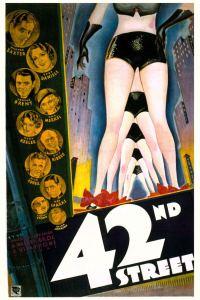

Where would the musical be without 42nd Street? When the movie was released in March of 1933, the concept of the backstage musical had already been done several times over and was quickly becoming passé. But with Busby Berkeley’s dazzling musical numbers, sharp dialogue, and catchy songs by Al Dubin and Harry Warren, 42nd Street proved to be a total game changer for the musical genre.

In the 1980s, history repeated itself on Broadway. Stage musicals based on popular films are very commonplace today, but at that time, it was viewed as a risky idea. It hadn’t been done successfully before, but 42nd Street proved that it could work. Over 40 years later, it remains one of the most popular Broadway musicals.

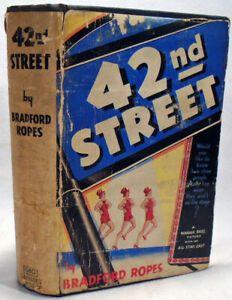

Nearly 90 years after it was first introduced to the public, 42nd Street has unquestionably earned its place in pop culture history. But what’s often forgotten is that it was originally based on a novel by Bradford Ropes. I’d long been curious to see how the book compared to the movie, but it’s been out of print for several decades which made it extremely difficult to find and extremely expensive when it could be found. So when I saw that it was just brought back into print a few months ago, I ordered a copy immediately. So, how does it compare?

Book & Movie Differences

42nd Street the movie is unquestionably a classic of the pre-Code era. It’s full of content that would have been verboten just a year and a half later when the production codes were being fully enforced. But even then, the pre-Code content that made it into the movie is just a small fraction of what was in the book.

The Julian Marsh that we see in the movie, played by Warner Baxter, is an overly-stressed Broadway director who had lost his money in the stock market crash and desperately needs this production of Pretty Lady to be a big hit so that he can afford to retire for the sake of his health. All of that was invented for the movie. What the movie leaves out is that he was originally written as a gay man whose boyfriend, Billy Lawlor, is one of the featured performers in Pretty Lady.

The character of Billy Lawlor, played by Dick Powell, is a little more prominent in the movie than in the book. In the book, Billy is a minor presence until the nearly the end when the production team is dealing with the crisis of Dorothy Brock’s injury. He’s the one who first suggests that Peggy could take Dorothy’s place in the show. The reason he suggests her over any of the other women in the chorus is because, in addition to seeing potential in her, she was the only one who was polite to him. Everyone else in the chorus snubbed him because of his status as Julian Marsh’s boyfriend. In the movie, Anne Lowell, played by Ginger Rogers, is the one who recommends Peggy.

Even though Billy Lawlor was originally written as a gay man, he actually does end up with Peggy Sawyer in both the book and the movie. Near the end of the book, he proposes a relationship of convenience to Peggy, which she agrees to. She’s well aware that this would strictly be a lavender relationship, but she appreciates how such a relationship would be beneficial for both of their careers.

Generally speaking, the book spends a lot more time covering the various affairs and platonic relationships between characters than the movie does. In the book, much attention is given to Peggy Sawyer being romantically torn between Terry, another performer in the show, and Pat Denning, the man Dorothy Brock had been cheating on her boyfriend (and financer of Pretty Lady) with. Terry is in the movie, but if you blink, you’ll miss him. And not only was Pat actively seeing both Peggy and Dorothy, he was also seeing Amy, the wife of Andy Lee, the show’s dance director. Andy and Amy have an extremely bitter marriage and she is blackmailing him over an incident in which he was caught in a compromising situation with a minor. The character of Amy and that whole storyline is completely left out of the movie.

The movie also omits the characters of a young acrobatic dancer named Polly (imagine a contemporary of June Preisser) and her pushy stage mother. The stage mother encourages her daughter to tolerate the affections of men who could help advance her career, assuring her that they won’t go too far since she is still a minor. Polly’s mother also has a vested interest in seeing Dorothy Brock get taken down a peg or two since Dorothy had one of her daughter’s numbers bumped in the show. Ultimately, she plays a role in the chain of events that leads to Dorothy’s fall.

Another very notable change between the book and the movie is the fact that Dorothy Brock actually does perform on opening night in the book. Her big accident occurs afterward. Instead, the last-minute emergency that threatens opening night is an older performer dropping dead on stage during dress rehearsal. This leads to people trying to have him declared dead in the ambulance instead of the theater to avoid an inquest that would delay the show’s opening.

Generally speaking, the movie is kinder to Dorothy Brock than the book is. Bebe Daniels was only 32 years old when 42nd Street was released and looked absolutely stunning. Hardly the aging, past-her-prime Broadway diva described in the book, who is tolerated more than she is respected. The book version of Dorothy is messier and more difficult to deal with, but the movie softens the character by giving her the scene where she visits Peggy to give her some words of encouragement. That scene does not happen in the book. However, there was a part of the book that mentioned how even performers who didn’t like each other were wishing each other luck on opening night, which could have inspired the scene in the movie.

Is the Book Worth Reading?

Considering how incredibly influential 42nd Street has been both as a movie and a Broadway show, it’s a little surprising that the book has essentially become a footnote in its own history. But now that it’s back in print, I really hope more people will discover it. Nobody’s going to put it in the same league as The Grapes of Wrath or anything like that, but it’s still a very enjoyable book; a fun summer read for fans of classic films or Broadway musicals.

If you’re a fan of 42nd Street or any of the other Busby Berkeley backstage musicals like Gold Diggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade, the book 42nd Street is well worth your time. The movie is an extremely condensed version of the book, reduced to its most essential parts. (The differences I’ve listed here are just some of the biggest differences.) Since the movie is only about 90 minutes long and the last 20 minutes are devoted to musical numbers, everything leading up to the big finale moves at a very fast pace. But with the book, you can spend more time getting to know these characters better and taking in the atmosphere of the 1930s-era theatrical world.

42nd Street is the kind of book that’s very much a product of its time. Author Bradford Ropes had worked in vaudeville and had been in the chorus of Broadway shows, so he does a great job of capturing the essence of what this scene was like. It’s clear that this was a setting he knew extremely well. He vividly describes the social hierarchies of the theatrical world and the emotions and experiences that come along with performing in a show. He also brings in details that would likely be left out if someone today tried writing a story about 1930s Broadway. For example, the book is set when vaudeville was on its way out and Broadway was forced to compete with Hollywood for big-name talent. He seemed to really understand the dynamics of that very specific moment in time.

Beyond the details about the theatrical world, I really liked his overall style of writing. There were a lot of lines in the book that I could practically hear being delivered by people like Una Merkel and Ginger Rogers. If you enjoy the very snappy style of writing you find in a lot of 1930s-era Warner Brothers movies, you’ll probably like the book version of 42nd Street. I wasn’t surprised to learn that Warner Brothers had bought the rights to the book before it was even published; it’s very much their style.

I know people are pretty exhausted with the idea of reboots and adaptations right now, but I actually wouldn’t mind seeing a new adaptation of 42nd Street that follows the book more closely than the movie or the stage version. Similar how HBO’s 2011 version of Mildred Pierce works as its own adaptation of the book rather than a straight remake of the Joan Crawford movie.

This review is part of the 2021 Classic Film Summer Reading Challenge hosted by Out of the Past. For more reviews on books related to classic film, be sure to follow the #ClassicFilmReading hashtag on social media.