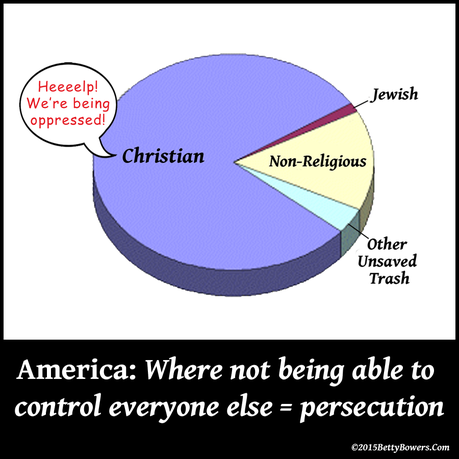

(From the Facebook page of America's Best Christian, Mrs. Betty Bowers.)

(From the Facebook page of America's Best Christian, Mrs. Betty Bowers.)The Republican officials in Indiana have decided that their fundamentalist base was being oppressed because they could not legally discriminate against those they didn't like -- so they passed a law to allow that discrimination. Now any nut-job in that state can freely discriminate against anyone he/she wants. All they have to say is that not discriminating against that person (or group) would violate their "sincerely held" religious views.

This is a shameful law in a country like our -- a country that claims to believe in freedom, equal opportunity, and equal rights under the law. And there has been a huge backlash from decent citizens in this country against this reprehensible law.

Governor Pence and other GOP officials are now trying to play down the terrible thing they did in passing that law. They are now trying to claim that their law is no different from a federal law and laws passed in several other states. The problem with that is it's just not true. Their law goes further than the federal law or the law in most other states. Garrett Epps points out the differences in an excellent article for The Atlantic. Here is part of that article:

I don’t question the religious sincerity of anyone involved in drafting and passing this law. But sincere and faithful people, when they feel the imprimatur of both the law and the Lord, can do very ugly things. There’s a factual dispute about the new Indiana law. It is called a “Religious Freedom Restoration Act,” like the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, passed in 1993.* Thus a number of its defenders have claimed it is really the same law. Here, for example, is the Weekly Standard’s John McCormack: “Is there any difference between Indiana's law and the federal law? Nothing significant.” I am not sure what McCormack was thinking; but even my old employer, The Washington Post, seems to believe that if a law has a similar title as another law, they must be identical. “Indiana is actually soon to be just one of 20 states with a version of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, or RFRA,” the Post’s Hunter Schwarz wrote, linking to this mapcreated by the National Conference of State Legislatures. The problem with this statement is that, well, it’s false. That becomes clear when you read and compare those tedious state statutes. If you do that, you will find that the Indiana statute has two features the federal RFRA—and most state RFRAs—do not. First, the Indiana law explicitly allows any for-profit business to assert a right to “the free exercise of religion.” The federal RFRA doesn’t contain such language, and neither does any of the state RFRAs except South Carolina’s; in fact, Louisiana and Pennsylvania, explicitly exclude for-profit businesses from the protection of their RFRAs. The new Indiana statute also contains this odd language: “A person whose exercise of religion has been substantially burdened, or is likely to be substantially burdened, by a violation of this chapter may assert the violation or impending violation as a claim or defense in a judicial or administrative proceeding, regardless of whether the state or any other governmental entity is a party to the proceeding.” (My italics.) Neither the federal RFRA, nor 18 of the 19 state statutes cited by the Post, says anything like this; only the Texas RFRA, passed in 1999, contains similar language. What these words mean is, first, that the Indiana statute explicitly recognizes that a for-profit corporation has “free exercise” rights matching those of individuals or churches. A lot of legal thinkers thought that idea was outlandish until last year’s decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, in which the Court’s five conservatives interpreted the federal RFRA to give some corporate employers a religious veto over their employees’ statutory right to contraceptive coverage. Second, the Indiana statute explicitly makes a business’s “free exercise” right a defense against a private lawsuit by another person, rather than simply against actions brought by government. Why does this matter? Well, there’s a lot of evidence that the new wave of “religious freedom” legislation was impelled, at least in part, by a panic over a New Mexico state-court decision, Elane Photography v. Willock. In that case, a same-sex couple sued a professional photography studio that refused to photograph the couple’s wedding. New Mexico law bars discrimination in “public accommodations” on the basis of sexual orientation. The studio said that New Mexico’s RFRA nonetheless barred the suit; but the state’s Supreme Court held that the RFRA did not apply “because the government is not a party.” Remarkably enough, soon after, language found its way into the Indiana statute to make sure that no Indiana court could ever make a similar decision. Democrats also offered the Republican legislative majority a chance to amend the new act to say that it did not permit businesses to discriminate; they voted that amendment down. So, let’s review the evidence: by the Weekly Standard’s definition, there’s “nothing significant” about this law that differs from the federal one, and other state ones—except that it has been carefully written to make clear that 1) businesses can use it against 2) civil-rights suits brought by individuals. . . The statute shows every sign of having been carefully designed to put new obstacles in the path of equality; and it has been publicly sold with deceptive claims that it is “nothing new.” Being required to serve those we dislike is a painful price to pay for the privilege of running a business; but the pain exclusion inflicts on its victims, and on society, are far worse than the discomfort the faithful may suffer at having to open their businesses to all.