Almost four years ago I’d done a post about the possibility that King Kong (1933) has ring-from composition [1]. In that post I mentioned that David Bordwell had tipped me off to the possibility, following a presentation he’d seen by Thierry Kuntzel and I appended a passage from a 1976 article by Judith Mayne in which she remarked upon the symmetries in the film [2]:

And yet the structure of King Kong is a paragon of symmetry. The center of the film, occurring on Skull Island, is enclosed by two sequences occurring in New York, and these two sequences in their turn are enclosed by the references to Beauty and the Beast. (377)I have now, at long last, taken a look myself and have tentatively concluded that, yes, King Kong is a ring form text. The symmetry is certainly very strong and my reservations are details, though worth thinking about.

First things first. As far as I know there’s only one DVD reissue, by Warner Home Video (2005) and that’s what I’m working from. All timings are from that DVD.

Preliminary ring-composition analysis

The original 1933 King Kong, directed and produced by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, entered the National Film Registry in 1991 and has been remade twice, in 1976 and 2005 [3]. It received rave reviews at its original release. The review aggregator, Rotten Tomatoes, has ranked it the fifth greatest horror film of all time [4] and the 29th greatest film of all time [5]. I rather imagine that the Rotten Tomatoes rankings fluctuate quite a bit – the film was rated higher in both lists in the Wikipedia article, which accessed them on March 17, 2010 (horror, when Kong was 1st) and October 14, 2016 (all time greatest, when Kong was 20th) – so we should take those rankings with a grain of salt, but only a grain. The film certainly merits careful examination.

King Kong is something of a film-within-a-film. Carl Denham, a maker of adventure films, has the idea for the film of a lifetime. He recruits Ann Darrow, whom he’d found stealing a piece of fruit at a street side stall, to star in it. They travel to Skull Island, where the filming is to take place, and does. During the voyage Darrow falls in love with Jack Driscoll, the first mate on the ship. The natives on the island offer Darrow to Kong, who takes her into the interior of the island. She’s rescued, and Kong himself is brought back to New York where he’s exhibited on Broadway. He escapes, takes Darrow up the Empire State Building, where he’s killed. Darrow, presumably, lives happily ever after with Driscoll.

Here’s the basic form of the action:

1 Start in New York City where Carl Denham recruits Ann Darrow for his film.

2 We journey to Skull Island and land near a village where the inhabitants worship Kong.

X Then we move through the village into Kong’s territory, where Kong takes Darrow.

2’ Darrow is rescued and we return to the village, followed by Kong who goes on a rampage and is finally subdued on the beach by gas.

1’ We return to New York City where Kong is put on display, escapes, takes Darrow up the Empire State Building, and is killed.

That seems symmetrical enough, which is the main requirement for ring-composition. However, in the first half we spend eight minutes on board the ship traveling from New York City to Skull Island. But in the second movement we cut directly from Skull Island to New York. Do we count that as a failure of symmetry, and is that failure bad enough that we cannot count King Kong as a ring-form text? I’m not sure, but for the moment I want to set that question aside. I’ll return to it at the end.

There’s a more pressing issue, one that takes us deeper into the film. The film runs roughly an hour and 43 minutes from the opening to the final display of credits, though the first four minutes is given over to an overture with nothing on the screen but a card that says “Overture”. The central section, when we’re in Kong’s territory, is a bit over 28 minutes long, which strikes me as being a bit long to be the turning point in a film that runs almost one and three quarter hours. Is there, within that section, a shorter segment that serves as the turning point?

I believe there is, and it’s a battle between King Kong and a T-Rex. It is almost four minutes long and is, I believe, the longest and most complex single fight sequence in the film. (I haven’t actually checked the timing on the others. I’m just guessing about this.) Given that, at this point in the film, the goal is to rescue Darrow from Kong, you’d think that the moment of rescue would be the center point. But I don’t think that’s right. The timing’s off.

The film is roughly 01:43 long and the T-Rex fight starts at c. 1:01:51, well over half-way through. The rescue sequence starts at roughly 1:14:03, which is over two-thirds of the way through the film, and it only lasts for about two-and-a-half minutes (1:14:03-1:16:38 or so), making it shorter. For those reasons, position in the film and relative length (and thus prominence) of the two sequences, I think the T-Rex fight is the center point.

That gives us:

1 Start in New York City where Carl Denham recruits Ann Darrow for his film.

2 We journey to Skull Island and land near a village where the inhabitants worship Kong.

3 Then we move through the village into Kong’s territory, where Kong takes Darrow.

X Kong battles T-Rex.

3 Driscoll (ship’s mate) finally frees Darrow from Kong.

2’ Darrow is rescued and we return to the village, followed by Kong who goes on a rampage and is finally subdued on the beach by gas.

