Flannel trousers are the backbone of any tailored wardrobe. They’re professional without looking pushy, sophisticated without being slick. Best of all, while they’re perfectly suitable for the office, they make you feel like you’re lounging in your brushed cotton pajamas. Wool flannel is so soft and comfortable, the Brits used it for undergarments up until the early 20th century. Doctors even recommended wearing flannel to ward off ailments and cure dysentery. Although, not everyone was convinced. In a 1900 issue of The Medical Times, one skeptic wrote: “The writer was a constant victim to colds. He was really a victim of flannels, having fall after fall procured underwear of heavier weight and all wool, in the determination to avoid the chills and shivery sensations during winter. [He fell] for the flannel craze.”

Like all wool fabrics, flannel comes in two forms: worsted and woolen. Maybe these categories should be renamed to combed and uncombed, however, because it’s the combing process that separates them. Combing wool is exactly what it sounds like. Before wool is spun into yarn, a spinner can separate out the fibers by combing the material. This sets the hairs parallel to each other, as well as removes any of the shorter fibers that would spoil the regularity characteristic of worsted. After the wool has been combed, it’s spun into yarn and then woven into a fabric. And by combing the hairs first, the resulting fabric will feel a bit smoother and crisper, which is how you get shiny, hard-finished fabrics. Woolens, on the other hand, aren’t put through the same process. Thus, the fabric is spongier and loftier, as the fibers point in every possible direction. To give examples, gabardine is worsted; tweeds are generally woolen.

Flannel is available in both forms. Worsted flannel will have a subtle but visible twill weave just beneath its fuzzy nap. Woolen flannel, on the other hand, tends to look cloudier (like the every-which-way direction of the hairs on tweed). I prefer woolen flannel this time of year because it’s softer and spongier next to the skin, its lofty surface helps trap heat, and its mottled finish lends visual interest. None of these characteristics are present to the same degree in the increasingly more common worsted variety, whose only virtues are that it’s studier and can be woven into a lighter weight material. If you have the money for it, get worsted flannel for spring/ summer, then heavier woolen flannel trousers for those bitingly cold winter nights.

It’s almost a cliché nowadays to talk about the usefulness of gray flannel trousers. After a dark worsted suit and navy sport coat, they’re the closest you’ll come to a genuine wardrobe essential (at least if you rely on tailored clothing). Gray flannel trousers are a perfect foil for anything with which you wish to pair them – navy blazers, brown tweeds, and even tropical wool sport coats. The material is so good, Geoffrey Beene even has a fragrance named after it (Luca Turin gave it a rare five-star review in his book Perfumes, calling it “a masterpiece”).

Over the last couple of years, however, I’ve found I rely on flannel less and less. They’re still good, but I prefer the heavier rustic twills men used to wear when riding or hunting. Among these are cavalry twill, whipcord, and covert (the last two being nearly indistinguishable). These hang like iron, swing when you walk, and stretch where you need. And since they’re hard-twisted worsteds, they tend to hold their shape better than flannel, which can bag over time and require repressing.

In the first photo below, you can see my cavalry twill trousers, which were made by Tailor’s Keep in San Francisco from a cloth in Holland & Sherry’s Dakota book (a wonderful book for trouser fabrics, by the way). Cavalry twill gets its name from the British cavalry officers who used to wear the material as jodhpurs, a type of riding pant. It’s tightly woven, smooth, and clear finished, all of which means it’s hardwearing and wrinkle resistant. The material is like denim if denim could be made from wool and was magically more comfortable. And nevermind elastane-cotton jeans. The US government renamed cavalry twill elastique because of its stretch properties.

Cavalry twill is distinguished by its doubled twill weave (a twill within a twill), whereas covert and whipcord are single-line. Generally speaking, I find the second category to be a little more rustic and casual. Covert takes its name from its intended usage – clothes to be worn in the covert (produced “cover”), which is where hunters pursue game. Traditionally, finer fabrics risked getting snagged and ribboned by brambles and stray branches, which is why sportsmen favored covert cloth for their outermost layer. Today, it can be worn in the countryside or downtown. It often has a slightly mottled, flecked appearance that gives the coloring some visual depth.

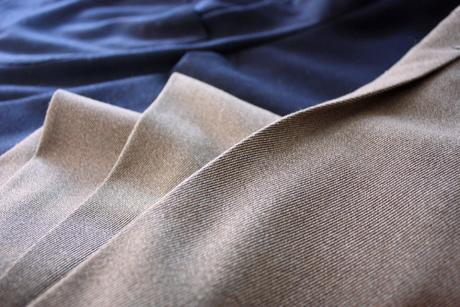

My oatmeal-colored pair, pictured in the second photo above, are made from whipcord, which looks nearly identical to covert cloth. Again, these were made by Tailor’s Keep from a Holland & Sherry fabric. (I’ll write more about Tailor’s Keep again in the future, but for those local to the Bay Area, I can’t recommend them highly enough for bespoke trousers. Ryan really knows how to make a good pair. And even if the prices are higher than when I first wrote about them, they’re a better value than Savile Row pants).

Like with a lot of traditional clothing, wool twill trousers can be a challenge to find today. As fewer men wear tailored clothes, many of the workhorse pieces that were once common in wardrobes have since disappeared – seasonal fabrics have been replaced by four-season cloth; casual suits have been supplanted by just dark worsteds; and aside from some generic single-breasted topcoats, dress outerwear is almost extinct. Today, you can find a million options for charcoal trousers in super thin Super 100000s wools, but you’ll struggle to find one good pair in a heavy rustic twill.

If you’re looking for a pair, try traditional clothiers such as O’Connell’s, Ben Silver, Cordings, New & Lingwood, and J. Press. Those will fit a bit full, as to be expected, but the quality of the fabric will be quite high. Brooks Brothers also carries them, notably in slimmer cuts, although the photos suggest they’re constructed from lighter weight materials. The best among the ready-to-wear options are likely going to be from Rota selection at The Armoury and No Man Walks Alone (the second of which is an advertiser on this site). Those will have a top-notch build and slightly slimmer leg line, while still being traditional enough to go with prickly tweeds, hopsack sport coats, and waxed cotton Barbours. Get your first pair of cavalry twill trousers in khaki, then whipcord in either tan, light brown, or mid-gray. Ones with more visible ribbing and mottling will feel sportier, which may pair well with earthier colors.

(photos via Voxsartoria, Sebastian McFox, The Armoury, No Man Walks Alone, Bernhard Roetzel, New & Lingwood, Douglas Cordeaux, and me)