Spike Lee's BlacKkKlansman (2018) puts its director back into the cultural spotlight, winning him box office and acclaim (including a Best Picture nod) unseen since his heyday in the '90s. In a year of racially charged films, from blockbusters (Black Panther) to indie films (Blindspotting) and feel-good Oscar bait (Green Book), Lee's tale of historical bigotry stands out. Klansman's mix of dark comedy and white-hot anger makes for compelling viewing, even if it's often undercut by Lee's heavyhandedness.

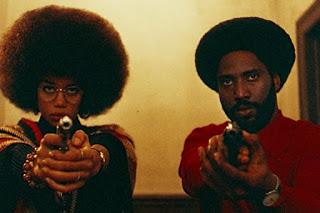

Spike Lee's BlacKkKlansman (2018) puts its director back into the cultural spotlight, winning him box office and acclaim (including a Best Picture nod) unseen since his heyday in the '90s. In a year of racially charged films, from blockbusters (Black Panther) to indie films (Blindspotting) and feel-good Oscar bait (Green Book), Lee's tale of historical bigotry stands out. Klansman's mix of dark comedy and white-hot anger makes for compelling viewing, even if it's often undercut by Lee's heavyhandedness. In 1972, Ron Stallworth (John David Washington) joins the Colorado Springs Police Department. Ridiculed and relegated to clerical work, he finds his calling as an undercover detective. His bosses want him to investigate Black Power groups, but Stallworth alights on a local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. He answers a newspaper advertisement posing as a white man, sending colleague Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) to impersonate him. Ron and Flip discover that the local Klan's not only spreading hate but plotting terrorism, with the evident sanction of Grand Wizard David Duke (Topher Grace).

Loosely based on Stallworth's memoirs, BlacKkKlansman changes the timeline (Stallworth's real assignment began in 1979) and focus (rather than foiling terrorist plots, he uncovered Klansmen serving at a local military base) of his investigations. No matter: Hollywood's rarely put me stock in historical accuracy. Rather, it's an obvious but effective attempt to extrapolate historical racism on our current, explosive moment, when white supremacists control the government and march openly in the streets. The issues Ron Stallworth battles in the era of Richard Nixon and Stokely Carmichael resonate, now more than ever.

Lee and his team of screenwriters frame Stallworth's actions through the prism of his personal dilemma. He's suspect both to the Establishment through his haughtiness and unapologetic Afro and fellow blacks like activist Patrice (Laura Harrier), who look askance at his polished language and deference to authority. Stallworth impresses colleagues through the boldness of his undercover mission and his determination to do good, leaving only bigots like Patrolman Landers (Fred Weller) unimpressed. Like its protagonist, Klansman walks a tightrope between wholesale condemnation of law enforcement and recognizing those, like Ron and Flip, who use police power for good.

Lee and his team of screenwriters frame Stallworth's actions through the prism of his personal dilemma. He's suspect both to the Establishment through his haughtiness and unapologetic Afro and fellow blacks like activist Patrice (Laura Harrier), who look askance at his polished language and deference to authority. Stallworth impresses colleagues through the boldness of his undercover mission and his determination to do good, leaving only bigots like Patrolman Landers (Fred Weller) unimpressed. Like its protagonist, Klansman walks a tightrope between wholesale condemnation of law enforcement and recognizing those, like Ron and Flip, who use police power for good. Indeed, Klansman's strength is its attempt to frame characters and their conflicts, however exaggerated, in nuanced terms. Lee harbors an instinctive sympathy for the Black Power activists Ron associates with, giving Corey Hawkins a cameo as a charismatic Stokely Carmichael. Lee views Ron's working through the system as complementary to more radical action, rather than opposed. Similarly, he has more time of day for white liberals like Flip willing fight for the same cause than he showed in, say, Malcolm X. On the other hand, Flip's character arc suggests both frustration with his assignment and possibly even temptation, with one ambiguous scene suggesting he might even be imbibing Klan ideology despite his Jewish background.

