone else or a ghost: a GHOST WRITER.

J.L.—I sense the theme of your screenplay at work. Can you give me some clues as to the movie’s plot and how it’s been coming along?

G.T.—What can I tell you about it, really, other than sending you bits and pieces of scenes or sequences, or scenes from my book (not yet published) by the same name on which this crazy pumpkin is based? Strangely enough, it is coming along: we’ve got money from the Independent Brits and the Danish (formerly known as) Dogma—they grew up seeing my plays all through the nineties when I started performing in Copenhagen: 1991 to be exact. We have DEUTSCHES money and we really don’t need that much more, or else I’ll start getting nervous about having to make a “hit,” when all I want is just to be able to experiment with the raw material and a funky story, surreal as hell, where the actual event always seems like dejà vu because, indeed, it IS being written by a Ghost Writer (unlike The Truman Show). This is an Arab/Western conflict which takes us back to ancient visions of Europe and the Founding Fathers of America. And Jihad. And the war of the Gods.

J.L.—Wow! I’m intrigued. What about the cast—any word yet on that?

G.T.—We’re casting in Turkey for a youngish Arab-looking boy, a teenager (same characters) and an older Arab man. There will be lesser or maybe even bigger names. I really don’t know… I will be one of the cameramen, but obviously not the cinematographer. They’re talking about some Italian (highly praised and awarded) and [paraphrasing Glauber Rocha’s famous statement about Cinema Novo] ALL I WANT “É UMA CAMARA NA MÃO E UMA IDÉIA NA CABEÇA” PORRA! [“…IS A CAMERA IN HAND AND AN IDEA IN THE HEAD,” DAMN IT!]

J.L.—Has the constant exposure in the press hampered you to any degree? You don’t seem intimidated or ambivalent by all the attention. How do you maintain your composure as well as your personal privacy?

G.T.—It’s impossible to have privacy when you’re having dinner and people are coming up to you constantly wanting to take a snapshot of you (with them, preferably).

J.L.—Thank you so much, Gerald, for your openness about yourself and your art.

G.T.—Thank you, Joe. ☼

Copyright © 2014 by Josmar F. Lopes