First visit? Glad you're here! I hope you'll take a second to stop by my Facebook page and subscribe for updates so we can stay connected!

Follow

Follow

Let’s be real for a minute – we’ve all seen something we deem to be out of the ordinary and held our gaze on the sight just a bit too long. It’s human nature. And when it comes to people who have visible disabilities, we’re quite used to being on the receiving end of stares or double takes. While it can be frustrating, I try my hardest to consider a person’s stare as a moment of genuine curiosity rather than a display of rudeness. After all, despite being a passionate advocate for accepting everyone exactly as they are, even I have been the one guilty of staring on occasion. That being said, there’s a difference between expressing curiosity about disability and downright ogling that still seems to be lost on some people.

So, the announcement that the fourth season of Ryan Murphy’s American Horror Story will have a Freak Show theme reminded me that in certain, society has yet to move beyond perceiving disability as something unusual to be put on display. I know the season hasn’t started yet, so I can’t form a specific opinion, but I do feel some trepidation regarding the freak show concept. I sincerely hope Ryan Murphy is thoughtful about his portrayals of disability, because if he’s not, it’s quite possible to make disabilities seem even more freakish and frightening to the general public than they already are. Conversely, if done well, the freak show theme has real potential to open up important conversations and challenge conventional ways of thinking about disability.

My concerns are perhaps heightened due to my recent visit to the Ripley’s Believe It or Not “Odditorium” in Times Square in New York City. It’s a total tourist trap, but for the most part, it made for a entertaining afternoon with my friend Julia. However, the disability activist within me struggled with the ableist and discriminatory mindset that was so deeply intertwined with some of the museum’s exhibits.

Essentially, the Odditorium relies on the stigma against disability that has historically influenced society’s perceptions in order to create shock value and evoke strong reactions from patrons. Granted, Ripley’s Believe It or Not was at one time an actual show that originated in the early 1900s, a time when exploitation of physical difference for the sake of amusement and monetary gain was considered socially acceptable. Freak shows were a common form of entertainment back then that involved “normal” people gawking at people with obvious physical differences. So, even though the Odditorium is reflecting history, it’s clear that the exhibits make no effort to negate this antiquated freak show theme.

Instead, the Odditorium has an eerie feel of giving its visitors complete permission to slip back into the mindset of outdated disability stereotypes in ways that would be considered unacceptable in other contexts. Barely five minutes into the visit, Julia and I encountered the first of many examples of disability on display: a wax figure of a man named Johnny Eck, who actually was a freak show performer for part of his career. The figure prominently shows that his body ends mid-torso. I was rather uncomfortable with the idea that this figure was display worthy because of his disability, but all of the people around me were absolutely fascinated – laughing, pointing, and mocking. Next to Eck’s figure was an interactive optical illusion that allowed people to appear as though the bottom half of their body had gone missing. I admit that Julia and I were amused by how well the illusion works. But, we enjoyed it purely for the sake of the illusion.

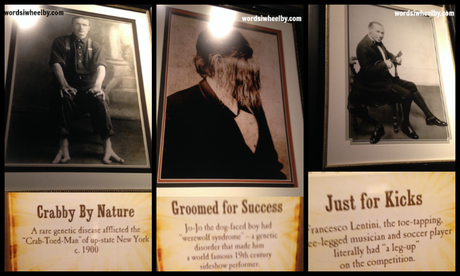

The whole point of the museum is giving people a chance to gawk, and heck, I even paid for a ticket to do so. Yet, combining displays about “abnormal” human beings with displays ranging from medieval torture devices to baseball artifacts just doesn’t make sense to me. Even so, as we continued to venture through the museum, we saw several more instances of human “freak” exhibits, including pictures, statues, and videos. I was particularly struck by a series of black and white photographs that showed people who were actually part of the Ripley freak show. Nowhere did the exhibit specify that people should not make fun of or judge people with visible physical disabilities as was done in the early 20th century. In fact, the pictures had captions with rather tasteless jokes posted underneath them. To me, the attempts at humor just fell flat, instead driving home the ableism. I fear that to many other visitors, it likely reinforces a message that it is okay to mock disability and to objectify humans simply because they look different. Not enough distinction was made to indicate that the exhibit is intended to reflect history, and not 2014.

Like it or not, we cannot deny that the degradation of the disability community through freak shows happened. And unfortunately, messages and images like this that perpetuate the idea of disability as freakish can still be pretty easily found in the media. I worry about the possibility that the same sort of freak show negativity could overtake the entire fourth season of American Horror Story. If this happens, it could be a huge step backwards for portrayals of disability in the media, especially because the show is so popular.

In the case of Ripley’s Odditorium, I don’t have much hope that they would consider recontextualizing their exhibits because the fact remains that it houses history. But, I have very high hopes that American Horror Story won’t perpetuate stereotypes, and will instead do justice to the incorporation of disability within the story line. Ultimately, it’s crucial for the consumers of such forms of media to understand that the freaks at which they gawk are representative of visibly disabled people who exist in the real world. We’re humans, not just plot devices to be objectified for your entertainment.

Image descriptions:

1) (From left to right:) Wax figure of Johnny Eck, a man born with no torso, next to a picture of my friend inside an optical illusion making it appear she has no torso.

2) (From left to right:) A photograph of a man with hands and feet that are thought to look like crab claws. Caption reads “Crabby By Nature – A rare genetic disease afflicted the ‘Crab-Toed-Man’ of up-state New York c. 1900.” Next, a photograph of a man with a lot of hair covering his face. Caption reads “Groomed for Success – Jo-Jo the dog faced boy had ‘werewolf syndrome’ – a genetic disorder that made him a world famous 19th century sideshow performer.” Next, a photograph of a man with three legs. Caption reads “Just for Kicks – Francesco Lentini, the toe-tapping, three-legged musician and soccer player literally had a ‘leg-up’ on the competition.”

Like what you read? Subscribe for weekly updates and be sure to confirm your e-mail!