Out of all the stars labeled Box Office Poison by the Independent Theater Owners Association in 1938, Katharine Hepburn is one who maintains a high degree of name recognition today, even among people who aren’t actively interested in Hollywood history. Like John Barrymore, her name carries an aura of prestige in the acting world. Between stage, film, and television movies, her acting career spanned from 1928 to 1994. Over the course of her career, she won a record four Best Actress Academy Awards and earned eight additional nominations. Even if a person hasn’t seen any of her movies, they might know her from being played by Cate Blanchett in Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator. Plus, her reputation for being independent and challenging societal norms makes her someone many people today can admire for that reason alone. But while her legacy has certainly held up very well over time, that success didn’t come overnight.

When you look at the early years of Katharine Hepburn’s career, both in film and on stage, you’ll see that she had a pattern of having some genuinely remarkable and promising achievements followed by some setbacks. For example, just weeks after graduating from Bryn Mawr in 1928, she was promoted from understudy to star in a stage production of The Big Pond, but was fired after one performance. She made her Broadway debut later in 1928, but the show closed after eight nights. Following a few years of moving between various theater companies with varying degrees of success, she had an opportunity to appear in the stage production of The Animal Kingdom in 1931 — but was fired after both Leslie Howard and playwright Phillip Barry were dissatisfied with her performance. Her big break didn’t come until 1932 when she was appearing on Broadway in a production of The Warrior’s Wife. The play only ran for a few months, but she got good reviews from theater critics and caught the attention of agent Leland Hayward, who thought she might be right for a project RKO Studios had in the works at the time: A Bill of Divorcement.

After seeing Hepburn in action during a screen test, director George Cukor saw something special in her. He thought she was unique and unusual, but in a good way. But when she was offered the part of Sydney in A Bill of Divorcement, she requested a weekly salary of $1,500 — a rather bold move for someone who was only just getting started in the theater world and had never appeared in a film before. For context, Jackie Cooper was earning $1,500 per week around this same time, when he had just had a wave of success in hits like Skippy and The Champ and had been nominated for an Oscar. (Adjusted for inflation, that $1,500 weekly salary would be about $32,000 per week in 2022.) David O. Selznick, the head of production at RKO at the time, didn’t share George Cukor’s enthusiasm for Katharine’s screen test. He had some reservations about whether or not she’d be a hit with audiences and knew that it’d be a big risk to have her in A Bill of Divorcement, but she got the job.

In 1932’s A Bill of Divorcement, Katharine Hepburn made her film debut in a significant role alongside established stars John Barrymore and Billie Burke and it proved to be a “Star is Born” moment for Katharine. Not only was the movie a hit, she was quickly labeled an up-and-coming star to watch. Looking back at some of the original reviews for A Bill of Divorcement, it seems that it helped people see the same unique quality George Cukor saw when he first watched her screen test. In the November 1932 issue of Photoplay magazine, their (slightly backhanded) review said of her performance:

“Not since Greta Garbo first flashed before audiences in The Torrent has anything happened like this Katharine Hepburn. This girl from the New York stage is not only a fine actress — she is a great personality. Not beautiful, measured by Hollywood standards, she has something more than beauty — that thing, whatever it is, makes the great, great.”

A review of the film published in The National Board of Review in November 1932 said of her performance:

“A young and new actress, Katharine Hepburn, has the luck to have been given the part of the daughter for her first appearance in films, and the gift to make that part glow with life and beauty, a life and beauty that does not come from mere appearance but from the direct projection of an inner nature.”

The risk David O. Selznick took on Katharine Hepburn seemingly paid off and she was offered a contract with RKO. However, perhaps nobody was more surprised by the success of A Bill of Divorcement and the acclaim for her performance than Katharine Hepburn herself. She wasn’t satisfied with her performance in it and had gone off to Europe after production wrapped, convinced her career in Hollywood was over. Instead, the momentum from A Bill of Divorcement carried her into 1933, which turned out to be a banner year for her career. Over the course of 1933, she was in Morning Glory, for which she won her first Oscar, and Little Women, which was one of Katharine’s personal favorite performances of her career. She also had Christopher Strong, which wasn’t a runaway hit at the box office, but she got good notices. But as she went into 1934, that pattern of “impressive achievements followed by setbacks” started to reemerge.

