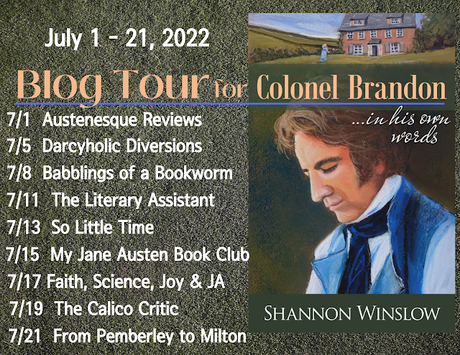

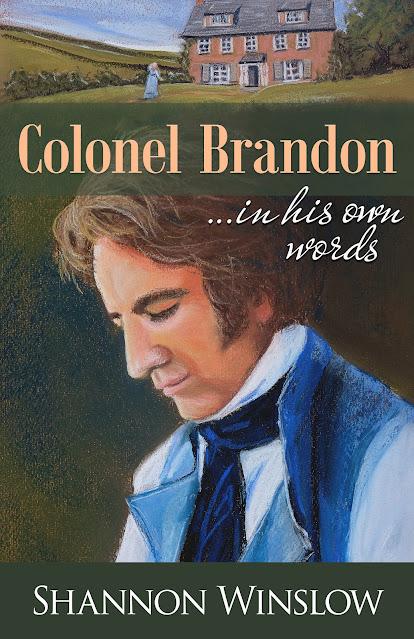

ABOUT THE BOOK

Colonel Brandon is the consummate gentleman: honorable, kind almost to a fault, ever loyal and chivalrous. He’s also silent and grave, though. So, what events in his troubled past left him downcast, and how does he finally find the path to a brighter future? In Sense and Sensibility, Jane Austen gives us glimpses, but not the complete picture.

Now Colonel Brandon tells us his full story in His Own Words. He relates the truth about his early family life and his dear Eliza – his devotion to her and the devastating way she was lost to him forever. He shares with us a poignant tale from his military days in India – about a woman named Rashmi and how she likewise left a permanent mark on his soul. And of course Marianne. What did Brandon think and feel when he first saw her? How did his hopes for her subsequently rise, plummet, and then eventually climb upwards again? After Willoughby’s desertion, what finally caused Marianne to see Colonel Brandon in a different light?

This is not a variation but a supplement to the original story, chronicled in Brandon’s point of view. It’s a behind-the-scenes look at the things Jane Austen didn’t tell us about a true hero – the very best of men

COLONEL BRANDON, WHAT KIND OF HERO IS HE?

(guest post by Shannon Winslow)

As for Colonel Brandon in particular, he is described in Sense and Sensibilityas: …silent and grave. His appearance however was not unpleasing, in spite of his being in the opinion of Marianne and Margaret an absolute old bachelor… but though his face was not handsome, his countenance was sensible, and his address was particularly gentlemanlike. By all he says and does, we know he’s a really good guy.

One reader commented to me that Colonel Brandon “was always a favorite hero of mine because he is quiet and has that tender need to save and protect.”

Yes, he’s always trying to protect and serve, isn’t he? - especially women, which is a very noble trait. And, just as importantly, imo, he is quietabout it. Personally, I can’t stand a show-off – a man who is loud and always demanding, “Look at me! Look at me!” That’s the last thing modest Colonel Brandon would do. Indeed, he’d be quite uncomfortable to know that I, for one, consider him a hero!

I didn’t set out to make heroes and heroism a central theme of this book, but it kept coming up, I noticed. In fact, it’s mentioned around 30 times! And towards the end, the colonel and Marianne have an interesting debate about what the definition of heroism ought to be. Here’s a slightly edited snippet, as narrated by Colonel Brandon:

“…Someday I should like to listen to somewhat of your own experiences, Colonel, but I must say that I have not yet stopped thinking about Major Dunston’s.”

“I am surprised to hear it. As you now know, he was a very ordinary man – more of a failure than a hero.”

“So you have said more than once, and I know that must be what you believe. But I disagree,” she announced resolutely. “In fact, that is the part I cannot stop thinking about: your poor opinion of him. If you will not stand up and call your friend a hero, I must!”

I was quite stunned by this outburst. It took me a moment to respond. “I should never wish to contradict you, Miss Marianne, but I must indeed ask for clarification. On what grounds can you possibly call Major Dunston a hero?”

“Ah, so you are prepared to listen?”

“Of course.” She had my full attention.

“I have my case well prepared. You shall hear my evidence and then we shall see if I have not convinced you.”

“Agreed.”

She leant forward and held up one finger to start, adding to it as she went along. “First, Major Dunston proved self-sacrificing by giving all his money for a cause that could not benefit himself. Second, you must admit he was brave in being willing to risk his future and possibly his life, all to help a person he barely knew.He saw a woman in danger, and he acted without hesitation to protect her, ready to go to great lengths to do so. Not one in a dozen men would have done as much. No! Not one in a hundred! Furthermore – and here is my third and most important point, Colonel – I must dispute one of your assumptions, which I consider faulty. Contrary to what you apparently believe, one does not need to be successful to be considered heroic, otherwise valiant soldiers who die in battle for a great but losing cause would be known as failures. And they are not.” With this, she sat back and folded her hands, looking confident of her victory.

I quickly came up with an objection. “That is hardly the same thing, Miss Marianne. Fallen soldiers may be called heroes, but… as I told you, Major Dunston did not die. In fact, he suffered no harm at all.”

“Come now, Colonel, do you mean to tell me that you think it is by their deaths these fighting men I spoke of were made heroes? That sounds more like something I once might have said. No, dying does not make a man heroic; it is how he lives. It was while the soldier lived that he chose to serve his country and brave the perils of battle. While he lived, he declared himself willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for the noble cause. By my definition at least, he would be a hero whether he returned home safely or died on the field of honor.”

I looked at her, somewhat awed by this line of reasoning, which was new to me.

“Well, Colonel, what do you say? Are you persuaded? …Have I convinced you that your friend Major Dunston is a hero after all?”

“You have certainly made him an excellent defense, Miss Marianne. I am quite impressed. I suppose if you wish to think him a hero, I shall raise no further objection. As for me, you must grant me some little time to consider your arguments and adjust my thinking.”

It was true. Her impassioned defense of Major Dunston, her innovative interpretation of his actions, had astounded me. That, in spite of everything, she should consider him a hero, not a pitiful failure… It was a revolutionary perspective deserving study, but it would not easily supplant all I had been used to believing for so long.

As for the missing bits of this debate about Major Dunston (and why it’s so significant to the plot and to CB!), I must refer you to the book itself. To tell any more here would be a definite spoiler.

Let us just agree that Colonel Brandon is a worthy hero, whether he admits to it or not. He’s one of Austen’s more activeheroes, actually. He doesn’t just talk a good game; he does something about it. As a teenager, he attempts an elopement to save Eliza from his father’s machinations. Then he leaves home to go to India shortly thereafter, displaying initiative and valor during his military years. He searches diligently for Eliza when he gets home, rescuing both her and another from the misery of a debtor’s prison. He fights Willoughby in a duel in defense of a lady’s honor. He takes it upon himself to fetch Mrs. Dashwood when Marianne is ill. And so much more.

I hope you will read his FULL story: Colonel Brandon in His Own Words. It’s about a true hero and the very best of men.

Shannon Winslow