How would you like to spend your last days in a nursing home? In a tiny cubicle with no privacy, no autonomy, no possessions, everything gone that made life worth living, surrounded by people who . . . well, you know.

How would you like to spend your last days in a nursing home? In a tiny cubicle with no privacy, no autonomy, no possessions, everything gone that made life worth living, surrounded by people who . . . well, you know.

Dr. Atul Gawande’s book, Being Mortal, addresses such end-of-life issues. It’s very relevant for me. My mother-in-law, 86, was in “assisted living” but a recent series of falls messed her up.

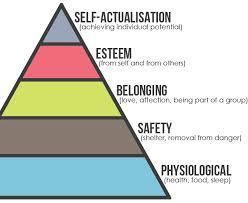

At one point Gawande notes psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of human motivations, crowned by mastery of knowledge and skills, gaining reward for achievement, and “self-actualization.” But he observed that aging people tend to narrow their concerns, concentrating more on family and friends. Why the change? Gawande acknowledged several theories – but I instantly knew the answer, because even while at 68 I remain very on-the-go, my perspective on life has changed.

So the pleasures of the moment are more important than Maslowian self-actualization. How many more cookies will I get to eat?

One thing that struck me – as it did Gawande – is the degree to which an exaggerated concern over safety dominates and constrains the circumstances in which elderly people exist. (I didn’t say “live” because, as Gawande shows, for too many it really isn’t living). And the safety concern is not so much on the part of the elderly themselves, as it is their children and caregivers (and of course the latter have a big concern to avoid blame for an adverse outcome).

The mentioned change of perspective is relevant. It’s tragic to die with “your whole life ahead of you.” At ninety, not so much. The concerns are different. But putting oldsters in a safe environment often means restricting what they can eat, what they can do, what activities they’re permitted, etc. They are made prisoners of safety. Gawande says they’re given “a life designed to be safe but empty of everything they care about.”

That perspective seems missing from eldercare. As though the safety obsession will keep folks from dying. When in fact, at best, it will only keep them alive for what is really a relatively short time. I daresay many elderly people would accept a small risk of dying a little sooner in exchange for more freedom and autonomy – more quality of life – while it lasts. There’s not much value in a longer life if it’s “lived” as described in my opening paragraph.

After all, the point of living is not just to not die. It certainly isn’t to not die tomorrow rather than the day after.