1’ We return to New York City where Kong is put on display, escapes, takes Darrow up the Empire State Building, and is killed.

What is Kong? Who is Kong?

And it also gives us much to think about. Darrow’s rescuer, Jack Driscoll, the ship's mate and husband-to-be, is nowhere to be seen in that central sequence. He’s in a shallow cave beneath the edge of a cliff where he’d gone to escape Kong, and where he’d wounded Kong in the hand with his knife.

01:01:01 – Driscoll stabs Kong

01:01:01 – Driscoll stabs Kong

Kong is distracted from dealing with Driscoll when he hears Darrow’s screams in response to the T-Rex.

01:01:43 – T-Rex (background) threatens Darrow

01:01:43 – T-Rex (background) threatens Darrow

Darrow watches the battle from the trunk of a dead tree where Kong had previously placed her.

01:04:53 Darrow watches Kong fight T-Rex

01:04:53 Darrow watches Kong fight T-Rex

The tree is knocked over in the course of the battle, pinning Darrow to the ground.

01:03:51 Darrow trapped under tree

01:03:51 Darrow trapped under tree

Kong releases her from the tree once he’d killed the T-Rex. He takes her to his lair.

01:05:21 Kong takes Darrow to his lair

01:05:21 Kong takes Darrow to his lair

Meanwhile Driscoll climbs up out of his cliff-side hiding place and reconnects with Denham. Then he checks out the slain T-Rex and follows Kong.

The first thing to note is that Kong is thus quite a different kind of giant beast from Gojira in the original Japanese film (Gojira 1954). Gojira goes on a rampage against Tokyo and that’s pretty much it. Many people die, of course, but that’s a general consequence of the rampage. Gojira doesn’t target specific individuals. Kong will do so a bit later in the film. But Kong also spends a good deal of time and effort fighting other creatures, all of them dinosaurs, in addition to humans. In this particular scene he was, after all, rescuing Darrow from T-Rex.

Moreover, though Kong is huge, powerful, and violent, and Darrow is quite right to be scared out of her wits at having been captured by him, she does not ever appear to have been in danger from him. To be sure, once he’s taken her back to his lair, he rips part of her dress off

01:12:59 Kong rips off a piece of Darrow’s dress

01:12:59 Kong rips off a piece of Darrow’s dress

examines the piece of fabric

01:13:03 Kong examines piece of dress

01:13:03 Kong examines piece of dress

prods her

01:13:14 Kong prods Darrow

01:13:14 Kong prods Darrow

and then sniffs his finger.

01:13:18 Kong sniffs his finger

01:13:18 Kong sniffs his finger

But she appears to be all right. Frightened, but not physically harmed.

01:10:26 Darrow’s OK (sorta’)

01:10:26 Darrow’s OK (sorta’)

She attempts to escape his grasp

01:13:37 Darrow struggles in Kong’s grasp

01:13:37 Darrow struggles in Kong’s grasp

he tickles her breasts

01:13:47 Kong tickles her breasts

01:13:47 Kong tickles her breasts

and she continues to struggle. More tickling (with appropriate twittery woodwind sounds in the music) and more finger sniffing:

01:13:59

01:13:59

The whole scene, which, for obvious reasons, was cut from subsequent releases [1], is bizarrely playful: Kong is curious and playful; Darrow is frightened. The combination is bizarre.

Meanwhile Driscoll approaches and knocks a boulder down.

01:14:07 Driscoll Knocks over a boulder

01:14:07 Driscoll Knocks over a boulder

The noise alerts Kong and he sets Darrow down and goes after Driscoll:

01:14:22 Kong goes after Driscoll

01:14:22 Kong goes after Driscoll

See him there at the lower left, about a quarter of the way up from the bottom?

And then, you know what? A pterodactyl arrives and grabs Darrow:

01:14:53 Grabbed by a pterodactyl

01:14:53 Grabbed by a pterodactyl

Now Kong has to rescue her again. Which he does. Once he’s set her down he continues fighting with and killing the pterodactyl. Meanwhile Driscoll manages to rescue Darrow.

What are we to make of all this? There would appear to be something sexual going on between Kong and Darrow, but just what, given their differences in size, could that possibly be about? What it’s about obviously, is the audience that’s watching – the male gaze in full flight, as it were.

But let’s set that aside for now. I’m not going to try to explain it, at least not in this post. I’m just pointing out that it happened, and that it is really quite strange.