In 1934, Katharine Hepburn had a hard time catching a break professionally. Film-wise, she appeared in Spitfire, which turned a profit, but is generally regarded to be one of the worst movies of her career. There was also The Little Minister, which fell into the category of being too expensive to be profitable. She also appeared in a stage production of The Lake, which turned out to be enough of a fiasco that Katharine personally paid for the show to close rather than endure the humiliation of staying on with a show that was getting panned by the critics. (The Lake was the play which famously inspired Dorothy Parker to say of Hepburn’s performance, “She runs the gamut of emotions all the way from A to B.”)

By 1935, she had another moment of success with Alice Adams, which was profitable and earned her another Best Actress Oscar nomination. However, that Academy Awards ceremony was the year after the infamous controversy around Bette Davis being snubbed for Of Human Bondage. So when Bette won for Dangerous, it was generally accepted that the Academy was making up for Of Human Bondage and even Bette Davis is quoted as saying that she thought Katharine Hepburn deserved to win that year. Alice Adams would be Katharine’s last notable career success for a while, but some of the movies she appeared in between late 1935 and 1938 would eventually go on to be seen as some of the most interesting films of her career.

On December 25, 1935, Sylvia Scarlett was released and was the first in a string of significant box office failures Katharine Hepburn starred in. Today, Sylvia Scarlett is notable for a few other reasons, though. First of all, it was the first on-screen pairing of Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant. It was also another teaming of Katharine Hepburn and director George Cukor, who had helped give her that first big break in Hollywood and was someone she would successfully work with several more times. It’s also often discussed in regards to its LGBTQ themes. However, it’s a movie that audiences of 1935 perhaps weren’t quite ready for. Reviews from its initial release were a mixed bag. Many critics described it as being confused and muddled and criticized the adaptation from its source material. There were some positive reviews for both Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant. But there were many critics who hated the movie in general. Here is a selection of reviews featured in the Motion Picture Review Digest:

“Sylvia Scarlett [is] an amateur movie as embarrassing as the ideas indulged in by Uncle Charlie when he dons Aunt Martha’s hat at Aunt Ida’s birthday party. I finally had to walk out on Sylvia Scarlett for a breath of Sixth Avenue monoxide…The whole picture is a case of bad judgment on the part of everyone concerned.” – Time

“I am forced to say that her vehicle is a sprawling and ineffective essay in dramatic chaos, with characters and situations enmeshed in vague obscurities, but for Miss Hepburn’s performance I have only admiration. The photoplay itself is a rather futile oddity, but the eerie suggestion of oddness that goes with the star’s characteristic type of impersonation fits in far more successfully with this sort of tale than it ever did when she was attempting to be a small-town wallflower in ‘Alice Adams.’ I don’t care for ‘Sylvia Scarlett’ a bit, but I do think Miss Hepburn is better in it than she was as the Booth Tarkington heroine.” – NY Herald Tribune

“Except for the excellent people in it, and especially the beautiful and talented Katharine Hepburn, who animates the title role with a vibrant and compelling performance, there is very little to recommend in the [film].” – NY World-Telegram

“As the awkward, imaginative, tremulously frustrated heroine of the tale, Miss Hepburn is on her home grounds, and she plays the part with a richness of understanding that compares favorably with her performance in ‘Alice Adams.’ Individual scenes of laughter and heartbreak come through cleanly, but the story and its people seem purposeless and possess the blurred out lines of shapes that are being projected through a veil.” – New York Times

Sylvia Scarlett lost $363,000. In 1936, Katharine Hepburn only appeared in two movies: Mary of Scotland and A Woman Rebels. Neither of them were hits at the box office. Mary of Scotland lost $165,000 and A Woman Rebels lost $222,000. 1937’s Quality Street didn’t fare much better and lost $248,000.

At this point, Katharine Hepburn was facing two major problems. First, there were the films themselves. RKO largely misjudged what types of films would work best for her sensibilities. Little Women was a hit, but more historical dramas were not necessarily what audiences wanted to see her in. Today’s movie audiences have the benefit of understanding that a large part of Katharine Hepburn’s enduring appeal comes from her distinctly modern attitudes, so movies like Mary of Scotland simply weren’t the best showcase for her talents. The second problem was her relationship with the media and her image with the general public.