The film's Klansmen represent an intriguing cross-section, from scurvy redneck Felix (Jasper Pääkkönen) to friendly middle class Walter (Ryan Eggold) to the genteel David Duke. This gives the movie a texture lacking in more conventional Civil Rights dramas like Mississippi Burning, which present their bigots as such snarling cartoons that the audience's biggest rednecks will come out hating them. Some of the movie's most unsettling moments come from the banality of character's racism, from Felix's wife (Ashlie Atkinson) chirping about the impending slaughter of blacks to Duke's country club chumminess. If all racism came as obvious as Felix's frothery, it would be much easier to defeat.

Despite all this, BlacKkKlansman's speechmaking seems extreme even by Lee's standards. It opens with a faux-educational film, featuring Alec Baldwin as a Southern professor lecturing about white supremacy. If Baldwin's casting isn't enough of a shot at Trump, his rhetoric quotes modern Republicans, adding jabs at Hillary Clinton for good measure. Echoing Bamboozled (whose exploration of blackface sadly seems more prescient now than twenty years ago), Lee intersperses footage of Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind to demonstrate how deeply racism's seeped into our culture.

Despite all this, BlacKkKlansman's speechmaking seems extreme even by Lee's standards. It opens with a faux-educational film, featuring Alec Baldwin as a Southern professor lecturing about white supremacy. If Baldwin's casting isn't enough of a shot at Trump, his rhetoric quotes modern Republicans, adding jabs at Hillary Clinton for good measure. Echoing Bamboozled (whose exploration of blackface sadly seems more prescient now than twenty years ago), Lee intersperses footage of Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind to demonstrate how deeply racism's seeped into our culture. The opening's clunky, but later scenes are even more on-the-nose. A scene where singer and Civil Rights icon Harry Belafonte narrates an historical lynching is unsubtle, yet fits the material. Less successful is Lee's shameless audience tweaking, as when Ron assures Flip that a man like David Duke could never be president (cue musical sting!). Or a meeting where Klansmen chant "America First!" which at least appropriates a phrase long in vogue before 2016. In the finale, Lee skirts the boundaries of taste by incorporating footage of the Charlottesville hate rally, including Heather Heyer's murder and speeches by Trump and the real David Duke.

What to make of this? Lee certainly doesn't need to sell his point so hard; being uncharitable, it smacks less of calculation than condescension, not trusting viewers to draw connections with reality themselves. But even Lee's best works, from Do the Right Thing to Clockers, brim with excess and sledgehammer messaging. And however unsubtle, the ending emphasizes Klansman's thesis that racism can't be defeated with the removal of obvious villains. Part of me wishes Lee would have toned things down, but part of me thinks he's the only filmmaker who'd even dare to make a movie this pointed in the first place.

John David Washington, son of Denzel, has the easy charisma and focused delivery of a natural movie star. He makes Ron compelling with a blend of stoic humor and quiet, focused intensity. Adam Driver scored an Oscar nod playing Flip as a well-meaning ally wrestling with insecurity. Laura Harrier is charmingly charismatic but her character feels one-note, more an ideological, sometimes romantic foil than a compelling figure. Topher Grace is a scene-stealer, granting Duke an anodyne Rotarian charm that makes his evil more effective.

John David Washington, son of Denzel, has the easy charisma and focused delivery of a natural movie star. He makes Ron compelling with a blend of stoic humor and quiet, focused intensity. Adam Driver scored an Oscar nod playing Flip as a well-meaning ally wrestling with insecurity. Laura Harrier is charmingly charismatic but her character feels one-note, more an ideological, sometimes romantic foil than a compelling figure. Topher Grace is a scene-stealer, granting Duke an anodyne Rotarian charm that makes his evil more effective. Whatever might be said of BlacKkKlansman, it's undeniably a Spike Lee joint. The splashy direction, from the action scenes and explosive dialog to retro split screens and Lee's trademark dolly shots, the mix of nuanced characters and neon-sign messaging, the electric rage coursing through the film all hearken back to Lee's days as cinema's enfant terrible. And for all Klansman's flaws and didactic messaging, I'm very glad it exists.