There’s one more thing I want to point out, and that’s near the end of the film. By this time we know that Darrow and Driscoll are to be married (and live happily ever after?). Kong is put on stage, becomes frightened at the photographers’ flashes, and he escapes. In the course of his escape he recaptures Darrow and takes her to the top of the Empire State Building, which had been completed quite recently (1931). Just why did he take Darrow? Had he become attached to her?

When you’re watching the film you don’t ask questions like this. Things move too fast. But when you’re sitting back and stepping through it scene by scene, even frame by fame, the questions just pile up.

Again, I’m not going to attempt to answer them. I’m just laying some material out for later consideration. Whatever’s going on – Kong, Darrow, the sniffing, the dinosaurs, not to mention those natives who were the ones who offered Darrow to Kong in the first place, we haven’t even discussed them – whatever it is, it’s in the realm of myth logic, as I’ve come to call it (thinking of Lévi-Strauss). Myth logic doesn’t make much sense, but there’s an order to it.

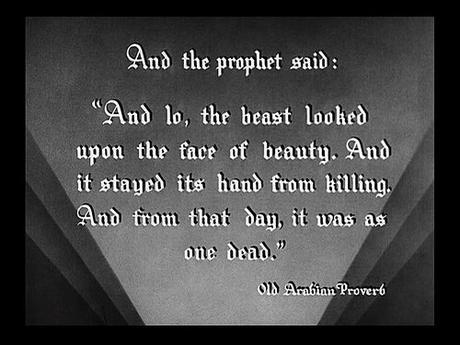

This particular bit of myth logic is framed by the trope of Beauty and the Beast, as Judith Mayne pointed out over four decades ago. Immediately after the opening credits we see this frame:

00:05:58

00:05:58

Then, at the very end of the film when a crowd has gathered around a fallen Kong, a policeman remarks (c. 1:43:33): “Well, Denham, the airplanes got it.” He replies: “Oh no. It wasn’t airplanes. It was beauty killed the beast.”

01:43:31 Kong is dead

01:43:31 Kong is dead

01:43:42 Denham philosophizes

01:43:42 Denham philosophizes

Denham repeats the trope several times during the film, most prominently while aboard the ship traveling to Skull Island. He remarks to Driscoll, the mate (c. 19:25):

It’s the idea for my picture. The Beast was a tough guy, too. He could lick the world. But when he saw Beauty, she got him. He went soft, he forgot his wisdom, and the little fellas licked him. Think it over, Jack.After the initial landing on Skull Island they return to the ship. It’s then that Driscoll discovers that he had fallen in love with Darrow. Notice his confession of fear in the course of his declaration (c. 36:44):

Jack: When I think what might have happened today – if anything’d happened to you. Ann: Then you wouldn't be bothered with a woman on board. Driscoll: Don't laugh. I'm scared for you. I'm sort of - I'm scared of you, too. Ann, uh um Iya ah say -- I guess I love you. Ann: Why Jack! You hate women! Driscoll: Yeah, I know. You aren't – women. Hey ah Ann, I don't suppose ah I mean – you don't feel like this about me – do you?They kiss:

00:37:39 Driscoll kisses Darrow

00:37:39 Driscoll kisses Darrow

Just how seriously are we to take this trope? Given the explicit emphasis that Cooper and Schoedsack have given it – it appears in at least one other place in the film, when Denham is talking to reporters at Kong’s unveiling on Broadway – I’d say they’re pretty serious about it. For one thing, it’s consistent with the ending. It is Kong, not Darrow, who ends up dead. And it helps explain why Kong sought her out when he escaped his chains in New York and, for that matter, it also helps us understand that strange scene when Kong is playing with her after he had defended her from the T-Rex.

But it also plays against the fear that people in the film, most obviously Darrow, experience in Kong’s presence. He IS a huge, powerful and violent beast. How could he be threated by a mere human female? Add to that the fact that this is a film about the making of a film and we have plenty of room for the play of myth logic.

Let’s just set all that aside for now – we can take it up again in a later post. I want to return to the ring composition analysis.

The ring composition in more detail, with some remarks on method

Here’s a table showing the ring-form structure along with more detail about what happens and when. I’m just going to put the table here and, except for a methodological remark, save discussion for later.

1New York City [00:06:06]

Carl Denham sees Darrow attempting to steal an apple. He pays the fruit seller and recruits Darrow to his film project, assuring her that there’s no sexual favors involved: “What do I have to do?” “Just trust me and keep your chin up.”

Aboard Ship [00:14:19]

Denham and Darrow board the boat to Skull Island. She meets Jack Driscoll on the ship, where he’s first mate. He’s never been on a ship with a woman before. Denham does a screen test of Darrow. She’s wearing a diaphanous dress. Denham urges her to scream for her life. The test is observed by Driscoll & some sailors.

