In addition to the surpassing coolness of reconstructing long-gone ecosystems, my new-found enthusiasm for palaeo-ecology has another advantage — most of the species under investigation are already extinct.

In addition to the surpassing coolness of reconstructing long-gone ecosystems, my new-found enthusiasm for palaeo-ecology has another advantage — most of the species under investigation are already extinct.

That might not sound like an ‘advantage, but let’s face it, modern conservation ecology can be bloody depressing, so much so that one sometimes wonders if it’s worth it. It is, of course, but there’s something marvellously relieving about studying extinct systems for the simple reason that there are no political repercussions. No self-serving, plutotheocratic politician can bugger up these systems any more. That’s a refreshing change from the doom and gloom of modern environmental science!

But it’s not all sweetness and light, of course; there are still people involved, and people sometimes make bad decisions in an attempt to modify the facts to suit their creed. The problem is when these people are the actual scientists involved in the generation of the ‘facts’.

As I alluded to a few weeks ago with the publication of our paper in Nature Communications describing the lack of evidence for a climate effect on the continental-scale extinctions of Australia’s megafauna, we have a follow-up paper that has just been published online in Proceedings of the Royal Society B — What caused extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna of Sahul? led by Chris Johnson of the University of Tasmania.

After our paper published earlier this month, this title might seem a bit rhetorical, so I want to highlight some of the reasons why we wrote the review.

At risk of sounding a bit like a broken record (I wonder if the Millennials understand the meaning of that expression), the complex interplay of changing climatic conditions and the sudden appearance of an extremely efficient predator (humans) is likely to have operated rather differently around the world. This is because the variation in the intensity, velocity and type of climatic changes coupled with the variation in the intensity and efficiency of human hunting, would have resulted in many different synergies over the last several hundred thousand years of the great human expansion. In some places, you find evidence of some climatic signal, and in others, none at all.

The biggest problem is the quality of the data, because we are talking about prehistoric sleuthing here. We have nothing at our disposal but the fossilised remains of species, ancient DNA signatures, layers of pollen and big-animal shit fungus in lake sediments, layers of trapped gas in ice cores, coral growth patterns, and tree ring data with which to construct entire ancient ecosystems. It’s a bit like geologists studying the chemical composition of a rock they find on the side of a volcano and making inferences about the composition of the Earth’s core (i.e., difficult and at best, massively indirect).

When relying on such indirect and generally imprecise data, it’s absolutely essential that the palaeo scientist strives to be her greatest critic. But what I’ve seen in a shockingly large slice of the Australian palaeo-science literature is not just sloppy, it’s downright disingenuous.

I’ve written recently about the things one has to take into account and attempt to correct for with dated fossil specimens, so I won’t repeat all that here. Rather, I want to draw your attention to only one specific case of monumentally bad palaeo-science published a few years ago in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA.

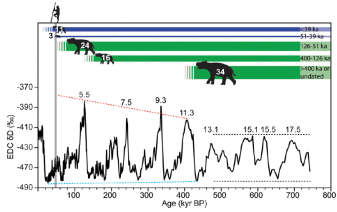

Here we see the variable time series of δ deuterium from the Antarctic EPICA ice core dataset (a proxy for temperature: more negative values indicate lower temperatures) that many have used as an indicator of changing temperatures in Australia over the last 800,000 years (as we discuss in our latest paper though, it’s not a terribly good one for Australia). Above the temperature proxy line are some fanciful extinction timelines for some megafauna species (as stated, not quality-controlled or bias-corrected, but we’ll let that slide for the moment).

The first thing you’ll notice is that there are four straight lines on the graph. The two to the right are somehow meant to inform us that the variation in the temperature proxy is constant between about 480—750 thousand years ago. While not the biggest problem by far, this is not based on any formal analysis: the top line ‘touches’ two peaks, yet it ignores the lower peaks earlier and later, whereas the bottom line touches only one trough. The real problem sets in for the two left-hand ones: the top line is drawn subjectively through the second-lowest peak and the highest peak, with the opposite done for the bottom line. All these (hand-drawn) lines are meant to make us think that the climate was relatively stable from 750—480 thousand years ago, and then suddenly got all wonky and variable after that. Hmmmm …

I think even a first-year undergraduate without any statistical training whatsoever could probably tell something was amiss with this story, but I’ll endear you with an actual statistical analysis of the data included in our paper.

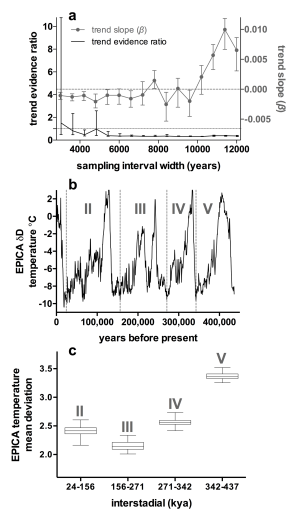

The way to get around this problem is to resample the data from a random starting point at a set interval such that the biased sampling is rendered irrelevant. Doing this a lot builds a distribution from which hypotheses can then be tested without the sampling artefact getting in the way. Focussing on the period in question (from about 450 thousand years ago) and testing for an increasing variance over various sampling interval lengths (top panel in adjacent figure), we see that there’s no evidence for a changing variance (slope) model relative to a static (null) model for intervals ranging from 3000 to > 10,000 years (after which point the interval gets too wide with which to do anything meaningful).

We also calculated a resampled ‘mean deviation’ (like a coefficient of variation, but unaffected by the changing magnitude of the standard deviation) for four periods back to the present (a single iteration is shown in the middle panel). The mean deviance (~ the variance) actual declines over most of the last 400,000 years until the modern era (24—156 thousand years) after which it increases slightly (but it is not statistically different from the previous period).

The take-home message here is that after doing the analysis properly, the exact opposite conclusion is reached. There are many, many more issues of bad science in that paper, and our review goes at least some way to addressing its main problems, and the general problems about how some bad science in Australian palaeo-ecology has hindered the progress of this field over the last few decades.

A final word. I’m certainly not denigrating the fine process of the scientific method — how we constantly update previous hypotheses with better data to modify (and sometimes completely reformulate) our theories. However, how that paper ever passed peer review, let alone appeared in a high-profile journal, is a complete mystery to me and many others. Irrespective of the conclusions reached, this sort of egregious sleight of hand should not and cannot be used to justify preconceptions, for they make a mockery of the scientific process. I hope our new paper goes some way to rectify this.

CJA Bradshaw