When Katharine Hepburn first came to Hollywood, she wasted absolutely no time in shaping that very distinctly Katharine Hepburn image that she remains defined by. Right off the bat, she avoided doing interviews and other publicity events and it didn’t take long for reporters to start losing their patience. A Bill of Divorcement was released in November 1932 and by December 1933, Screenland magazine was already frustrated enough with her that they published an open letter from the editor berating her for not being more media friendly. In this letter, the editor of Screenland criticizes her for stealing Garbo’s anti-publicity schtick, saying it has never been modern. Other highlights of that letter include:

“So you see, you have a responsibility of a sort. And it isn’t American to put your hand in front of your face when the cameras are aiming at you. Not at all. The only Americans who do that are public enemies. Our public idols, on the other hand, including our Presidents, put up with it. Mellon and Morgan stand for it…It may be a bore, but it’s a part of their business and they know it and they do it. Suppose you see if you can grin and bear it.”

“…And now, when the camera boys surround you because you’re a big name and they have a living to make, you cover the famous features with a disdainful gloved hand and let them make the most of it.”

“Oh, now. Can’t you be human? Can’t you be real? Must the ‘regular’ Katharine Hepburn from Hartford, Connecticut become merely a bored celebrity? For one thing, it’s too early in the game to be like that. You’ve made a sensational screen success, second to Garbo’s. But you’ve also had some great breaks. RKO, with wonderful wisdom, about-faced on your films after your second, ‘Christopher Strong,’ with the splendidly appealing ‘Morning Glory’ and now the great Jo role in ‘Little Women.’ I hope RKO will always be that wise. But it’s the test of time and good pictures that makes a really great star. The Hepburn-conscious public must be won not once but over and over again. Hepburn, the actress, can do it…But it’s Hepburn the girl who must pass critical muster of the personality-mad public.”

With A Bill of Divorcement being such a success, people were eager to know more about this new star. But since she wasn’t playing into the traditional movie star media system, she was something of an enigma to the public. Some of the information journalists were getting was contradictory. Many articles about her early days in Hollywood talk about her unusual style of dressing. There were rumors she was the heiress to a $16 million fortune. She created buzz for buying a used car rather than a brand new one. (She explained to Movie Classic magazine in a May 1933 interview, “I have no false pride about driving a second-hand automobile; rather I’m proud of having struck a good bargain.”) Her marriage to Ludlow Ogden Smith, which she had been trying to keep quiet, was a curiosity unto itself. She hardly shared Joan Crawford’s enthusiasm for responding to fan mail and signing autographs.

On top of all that, there were often articles describing her as being rude, aloof, or generally difficult to work with. In September 1934, Picture Play magazine published an article titled “Hartford Resents Hepburn!” which accused her of being too aristocratic and out of touch to even win over the residents of her hometown. In January 1935, Hollywood magazine ran an article titled “Spitfire Hepburn Reforms,” describing her as having turned over a new leaf and how she had gone from being the bane of the RKO publicity department to being very cooperative for promotion of The Little Minister. By August 1937, there was enough Katharine Hepburn controversy for Picturegoer Weekly to publish a detailed timeline of her shaky relationship with the media, not unlike the articles you might see today breaking down timelines of drama around the movie Don’t Worry, Darling.

Between the bad press and the string of box office failures, it was clear in 1937 that something had to change in Katharine Hepburn’s career and Stage Door was a step in the right direction. Stage Door was only a modest success financially, but it was well received and gave Katharine a chance to get away from costume dramas and into a well-written drama with an excellent ensemble cast. (Plus the popularity of Ginger Rogers to help bolster its box office appeal.)

Looking back at Katharine’s run of Stage Door and 1938’s Bringing Up Baby, it’s easy to see this as a golden streak. But while Stage Door did respectably well, Bringing Up Baby was a different matter. Bringing Up Baby is one of the most notable examples of a classic film that wasn’t a huge hit when it was first released. Today, it’s a quintessential screwball comedy. But when it was released in February 1938, it was a movie that got some pretty respectable reviews, but didn’t perform as expected at the box office. One review published in Variety said of it:

“It completely ignores anything smacking of sophistication. It doesn’t even pretend to be witty. It just dishes out plain, boisterous comedy of a brand calculated to hit the greatest number of customers in the midriff. And it will hit them for plenty of box office. At the same time, Bringing Up Baby will be rated one of the distinctive entries of the season in this classification — the most frantic and whirligig of recent film funnies.”

Variety also said of Brining Up Baby in a separate review:

“Picture is moulded along same lines [as ‘Awful Truth’] and is definite box office. ‘Bringing Up Baby’ is constructed for maximum laughs. There is little rhyme or reason for most of the action, but it’s all highly palatable…Under Howard Hawks’ skillful pacing it is a hilarious farce.”

