What is it Like to Be a Bat?” was a seminal paper by philosopher Thomas Nagel. Implying bats experience their battiness. Like we experience our own existence. How does that work? David Hume said introspection can’t tell us; I’ve tried endlessly, and it’s true. One cannot use the self to probe the self.

My humanist book group is tackling Anil Seth’s Being You, yet another stab at demystifying consciousness. We know a lot about how the brain works, consisting of neurons, extensively interconnected, processing signals, and regulating behavior. We understand pretty well, for example, how visual signals enter the brain and get processed into images one sees. But those last two words embody what’s been called “the hard problem” of consciousness. Who or what does that seeing? How does that neuronal functioning give rise to what we experience as personhood?

Seth harks back to earlier scientists struggling over the question what is life? Even while knowing quite a lot about living things, what makes them “alive” still seemed a hard problem. They spoke of some mystical elan vital or “life force,” that wasn’t understood and maybe never could be. But that problem gradually went away as science grew to better understand the underlying processes, so that today nobody asks any more what makes something alive. And Seth foresees the same thing eventually happening with the hard problem of consciousness.

Thus he writes in terms of what he calls “the real problem.” Not seeking some “eureka” insight explaining consciousness in one neat formulation. Instead — just as science grew to understand, bit by bit, what life is —we’ll demystify how the various manifestations of consciousness map onto physical brain activity, “to build increasingly strong explanatory bridges between mechanisms and phenomenology.”

Perception is central to the problem. Consciousness and the self are all about experiencing and making sense of perceptions of the outside world and also, importantly, what’s happening inside us. That, once more, raises the question of who or what does the experiencing — and how. Taking vision again, it might seem as if there’s a little man inside our brain viewing a screen on which visual signals are projected (the “Cartesian Theater”). Nothing like that is true.

So how do we make sense of perceptions? When it’s raining, of course the brain isn’t wet. Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio posits that the brain creates a representation, like an artist’s picture, of the raining. But also needed is a perceiver — the self, which Damasio says is another representation the brain makes. And it also needs yet a third level representation, of the self doing the perceiving.

Seth’s take is somewhat different, writing of perception as “controlled hallucination.” From the signals, the brain constructs its Bayesian “best guess” of reality. And the aim is not representational accuracy but rather utility in terms of what best enables us to function. We must “understand perception as an action-oriented construction, rather than as a passive registration of an objective external reality.” (“Hallucination” seems an unfortunate word choice, connoting seeing something not there at all.)

Seth writes that “the self is itself a perception, another variety of controlled hallucination.” The mind’s role as part of a living system is crucial. It’s all really about keeping that system going. Seth calls this his “beast machine” theory.

He casts moods and emotions as arising from perceptions. For example, if you see a bear, you feel fear. But, says Seth, what your brain actually perceives is not some picture of what the bear could do to you but, rather, your bodily sensations — heart rate rising, muscles tensing, etc. This seems backwards, ignoring what caused those bodily changes in the first place — the brain’s imagining what could happen, to which your body responds.

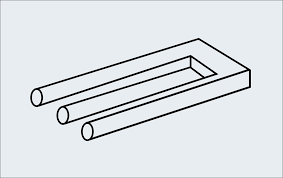

This points up a more fundamental problem with Seth’s approach. He also brings in optical illusions as showing how perception and reality can differ, again arguing that reality is something our brains create.

I instead believe in the reality of reality. The threat of a bear is no mere brain “hallucination” or construction; and while optical illusions can flummox our perception systems, those are rare, and mostly what we see is really there. Seth’s dichotomy between accuracy and utility is nonsense. If our brains weren’t extremely good at representing a true reality, we’d quickly die.

But digging down deeper, Seth goes on to query what it means for an organism — or anything — to exist.* He says this requires a boundary between it and everything else. Living things must maintain that over time, fending off the Second Law of Thermodynamics and its associated entropy rise. And this, Seth writes, requires “occupying states which it expects to be in” (his emphasis). Which brings in neuroscientist Karl Friston’s “free energy principle” — free energy equates to “prediction error,” the gap between the brain’s expectations and actuality, which must be minimized. By actively working at that, living systems “will naturally come to be in states they expect — or predict — themselves to be in.” And this, Seth seems to posit, is the nub of consciousness — “I predict myself, therefore I am.”

Circling back to his “hallucination” concept, Seth says the “hard problem,” implying “that the conscious self is somehow apart from the rest of nature . . . turns out to be just one more confusion between how things seem and how they are.” He also writes of consciousness as “the perceptual expression of a deep continuity between mind and life.”

This sounds like spinning mysticism, no help on the “hard problem.” Seth is talking in metaphors with no clarity on what the metaphors represent, because that defies being stated.

Let’s not forget that the problem is how neuronal functioning gives rise to what one experiences as the self. It is a mechanistic problem. And in the end Seth seems to acknowledge this. Saying his construct is not really a theory of consciousness but rather a theory for consciousness science — to point the way for tackling the hard problem.

So Seth does not (of course) claim to solve it, and his final line deems it “not so bad if a little mystery remains.” A little! But I would still love to understand what it’s like to be me.

* The very concept of existence is indeed philosophically problematic. I’ve written about this, using the term “isness” to denote the fundamental quality of existing, while also arguing that it’s actually impossible. Though readers of my essay (https://rationaloptimist.wordpress.com/2021/12/06/isness-what-is-existence/) did not seem to realize it was a tongue-in-cheek parody.