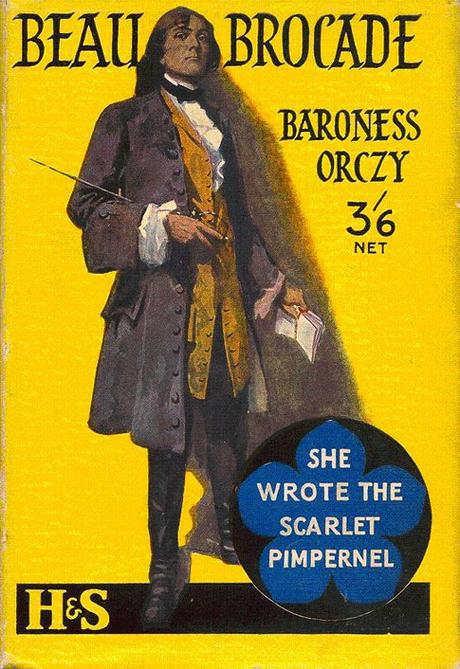

Book review by George Simmers. This month we are looking at books and writers connected with Derbyshire and Yorkshire, and this novel, despite being written by the Hungarian, Baroness Orczy, qualifies on both counts. It is set on the moors of Derbyshire, and Baroness Orczy, having married her theatrical collaborator, Montagu Barstow, lived with him in his home county of Yorkshire.

Beau Brocade is a historical extravaganza set just after the unsuccessful Jacobite rising of 1745. Bonnie Prince Charlie’s troops had made it as far south as Derby before retreating back to Scotland. English soldiers are scouring Derbyshire for those who helped the Jacobite cause, and have a warrant for the young Earl of Earl of Stretton, although he is innocent. A local squire, the vile Sir Humphrey Challoner wants to turn this to his advantage, since he has designs on Stretton’s beautiful sister, Lady Patience Gascoyne. The price of his help will be her hand in marriage.

The Derbyshire moors are bleak and gaunt, and we a reminded that they are the location of ‘the old gallows, whereon many a foot-pad or sheep-stealer had paid full penalty for his crimes.‘ Luckily, these desolate moors are also the home of Beau Brocade, a gentleman highwayman who steals from the rich and gives to the poor (of course he does, he’s the hero of a baroness Orczy novel.). He is a man of mystery, as the local beadle explains:

Nay, no one has ever seen his face, though his figure on the Moor is familiar to many. He is always dressed in the latest fashion, hence the villagers have called him Beau Brocade. Some say he is a royal prince in disguise—he always wears a mask; some say he is the Pretender, Charles Stuart himself; others declare his face is pitted with smallpox; others that he has the face of a pig, and the ears of a mule, that he is covered with hairs like a spaniel, or has a blue skin like an ape. But no one knows, and with half the villages on the Heath to aid and abet him, he is not like to be laid by the heels.

In fact he is none of these, but Captain Jack Bathurst, an officer unfairly cashiered from the Army and now turned Byronically to crime. He is swashbuckling, brilliant and noble, and as soon as he sees Stretton’s sister he falls utterly in love with her, and she, of course, falls in love with him at first sight, even though he’s wearing a mask.. His daring stratagems save the young Earl’s life a couple of times, and she yearningly reciprocates his love, but the evil Sir Humphrey has other plans. There are letters that prove Stretton is no rebel, and the ungentlemanly Sir Humphrey wants to use these as a bargaining tool, offering them to the,lovely Lady Patience on condition that she will marry him, to save her brother from hanging.

The novel is packed with action and romance and is wonderfully fast-moving. Like The Scarlet Pimpernel of a few years earlier, Beau Brocade began as a stage play (written in 1905, but not produced till 1908, after the appearance of the novel). Some scenes are wonderfully stagey, with sudden turns in fortune, amazing revelations of disguise and terrific exit lines. Even in 1907 it must have seemed a rather old-fashioned play, though, since it contains all the stock ingredients of traditionL Victorian melodrama: the blacksmith is strong and loyal; the lawyer is wicked and scheming; the beadle is pompous; the yokels are gormless; the heroine is plucky , and the villain is villainous to the core, with not one single redeeming feature. There is not one original character in the whole book; even Beau Brocade is just a variation on the legendary Claude Duvall, an elegant highwayman famous for claiming a dance from the beautiful ladies whom he robs; Beau Brocade does likewise. There are also one or two scenes that are direct cribs from Shakespeare.

Despite this utter lack of originality, the book is immensely enjoyable. The twists and turns of the characters’ fortunes come thick and fast, and this reader for one always wanted to know what was coming next. The copy I read was published by Hodder and Stoughton in 1953, fifty years on from first publication – a good innings for what cannnot have been much more than a pot-boiler.

The book is not unlike Orczy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel, has not made its mark on the popular imagination that the earlier book did. In the French Revolution Orczy found a subject exactly suited to her purposes, and one that had not been very much exploited fictionally before, except in Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, and its theatrical adaptation The Only Way. The aftermath of the Jacobite rebellion was not such a fruitful subject for her. I don’t think she ever returned to th theme.

It won’t really be a spoiler if I tell you that the book has a happy ending, with justice triumphant. What is maybe interesting is that the resolution is produced by the Duke of Cumberland, brother of King George II, and indeed the man responsible for clearing up after 1745. But a historical purist might wonder at the presentation of him in this novel as the kind and generous distributor of justice. The historical duke was known as Butcher Cumberland, and was responsible for war crimes like the massacre after Culloden. But then Baroness Orczy never was writing for historical purists.