Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

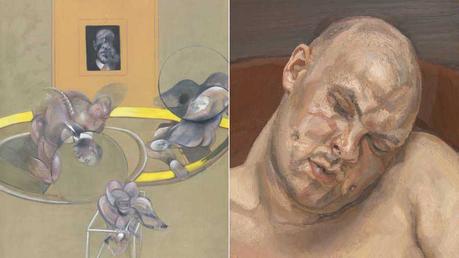

Francis Bacon Three Figures and Portrait, (1975) and Lucian Freud, Leigh Bowery (1991)

It might seem these days that even the Thames is struggling to keep to its course given the exhibition currently making waves at the Tate Britain sitting on its banks. It tells the story of British art before and after Francis Bacon (1909-1992) and Lucian Freud (1922-2011), welling up from a hot spring of works by Stanley Spencer, Chaïm Soutine, David Bomberg, Walter Sickert and Giacometti, settling in the delta of thirty or so paintings by the eponymous rivals and ending with a small retrospective of contemporary painters such as Slade graduate Paula Rego and Jenny Saville.

All too human: Bacon, Freud and a century of painting life is the title borrowed from Nietzche's book by Tate Britain for its exhibit bringing together 20th and 21st century British artists who sought a new way of capturing the physical and psychological essence of human beings through the medium of paint. After WWII, British painters made one of their greatest contributions to the art world by reinventing the European tradition of figurative painting. By 1950, Michael Andrews, Frank Auerbach, Freud, R.B. Kitaj, Leon Kosso and Bacon were banded together under the label "London School" at a time in the lives of this group of artists and friends when they all pledged allegiance to past artistic traditions and orthodoxy whilst sharing a rejection of the abstract.

But, how does one paint life? Is it possible to capture the human experience on canvas? These were the questions that concerned and fascinated the artists showcased here with Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, trapped in their world of solitude and torment, as the centrepiece.

Jenny Saville, Reverse (2002-2003)

Two Lucian Freuds?

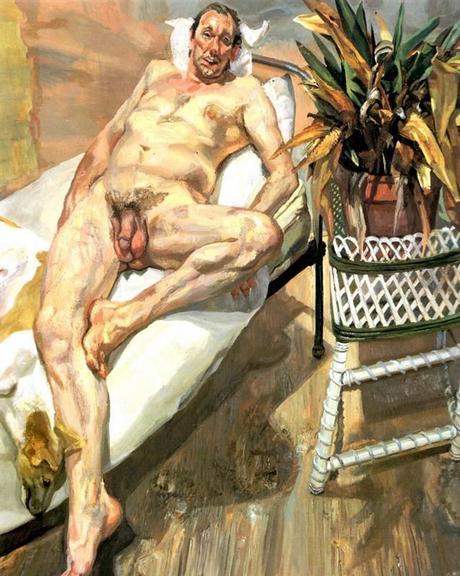

Until the 1960's, Freud appeared to be painting with a magnifying glass. In an anteroom, separate from the main gallery dedicated to his later work, is Girl with a White Dog (1950). Kitty Garman, his then wife, is depicted sitting with a dog leaning on her legs, her naked body wrapped in a yellow bathrobe left deliberately open to reveal her right breast, the left one covered and her hand cradling it as if feeling for a heartbeat. The detail with which Freud studies the various surfaces is reminiscent of the Flemish Primitives. Kitty's thick, wavy hair as compared to the dog's rough coat, from the fluffy pile of the towelling dressing gown to the tassles that braid its belt. Those were the years of Freud's fascination with Ingres so Kitty's gleaming gold wedding band could even be deemed a dedication to the French Neoclassisist.

Freud had always had an obsession with painting eyes. They seemed to him to be the source of presence and power. They could, and even moreso their movements, express everything from desire to hatred, trust to mistrust and whether they decide to look us back in the eye or not. Pupils and the enigma of their dilation on observing an object of interest or fear intrigued him. Kitty's sad eyes are like two pools full of glints and contained tears. The dog's eyes, however, are the ones that, as if a mirror in a van Eyck painting, reflect the window in Freud's studio.

Lucian Freud, Girl with a White Dog (1950)

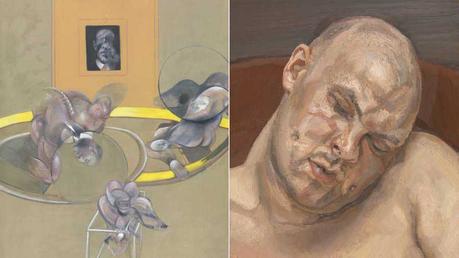

Towards the end of the 50's, Freud left drawing behind to focus on painting. He changed paintbrushes, replacing the fine, marten-hair ones with thicker, boar-bristle ones that facilitated his evolution towards those denser and more expressive brushstrokes characteristic of the later stages of his painting and displayed in the next room. There, man and beast return to center stage in the form of David and Eli (2003-2004), his assistant and his dog exposed on a narrow bed. It is a striking nude study of epic, no-holds-barred proportions. The model in all his rawness, nothing more. It's as if Freud had invented a brand new style of nude and shone a violently bright light on it, subjecting that mysterious layer that is human skin to merciless analysis. Its thickness, its flaccidity and the inherently matte colours of pale skin, inseparable from a painfully lived reality.

