Martin Kippenberger. 1985. Foto: Alejandra de Argos

The relationship between the artist’s biography and his work has been a constant in art history. It is considered that art history itself, in literary form, was born in the Renaissance period when Giorgio Vasari wrote Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects from notes, anecdotes and other material collected on his travels, a series of artist biographies ranging from Cimabue to Michelangelo. Vasari’s methodology is not put into question until the second half of the 20th century, when structuralism and Derrida’s deconstructivism offer new theoretical tools with which to understand the analysis and linguistics of art.

I went into the exhibition expecting to see the major works of the most important artists from the 18th century to the present day - the exhibition, however, is less interested in the works themselves and instead focuses on taking visitors on a journey through life, identity, drama, memory and obscurity. Key moments in the artists’ lives are recreated for us through their artwork.

The common thread running through the works on display is that the artists themselves, not biographers, are responsible for the personal stories they create for themselves with their art. Literary examples of this process can be found in Franz Kafka and Gérard de Nerval: Kafka’s childhood was strongly shaped by his authoritative father, and in Nerval’s case by the death of his mother.

As I continued through the exhibition, it became clear that all the artists had suffered a tragic or difficult childhood which led them to lead a continuous search for meaning in adult life. For these artists, art is a channel for their anxieties, a source of self-knowledge. The process of creation serves as a means to reach our innermost being, our desires and impulses, or to exorcize our personal demons.

Childhood spaces are a common motif in the works on display: the artists’ first bedrooms, the houses they lived in, even their own bodies. Spaces that are both intimately tied to one’s early years, and that help form the identities we will later inhabit as adults.

The first item we see as we enter is Michelangelo Pistoletto’s highly-polished stainless-steel plate with standing figures painted on it, the steel plate acting as a mirror announcing our arrival and making it come to life. The ideas of reflection, identity and identification are present from the very start of the exhibition with this piece, and its mirror effect, and have long been present in all of Pistoletto’s work. The artist does not personally interpret reality - he reflects it back at us. Even Freud reminds us of the importance of one’s body image in creating our self identity.

"The artist is not separate from his work. I am the artist and the artwork at the same time, the creator and the Universe. The subject and its reflection. The artist and society". Pistoletto.

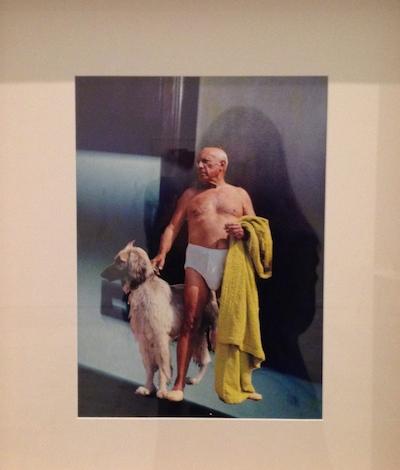

In this painting by Martin Kippenberger, an artist profoundly inspired by Picasso, he depicts himself floating in thin air dressed like the Picasso in the photo, thereby reproducing the great Andalusian painter’s identity. Kippenberger believed that self-portraits are a tragic representation of one’s own existence.

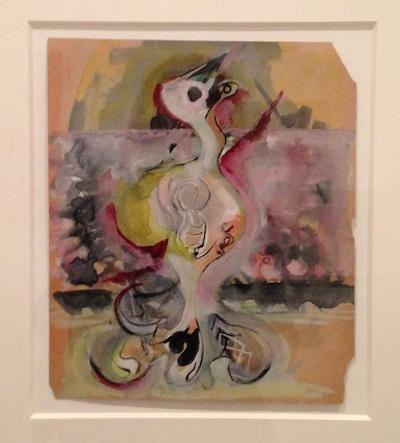

I must say this Rothko, above, took me by surprise, being as it is very different from his more typical large-scale mystical paintings. His peculiar depiction of a bird, reminds us of surrealist imagery. Rothko experimented with many painting techniques throughout his career, always looking for answers to his own doubts and uncertainties that would eventually lead him to suicide.

Philip Guston, a painter and printmaker whose work resembles cartoon strips, was interested in identifiable elements or signs of a bodily nature: toes, fingerprints and eyes.

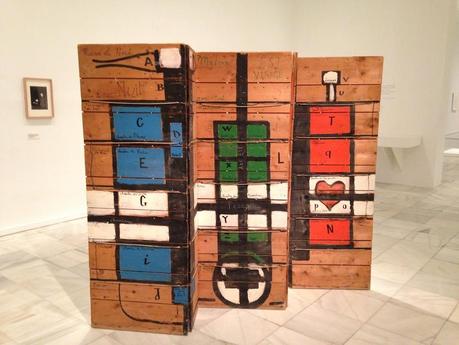

Philip Guston. Midnight Pass Road.1975. Foto:Alejandra de Argos

Edvard Munch is also present in this exhibition, a fascinating painter whose life and work were clearly and deeply affected by a tragic childhood which saw the death of his mother and the influence of an obsessively religious father. Drama and anxiety, ever-present in Munch’s life, are staples of his artwork, as we can see in this painting, The Dead Mother and Child.

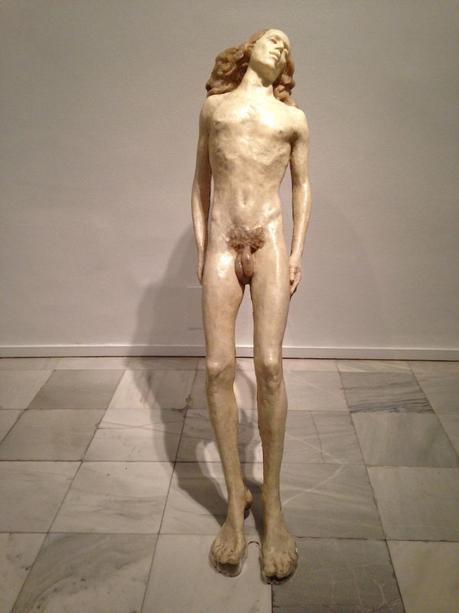

This work by Alina Szapocznikow, made out of polyester resin, looks like it’s been taken from a Pietà sculpture. The hollow figure, almost suspended in thin air, with the resin giving it an organic feel, clearly symbolizes the instability of the artist’s own life, whose mother died in a concentration camp.

"Through the traces of the body trying to fix the transparent polyester in the fleeting moments of life, its paradoxes and its absurdity. My work is difficult because the sensation experienced immediately and diffused is often rebellious to its identification. Often everything is muddled, the situation is ambiguous, sensory limits are erased "

The exhibition ends with this enigmatic sculpture by Charles Ray of a child playing with a toy car. The car, far more detailed than the child, becomes the focus of our attention, inviting us to fill in the missing information from our own memories of childhood.

Ray Charles. The new beetle. 2006 Foto: Alejandra de Argos.

The exhibition itself is strongly recommended, not least because of its invitation to reflect on our own past and present, a necessary if uncomfortable process.I’d like to end with a quote...

"He who has a why to live for, can bear almost any how."

Friedrich Nietzsche.

Dorothea Tanning. Chambre 202, Hôtel du Pavot. 1970. Foto: Alejandra de Argos

Biographical forms. Construction and individual mythology. Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid. From November 27, 2013 to March 31, 2014.