This review and the novel contain strong language.

This review and the novel contain strong language.

It’s an occupational hazard of literary blogging that people are always asking if you’ve read a particular book, and if it’s one that everybody’s talking about I usually do cave in even it doesn’t particularly appeal to me, just to stay in the loop.

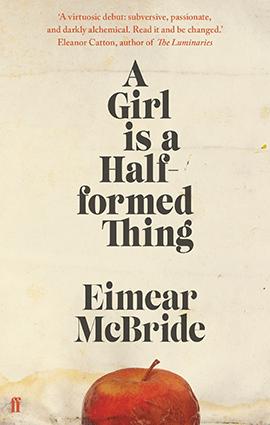

There were some strange reasons I did and didn’t want to read Irish author Eimear McBride’s debut novel A Girl is a Half-formed Thing, which won the Bailey’s Women’s Prize for Fiction and the Desmond Elliot Prize for New Fiction. I’d seen the ubiquitous quote of the opening lines demonstrating (although not entirely representative of) the experimental style and knew the subject matter was very dark, tantamount to a ‘misery memoir,’ albeit fiction. I’m not sure I’ve ever been scared to read a book before.

And yet. This is, famously, a book which took only six months to write and then failed to find a publisher for nine years until the tiny Norwich-based independent Galley Beggar Press had the courage to take a punt on it (it’s now published in paperback by Faber). Eimear McBride took the opportunity in her speech accepting the Bailey’s Prize to make some points that are very important to both readers and writers, urging publishers to be bolder in their choices and to give the reader more credit. “There are serious readers who want to be challenged, who want to be offered something else, who don’t mind being asked to work a little bit to get there.” And that did speak to me.

Just as this isn’t a book that can be read in the usual way, it’s also difficult to evaluate against standard critical benchmarks, many of which have no relevance. So this is more of a personal response on my part.

A Girl is a Half-formed Thing is the unnamed girl’s first person, stream of consciousness account of her relationship with her older brother who is permanently affected by a brain tumour in early childhood. It opens with Girl still in the womb and the early chapters are extremely challenging.

You bent over. Don’t cry don’t cry. Trot it out. I think I might. Don’t. Whinge gets beats for you or me. Wooden spoon worse than hands or clip on the ear. I’ll give you something to cry about.

I hung in there – and this surprised me – because the Catholicism was a cultural framework I recognize and it allowed me to get my bearings in a story where that is hard to do. This prose does not conform to any conventions of grammar, syntax or coherence. It spurts, drips and splatters but rarely flows. That is both a huge barrier and the work’s defining strength, for there is nothing new about an Irish novel dealing with misery, sin and abuse.

It takes a while to acclimatise to the choppy rhythm but by the second part where Girl and Brother reach adolescence I was pulled under and committed to staying the course (and I’ve abandoned at least eight mainstream novels which failed to engage me this year). It was like a game trying to decode what was on the page and tease out the story from the abstractions.

There is nothing about this book that could be described as fun (although there are some funny moments) but this was a satisfying exercise which calls into question the way we generally use language and all the unexploited possibilities it holds. In a literary landscape where too much is spoon-fed and spelled out, this is a masterclass in the opposite approach. It must have been incredibly liberating to write.

The highly fragmented voice of Girl’s consciousness was initially something of a mystery as it seemed at odds with someone of at least normal IQ, who gets good grades at school and goes off to study at college. But as the story progresses it starts to makes sense as the expression of everything she experiences, is subjected to and becomes. No wonder she’s so fucked-up. It’s so visceral it feels like it might be catching.

The stylistic challenges of this narrative were easier for me to deal with than the emotional toll it takes. At its most fundamental level this is a heartwrenching story of love, loss and an exceptionally strong sibling bond. The sadness of it was almost unbearable; it didn’t remind me of grief, it felt like it. But in as far as grief can only spring from love, there is something beautiful about that, and about much of the writing.

At the end of the day you shuffle with us as we leave. Down the corridors slowly and into the lift. Say goodbye. I see you dither and could never help being so cruel so Do you know your way back? I say. I know where I’m going you said to me. Soft and forgetful is what I see. Red in pajamas. That white as walls. Face. Neat bites of stitches.

No such compensation exists when it comes to the unremitting sexual degradation, masochism and violence – truly, the cruelty of fate pales next to the human kind. I had overheard conversations about the ending of this book on Twitter and all the way through was trying to guess just how awful it might get. Two of the horrible possibilities my imagination threw up didn’t come to pass (or at least I don’t think they did) but I was not misled by others’ opinions (nor by my original instincts) and found the denouement sickening, violating and profoundly disturbing.

Eimear McBride has achieved her aim of pushing the novel form towards its limits. I wouldn’t relish a trend for novels written like this and I very much doubt that’s on the cards. But this one in all its terrible brilliance is really something to have survived.

Maybe I should try Ulysses after all.

*POSTSCRIPT*

My current personal challenge (always got to have one!) is to write the first draft of a second novel in six months. As my sons are away next week I will disappear from your screens and hopefully make a big dent in it. If I’m on course to meet my target of 40,000 words by mid-August I’ll write a blogpost when I resurface.