2Arrive on Skull Island [00:24:33]

Leave the ship and go to a native village where they observe a ritual in which a young woman is to be offered to Kong. Return to the ship. Driscoll & Darrow declare their love. Darrow is kidnapped off the ship, taken to the village, and offered to Kong, who is kept behind a big wall.

3Into Kong’s Territory [00:49:08]

Kong takes Darrow deep into his territory. Men from the ship follow him. They kill a Stegosaurus and some are killed by Brontosaurus.

XKong vs. T-Rex [01:00:34]

He fights and kills T-Rex. At the beginning of the fight she’s up in the trunk of a dead tree, which is knocked over in the fight. She’s unhurt. Kong takes her back to his lair, high on a cliff. He’s distracted by a pterodactyl and Driscoll rescues her.

3 Driscoll & Darrow back through the wall. [01:18:02]

Driscoll & Darrow make it back through the wall and into the village. Kong follows, killing villagers. He’s gassed unconscious on the beach.

2NYC: “Kong, Eighth Wonder of the World” [01:24:36]

Kong’s put on display on a Broadway stage. He’s frightened by flashbulbs going off and escapes, rampaging through NYC, destroying a subway train, and recapturing Darrow.

1On the Empire State Building [01:37:41]

He climbs the Empire State Building with Darrow. Sets her down and fights the airplanes sent to kill him. They kill him and he falls to the ground. Darrow and Driscoll are reunited. Denham: “It was Beauty killed the Beast.”

The methodological remark is about what’s going on in this kind of analysis and why I’ve set aside the asymmetry I mentioned above. Notice, first of all, that I’ve indicated that asymmetry in the table (the gray section, “Aboard Ship”). There is no ocean sequence in the second half to balance the structure.

Does that disqualify King Kong from being a “true” ring-composition? In his 1976 review of the ring-composition literature in literary criticism, R. G. Peterson noted that there was some question as to whether or not these structures existed in the texts, or where placed there by critics [6]. That question always arises in literary criticism, and it was under particularly heavy debate at that time. But Peterson was clearly sympathetic. James Paxson, on the other hand, is not at all sympathetic to ring composition – dismissively terming its critics “ringers” – in his ‘deconstructive’ 2001 discussion [7].

And yet, it seems to me that the film’s structure has an unmistakable symmetry about it. As I indicated at the beginning of this post, two critics have already noted that symmetry, Thierry Kuntzel and Judith Mayne, even if they haven’t explored it systematically. I have no investment in exact symmetry. Approximate symmetry seems to me remarkable enough. I’m interested in what is there. The only way to determine what’s there is through careful analysis, but also comparative analysis. Do we find such symmetries in other texts? Are they exact or only approximate?

Such analytic and descriptive work is also communal. It is not enough that I think the film is symmetrical – and, remember, I only went looking because other critics had already suggest that King Kong is symmetrical. Other critics must examine the film as well. But those critics have to be sympathetic to the work. It is clear that Paxson rejects the possibility of symmetry [8]. Critics have become comfortable enough with ‘hidden’ features that are disruptive (the psychoanalytic unconscious) and coercive (capitalism, patriarchy, racism), but the idea of hidden order is strange and no doubt threatening.

And that is what we find in ring-composition, rigorous order that is not apparent to casual inspection. What is that order but a manifestation of the creative powers of the human mind?

References

[1] Ring Form Opportunity: King Kong – and some notes on how to do it, New Savanna, accessed September 29, 2017, http://new-savanna.blogspot.com/2013/12/ring-form-opportunity-king-king-and.html

[2] Judith Mayne, “King Kong” and the Ideology of Spectacle, Quarterly review of film studies, Vol. 1, No. 4, November 1976: 373-387.

[3] King Kong (1933 film), Wikipedia, accessed October 2, 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_Kong_(1933_film)

[4] Top 100 Movies of All Time, Rotten Tomatoes, accessed October 2, 2017, https://www.rottentomatoes.com/top/bestofrt/top_100_horror_movies/

[5] Top 100 Movies of All Time, Rotten Tomatoes, accessed October 2, 2017, https://www.rottentomatoes.com/top/bestofrt/

[6] R. G. Peterson, “Critical Calculations: Measure and Symmetry in Literature”, PMLA 91, 3, 1976: 367-375.

[7] James J. Paxson, Revisiting the deconstruction of narratology: master tropes of narrative embedding and symmetry. Style, Vol. 35, No. 1 Spring 2001, 126-150.

[8] I point this out in a short blog post, Once more, with feeling: Computation, criticism, and a way forward, New Savanna, blog post, September 4, 2017, https://new-savanna.blogspot.com/2017/09/once-more-with-feeling-computation.html