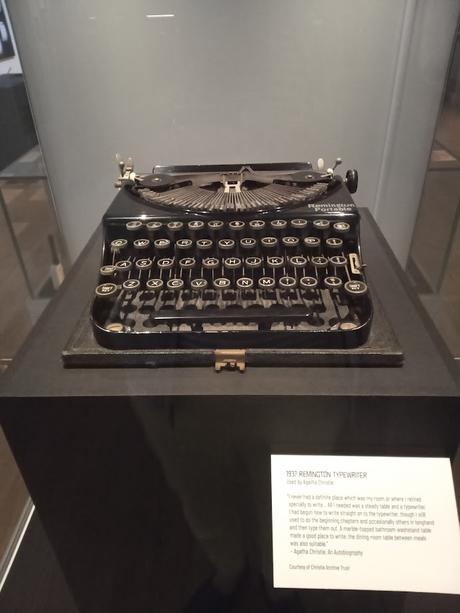

It’s been a discombobulating week, but the highlight was visiting the current Classic Crime Fiction exhibition at the University Library in Cambridge. The UL had dug into its vaults to come up with an array of first editions, which made for a lot of fun going round the display cases saying: Read that, and that, want to read that, no will never read that, etc. The real pull for me was Agatha Christie’s typewriter. I’m not really a relic person; I don’t need the bones of my saints. But I did want to see it.

The other unexpected treat was a selection of letters between P. D. James, her editor and her agent, when the agent was selling Cover Her Face. The agent’s letter was about four lines long, saying the start of this book needs a properly ruthless edit but if you can get past the awful initial slowness the characterisation is quite good. And then the editor wrote to P. D. James saying they’d be happy to publish and hoped she could forgive them for taking such an unconscionably long time to reply to her. Nothing has changed. After the exhibition I made a list of my top five classic crime novels, which are (in no particular order, it was hard enough getting down to five): 1) Josephine Tey, The Franchise Affair (just the perfect blend of cosiness and dark, dark deeds), 2) Agatha Christie, Murder on the Orient Express (it feels like a cliche after so many films, but the book is so well done it beats all the adaptations), 3) Dorothy L Sayers, Busman’s Honeymoon (could so easily have been Murder Must Advertise, only a whisker between them), 4) Agatha Christie, A Murder Is Announced (again, could so easily have been Murder at the Vicarage, which is so amusingly written) and 5) Sebastian Japrisot, Trap for Cinderella (one of the great French crime writers).

***

It was about this time last year when I received the phone call that no partner really wants to get. ‘I’m fine,’ Mr Litlove said to me. ‘No need to worry, but I’m in A & E.’ He was waiting to get stitches in a head wound.

What had he done to himself, you may ask? Well, we’d been decluttering our house for some months by this point and we had the final items to deal with – three large bin bags of teddies that for many years had been living under our son’s old bed. Mr Litlove would have taken them to the tip, but I couldn’t countenance that. I couldn’t bear the thought of all those googly eyes staring at me in sad reproach. And so Mr Litlove had gone into town to see if he could find a charity shop that would take them. He’d parked at the back of the British Heart Foundation and tried along the street and as luck would have it, one shop assistant said yes. In a hurry to be rid, Mr Litlove had jogged back to the car, and neglected to notice a metal chain slung low between two bollards. He’d broken his fall with his forehead, but been incredibly lucky not to break teeth, glasses or bones. If only he’d been carrying the bags of teddies with him – what an airbag they would have provided! But then, I began to wonder…. What if the teddies hadn’t wanted to go to the charity shop? Was it possible that unseen velour paws had pulled that unfortunate chain just tight enough?

Well, Mr Litlove was unwilling to risk a second trip, and so the teddies are still upstairs, parked there last year until we could find a solution for them. Last weekend, I thought I really should take a look. It was a nice sunny day and I thought I could put them in the garden and give them a bit of a brush up. When I told Mr Litlove, he wasn’t listening properly. ‘You’re going to have a massive teddy bear’s picnic with them?’ he asked. I sighed. ‘No, I thought I could maybe divide them into two camps, the ones that clean up okay and the others for whom all hope is lost.’ We considered the teddies. I wasn’t all that sure I wanted to be responsible for the various Sophie’s Choices that would have to be made. I said tentatively, ‘Perhaps we could give them all a small sum of money wrapped up in a spotted handkerchief and send them in groups to the bus stop to make their way in the world?’ Mr Litlove had a different idea. ‘You could sit them in a circle and get them to discuss who they’re going to vote out.’ ‘Like Big Brother,’ I said. ‘Or maybe we could do it like The Traitors. Which ones look like ringleaders to you?’ Mr Litlove held up his hands. ‘I’m having nothing more to do with them.’ I contemplated his scar, which has an uncanny resemblance to Harry Potter’s. I looked at the teddies and realised we only had two bags now rather than three, which left a whole bag unaccounted for, possibly roaming free.

The teddies remain where they are.

***

For obvious reasons I was very keen to listen to There’s Nothing Wrong With Her, Kate Weinberg’s novel of chronic post-viral illness. Vita is stuck in bed with only her goldfish, Whitney Houston, and the 16th century ghost of an Italian nobleman, Luigi del Porto, to keep her company. Luigi is the unfamous original author of Romeo & Juliet and the subject of a screenplay Vita once wrote with a former boyfriend – about whom she is having some fantasies. Her current boyfriend, Max, is a doctor and rarely home, working long hours at the hospital and even longer, Vita suspects, because he’s bored and frustrated by her condition. All she can do is suffer the tortures of what she calls ‘The Pit’, the symptomatic depths of her illness, and reflect on her complicated relationship with her younger sister, Gracie, and the traumas they endured at the hands of evil stepmother, Faye. But then, a flood in the upstairs apartment leads Vita into the company of Mrs Rothwell, an aging invalid, and her companion, American musician, Jessie, who will help her life turn in a different direction.

This is a charming, quirky, kind book about chronic illness. Weinberg copes brilliantly with the sheer plotlessness of chronic illness by having so many amusing characters circling around Vita, whether in real life or fantasy. Ironically, then, the main problem is the middle section where there’s just too much going on and it’s all a bit of a muddle. As for the depiction of illness itself – hard to do when it’s invisible for the most part – I was again impressed by the way she shows the out-of-time quality of an invalid’s life, and the immense effort it requires even to do the simplest of things. If you’ve ever experienced post-viral fatigue, I think this novel will speak to you, but I’m not so sure how clear it will be to those who’ve always led healthy lives. Weinberg wants to do something nuanced and entirely authentic by showing how previous traumas, bad life situations, grief, intense emotion and longing will all piggy-back onto poor health, magnifying it. This is true and, in its way, significant. But she runs the risk of having Vita’s condition misread as usual as psychological in origin. How you get around that, I really don’t know. But this is definitely a brave step in the right direction of making a situation that is common to thousands more people post-Covid heard and understood.