Lucian Freud, David and Eli (2003-2004)

Bacon and Freud: not a marriage made in heaven

In his book Man In The Blue Scarf, in which he relates his conversations with Freud while having his portrait painted, Martin Gayford recounts how, one day between poses, they were looking through a book on Van Gogh. Freud chose an Arles landscape saying: "Many people would say this is inspired by Japanese art but I would much rather this one than all Japanese landscapes of the 19th century put together. The most difficult thing is being able to draw well" and, mentioning Bacon: “Francis scribbled away constantly. His best work came solely from his own inspiration, I mean, when it wasn't based on drawing well."

Despite their differences, Bacon and Freud will be together forever in the minds of art historians. Gayford explains that the same thing happens with British artists as with the proverbial London bus delays ~ you wait for hours with no sign of one and then two arrive at the same time. In the 1880's, J.M.W. Turner and John Constable were seen as a pair and then there was nobody else until Bacon and Freud after the Second World War. Like Turner and Constable, Bacon and Freud made a bad marriage of artists, with as much dividing them as uniting them.

Francis Bacon, Study after Velázquez (1950)

Bacon, for his part, was obsessed with painting mouths: terrifying jaws at the end of eel-like necks that suck and swallow nightmares, lovers, pain, boardgames, alcohol, war and screams. It's life as a taut twine between birth, skinned flesh, violence, the great and the deep in human feeling and, ultimately, death. And, simultaneously, the most breathtaking beauty based on his innate taste for the serene monumentality of the Old Masters such as Rembrandt, Velázquez and Goya. But it was Picasso who really kickstarted his career, as did the literature of writers from Aeschylus to T.S. Eliot. This whole palimpsest comprising layer upon layer of Venetian colours, the oranges and pinks absorbed by black he daubed on the walls of his studio, transforming it into a giant 3-D palette, is what enabled him to do something that was only possible after the first Freudian generation ~ to paint trauma.

Rarely did he paint life models, prefering instead to work from photographs and movie stills. His painting came straight from his own imagination, capitalizing on every thought that entered his head "as if they were transparencies". He rejected the image as imitation. For him, it was all about that instantaneous piece of evidence transmitted directly to the brain and without the need for verbal intervention or "what happens in that instant to the nervous system". From there ,and not needing the logic of resemblance, his work would take off from his own aesthetic vision and from the beauty and energy of the strokes that, for him, represented a struggle and an intimate relationship between a painting and its painter.

Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait of Lucian Freud (1964)

Standing in front of Bacon's Study after Velázquez (1950), we are reminded of this Irish-born artist's love of the Prado Museum in Madrid. His frequent visits from 1956 onwards are described by Manuela Mena as his eyes devouring the paintings of Velázquez: “He would study the brushstrokes, which is where it's all at, right up close and with deep concentration". He would go from painting to painting, "observing his subject much like someone examining the skin of their lover." The Prado exhibited Bacon in 2009 which, in its way, forever united him with Spanish painting of the 17th century.

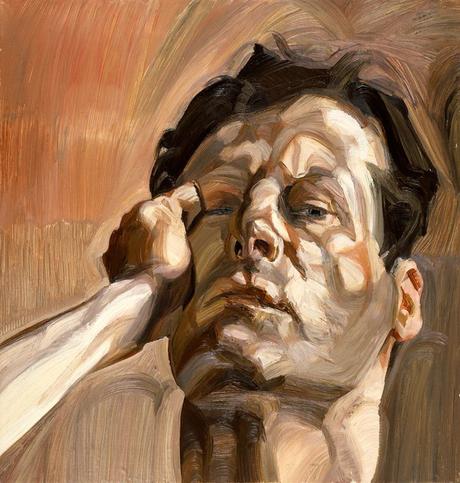

Lucian Freud, detail from Man's Head (Self Portrait 1), (1963)

Finally, the heat in this boxing ring of Tate Britain's creation rises as we approach the face-off between two canvases. In the red corner, Bacon's Study for a Portrait of Lucian Freud (1964), a painting unseen by the public since 1965, and in the blue corner, Freud's self-portrait Man's Head (1963). Freud painted Bacon twice. Bacon painted Freud over 40 times.

Francis Bacon (left) and Lucian Freud photographed by Harry Diamond, 1974

All too human: Bacon, Freud and a century of painting life

Tate Britain

Millbank, London

Curators: Elena Crippa and Laura Castagnini

Until 27 August 2018

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Bacon versus Freud, a battle history - - Alejandra de Argos -