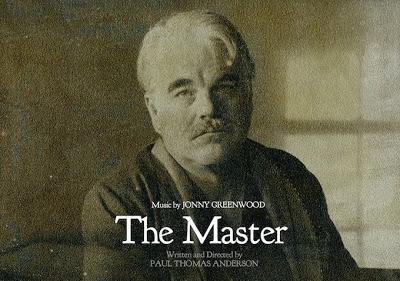

After wrestling with Paul Thomas Anderson's latest quandry "The Master" for nearly two months now, I'm certain about two things;

After wrestling with Paul Thomas Anderson's latest quandry "The Master" for nearly two months now, I'm certain about two things;While the film broaches a hefty blend of ideas that keep it thematically stout enough to haunt your dreams for days, it all boils down to a man's quest to find a love in his life. Rather, to find another love.

And as you know by now, Anderson tells Freddie Quell's story, in which the ex-Navy man/drifter and wanders aimlessly in and out of a drunken, psychosexual malaise until he lands in the bearish arms of Lancaster Dodd, the founder of The Cause, a trending religion of sorts paralleling what you and I know as Scientology.

The two take on an instant kinship for different reasons. 1) Simply put, they connect. They understand one another. 2) For Freddie, Lancaster and the Cause offer that unlikely acceptance he seeked on his path to nowhere. 3) For Dodd, Freddie is a project, one to which he can apply all the healing powers of the Cause to justify it to potential or non-believers.

But back to No. 2, Freddie's end. He bears the thematic weight of so much here, including a respresentation of post-World War 2 America and a particular ennui. Having suffered an unknown trauma prior to our meeting him, Freddie needs direction and solace. He can't or won't find either. His life before and during the war has set him up for failure and tragedy. Yet here he still stands.

Some say the film lets Freddie symbolize man as an animal. The argument is sound enough, given the weathered, hunched-over, near-disfigured veteran plays almost always to his animalistic instincts. He seeks sex, food and alcohol, in no particular order. That's how he'll survive in an ugly world that's managed to taken everything from him -- his mind, body and innocence.

I'll be specific. In between military tours, we see Freddie with a much younger woman, Doris, with whom he develops a relationship.

For me, "The Master" is movie is all about Doris. Freddie's "quest" is about finding again what he once had with Doris, the only substantive thing in his life. Dodd's kinship reminds him of that connection in some way, but I feel that relationship and The Cause are as temporary as his hooch or anything sexual.

Yes, sex is used as a tool in the film, but for Freddie I see it as more of an escape. In fact, I think Freddie's processing (aka "auditing" in Scientology) and other Cause applications meant to eradicate him of his troubled past lives or haunting memories only remind him of fonder days with Doris and reignite his feelings for her.

This is about love much more than it is about sex. Freddie had it, gave it up, regretted it, sought to recapture it, came close, preferred what he had before, sought it again, realized he lost it, went back for the other version, it was gone and was left with the memory of that substance with Doris (the sand lady that bookends the film).

It's simultaneously painful and beautiful. Or as one character says in Jim Jarmusch's "Down By Law," it is a sad and beautiful world. Thankfully, Freddie manages to find out the latter just in time.

The second lesson: If you're a leading man, you'll get your best performance under Anderson's direction. I'd argue you see the best work, to date, from Phillip Baker Hall, Mark Wahlberg, Tom Cruise, Adam Sandler, Daniel Day-Lewis and now Joaquin Phoenix in each of Anderson's films.

For some listed here, it's a no-brainer.

I don't know how Anderson communicates with these guys, what he specifically does on sets that unleash these furious and electrifying performances. Does it all start with the script? Are these characters so finely tuned and subtly painted that the actors simply sit in the driver's seat and hit the gas when he calls "action?" We know it's a collaboration, certainly.

But a coincidence? This, please, cannot be that. This is not just a matter of chance.

With Anderson, we've come to expect nothing less.

I'm reminded of a song he uses in the film, "Changing Partners" sung by Helen Forrest. Anderson has yet to use the same leading man, drifting from actor to actor, letting each veteran, seemingly established performer evolve beyond expectation under the watch of a still-young master in his own right.

A review by Ben Flanagan