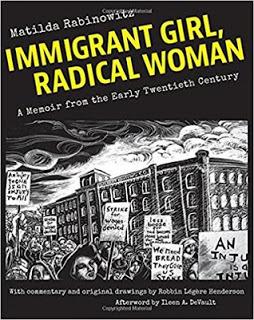

IMMIGRANT GIRL, RADICAL WOMAN: A Memoir from the Early Twentieth Century

(ILR PRESS an imprint of Cornell University Press, 2017) by Matilda Rabinowitz

(née Taube Gitel Rabinowitz) with commentary and hand drawings by Robbin

Légère Henderson

This is a fascinating, educational and engaging personal story written like a great novel rather than a typical memoir. The book is based on the diary of the main character, Matilda Rabinowitz. I highly recommend it.

The focus is on an immigrant Jewish girl arriving in America in the thick of the turbulent times ushering in the 20th-century. Anarchists, communists, and socialists are battling capitalists. The working class battles robber barons. A young woman, Matilda, begins as a foot soldier in a passel of Jews grasping “the nuances of Socialist theory, aligning themselves with the younger, radical members.”

Jews are unshackling themselves in “the Golden Medina” from Old World beliefs and

practices, immiseration, illiteracy, and pogroms. Matilda Rabinowitz is enthralled. Her ambition now is dedicated to fighting for the soul of America.

Granddaughter, Robbin L. Henderson, deftly weaves the stories about Matilda’s

childhood, treacherous trek to America, and her coming of age. She is disappointed

with the working and living conditions she finds in a land with so much more

potential. Matilda dedicates herself to social progress. Henderson shares Matilda’s

not so private and never traditional life to round out the picture. Regardless of one’s

politics, the reader sympathizes and admires Matilda Rabinowitz.

Henderson undertakes years of research to fill in historical gaps. Henderson

scrounges through archives of organizations many long out-of-business. She travels

to undertake personal interviews with survivors from the time. She includes

newspaper articles. Henderson adds original drawings appearing throughout the

book that enhance the stories, and stimulate the visual sense. It is an indelible

touch.

Matilda was no shrinking violet. She held little regard for many of her

contemporaries in the Movement. Radicals referred to Socialists in politics and soft

union leaders with the derisive terms, “municipal sewage plant” or “post-office”

Socialists. Matilda believed union leaders “assumed the privileges of the ruling

class.” It was wrong to collaborate with employers, while they saw their cooperation

as the means to higher wages, shorter hours and greater benefits. Matilda believed

they were undermining working-class solidarity.

Comfortable Jews believing nostalgic tales of a Xanadu-like religious life “in the old

country” learn the rest of the story from Matilda’s diary; why Jews ran fast by the

millions before the Nazis. “Many were the lean years. Great had often been her

terror of persecution and pogrom...My uncles were fairly well educated, but trained for nothing useful,” so earning a living was beyond reach. “The girls just waited to

get married,” and they were uneducated, because “the duties of a wife did not

include any necessity for education.” Intellectual pursuits were out of the question

because of religious discrimination and family pressures.

Matilda tells us of her harrowing tale how “mules” directed Matilda’s family across

Europe to unfamiliar ports for transport, sneaking and bribing their way across

borders, scrounging for food and warm places to sleep. Sound familiar? Matilda is

not reported to ever practice Judaism again. She believes in America’s promise and her opportunity to repair the world through radical Socialism, labor organizing, and avant-garde feminism. Matilda fights for better working conditions and pay, eliminating child labor, improving public health and living conditions, and reordering of the government’s responsibility to its people. These were heady times and Matilda’s work helped build a middle class where none existed before.

Her turn politically left might be traced to, “The shock and disappointment with

(New York) city that I had pictured in my childish imagination” creating a sense of

alienation and a feeling of not belonging, the ”deadening factory work and

exploitation they experienced from the time of their arrival in the United States.”

Matilda wrote articles for The International Socialist Review. Her claque in the IWW

(International Workers of the World—Wobblies) was dedicated to “agitating and

organizing, organizing and agitating.” She believed “in the precept of the IWW

preamble: It is the historic mission of the working class to abolish capitalism.”

She held quarter for the nascent Zionist Movement. Henderson tells the reader,

“Matilda was an internationalist and an anti-Zionist.” She rejected the term “cultural

pluralism” coined by the ardent Zionist and prominent intellectual liberal of the

time, Horace Kallen. She was more concerned for the Japanese Americans interned

during the war under Executive Order 9066 than for the remnants of the Holocaust.

Matilda bristled at “Jewish exceptionalism.” That “offended her democratic

sensibilities and her international beliefs.” For Matilda, the Zionist project was a

theocracy and she long before abandoned Judaism and her Jewishness. Henderson

explains in simple straightforward terms the Left’s rejection of Israel till today.

There are many first-hand stories about Matilda’s agitating and organizing, but one

of the best is how Matilda enthralls workers at Studebaker auto plant to stage the

nation’s first auto factory strike. “Some historians credit Matilda at Studebaker with

forcing (Henry) Ford fearing unionization, to increase his workers’ salaries to five

dollars a day.” The notorious anti-Semite who detested unions a little more than

Jews found in Matilda the inescapable nemesis.

Between 1900 and mid-century, Matilda and other activists designed a web of new

social policies: equal pay for equal work, no to child labor, women’s rights, decent

wages and working conditions, improving public health, birth control, AFDC and

Maternal and Child Health Care, free public education and public housing. Matilda

was in the thick of the perfect storm rampaging for a century. She and the activists

named in the book had what it takes to change a nation; she was stentorian,

sagacious, and full of brio.

The book is replete with names of activists and union leaders. Matilda knew and

worked with many of them. Matilda writes about the Federal Children’s Bureau

(1912). Midway in my career, I was interviewed and hired by Dr. Martha May Eliot

(born 1891) to head a Massachusetts children’s advocacy center. Dr. Eliot and

Matilda must have crossed paths. Dr. Eliot was a feminist and health activist. AFDC,

child health programs, and child labor laws were her main focus. Matilda worked on

a study of infant mortality for the Federal Children’s Bureau working as a statistical

assistant and interpreter where Dr. Eliot spent much time.

Matilda thinks about the impact of industrialization taking hold. How it brings about

job cuts and changes the nature of work. She senses the changing attitudes to unions

and organizing workers with the burgeoning white-collar office workers. They

quickly outnumber factory floor workers. The same conversation prevails in 2018

using the sobriquets of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning.

Her personal life is nettled by poverty and love affairs with characters. Matilda

suffers repeated bouts of poverty. She and her baby depend on the good acts of

friends and family. She was underemployed or unemployed for long periods. The

book never quite satisfies the reader why she does not retain the good paying jobs

over the long-term despite Matilda’s talents for language, diligence, and innate

smarts.

Henderson admires her grandmother but there is no pretense. Henderson writes

truthfully with affection and admiration. Matilda’s diary has not vaunted or given to

self-aggrandizement like in so many memoirs. For instance in an effort to embarrass

Matilda the organizer, local papers published love letters exchanged between

Matilda and her married paramour, father of her child but not her husband. These

are included in the book.

Matilda’s story strengthens the resolve of women to find their own place in society

in their own time and be inspired. I will recommend Immigrant Girl, Radical Woman

to my college students as a must read.

Harold Goldmeier is a writer and college teacher in Tel Aviv with a degree from

Harvard. He is an award-winning businessman and public speaker @

[email protected]

------------------------------------------------------

Reach thousands of readers with your ad by advertising on Life in Israel ------------------------------------------------------