A critic for the New Yorker wrote:

“Little did I ever dream that in a Hepburn picture there would be such a flibbertigibbety farce as that of the lady whose skirt is ripped from her in a restaurant, but Miss Hepburn adds charm to the informal predicament and never has seemed so good natured.”

Newsweek also called it an “above average contender for crackpot-comedy sweepstakes,” praising the direction from Howard Hawks and Katharine Hepburn’s first farcical performance, while also noting the movie tries too hard for laughs at times. A selection of comments from theater owners published in the June 4, 1938 issue of Motion Picture Herald are also generally positive toward Bringing Up Baby and Hepburn’s performance in it. Even the most critical of the theater owner comments featured in that issue still called Bringing Up Baby better than most other screwball comedies coming out of Hollywood at the time, but blamed its disappointing performance on audiences losing interest in that style of comedy.

Despite the generally good reviews for the movie and for Hepburn, Bringing Up Baby didn’t become profitable until it was reissued for a second theatrical run in 1940. It was the last Katharine Hepburn movie released before the infamous Box Office Poison ad was published by the Independent Theater Owners Association. While RKO had been trying to revive interest in Katharine Hepburn, she didn’t feel confident in her future at RKO and opted to buy out the remainder of her contract. The underperformance of Bringing Up Baby also had some collateral damage for Howard Hawks, who lost out on the chance to direct 1939’s Gunga Din because of those box office returns.

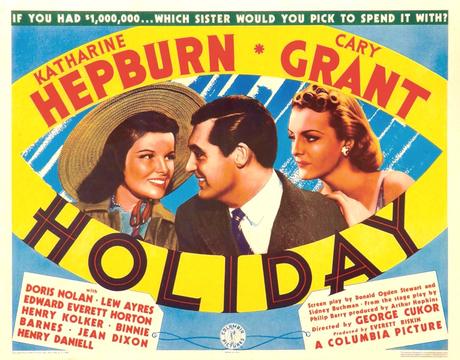

Katharine’s second movie of 1938, Holiday, was released by Columbia and was another chance for her to work with both Cary Grant and George Cukor. Today, adding Holiday to that run of Stage Door and Bringing Up Baby makes 1937-1938 look like a true high point of her career. Many actors would love to have a run of movies like that in their careers. Holiday is now frequently cited as one of Katharine Hepburn’s best movies and firmly established as a comedy classic. But, as was the case for Bringing Up Baby, Holiday was generally well reviewed by critics, but struggled to make a mark with audiences. Reviews from newspapers and trade papers featured in the June 27, 1938 issue of the Motion Picture Review Digest were more positive, overall, about Holiday than they were for Bringing Up Baby but a selection of theater owner comments from the September 17, 1938 Motion Picture Herald mostly amount to one main sentiment: audiences just weren’t into it.

With the disappointing performance of Holiday, Katharine started to take matters into her own hands. She left Hollywood and started setting the stage, quite literally, for what would go on to become one of the biggest comebacks in Hollywood history. Playwright Phillip Barry had written The Philadelphia Story specifically with Katharine Hepburn in mind and the play proved to be exactly what her career needed. The Philadelphia Story opened on Broadway on March 28, 1939 and became a major success. Naturally, it was only a matter of time before movie studios were interested in doing a film version of the stage hit. At the time, Katharine had been seeing Howard Hughes and he realized how important it would be for her to hold the film rights to the play. He purchased the rights to The Philadelphia Story and gave them to her as a gift, putting her in the position to return to Hollywood on her own terms. She ended up selling the film rights to MGM, where she was able to choose her costars, director, and screenwriter, in addition to starring in it herself.

The Philadelphia Story was a big financial and critical success for MGM, earning a profit of $1,272,000 and six Academy Award nominations. Katharine was nominated for Best Actress, but lost to her Stage Door co-star Ginger Rogers. Jimmy Stewart and Donald Ogden Stewart respectively won for Best Actor and Best Screenplay. The movie also earned a Best Picture nomination and a Best Director nomination for George Cukor. Over the years, The Philadelphia Story became an established classic of the romantic comedy genre, being added to the National Film Registry in 1995 and included on several Top 100 movie lists released by the American Film Institute. The release of The Philadelphia Story also successfully started a new chapter in Hepburn’s film career at MGM, where, most notably, she began her relationship with Spencer Tracy.