“The Autumn Leaves of Red and Gold”

“The Autumn Leaves of Red and Gold”Whether it’s April in Paris, summer in the city, or winter in Red Square, it’s always fair weather in our house whenever we hear that lovely ballad, “Autumn Leaves.”

Composed in France around the year 1945, the music was the handiwork of a Hungarian émigré named Joseph Kosma (born József Kózma), with poetically inspired lyrics (en français, naturellement) by French author and screenwriter Jacques Prévert.

Primarily a classical and film composer, Kosma was credited with providing the scores for such cinematic classics as Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion, La Bête Humaine and The Rules of the Game, in addition to Marcel Carne’s Gates of the Night (Les Portes de la Nuit) from 1946, where “Autumn Leaves,” or “Les feuilles mortes” (“The Dead Leaves”) in its original French title, was first introduced.

And the artist who introduced the theme to audiences was the Italian-born Ivo Livi, a.k.a. French pop idol and actor Yves Montand, followed soon after by sultry singer-actress Juliette Greco. Needless to say, this gorgeous piece, with its subtle strain of gypsy love-songs and nostalgic hint of l’amour passée (a possible precursor to bossa nova, but without the delicate Brazilian rhythm), went on to became a standard with performers as one of the most romantic numbers this side of Arles.

In this country, we know it simply as “Autumn Leaves,” one of songwriter and Capitol Records co-founder Johnny Mercer’s best beloved works. His wonderful words, combined with Kosma’s sublime tune, make for a rewarding listening experience, as any romantically inclined couple can tell you:

The falling leaves drift by the window

The autumn leaves of red and gold

I see your lips, the summer’s kisses

The sunburned hands I used to hold

Since you went away the days grow long

And soon I’ll hear old winter’s song

But I miss you most of all, my darling

When autumn leaves begin to fall

American pop singer Jo Stafford is acknowledged as the first to perform and record the song using Mercer’s lyrics. In the wake, then, of its growing popularity in the States, “Autumn Leaves” entered into the repertory of a vast variety of outstanding musicians and entertainers, to include French chanteuse Edith Piaf (in both the English and French versions), pianists Roger Williams, Errol Garner and Bill Evans, crooner Bing Crosby, singer-actress Doris Day, bandleaders Stan Kenton, Artie Shaw and Paul Weston, instrumentalists Miles Davis and Stan Getz, and many others.

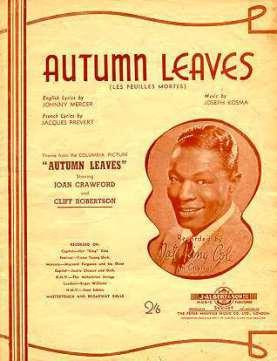

One of the best and most beautifully sung — and a viable candidate, I might add, for best all-around interpretation of “Autumn Leaves” — is the version recorded and released, in 1955, by Nat King Cole, from his Capitol album Nat King Cole Sings for Two in Love. It was also featured in the opening credits to the movie of the same name, Autumn Leaves (Columbia, 1956), starring Joan Crawford and Cliff Robertson, and directed by Robert Aldrich, with additional music by studio veteran Hans J. Salter.

Professor Luca Cerchiari, one of the editors of the anthology Eurojazzland: Jazz and European Sources, Dynamics and Contexts, in the chapter “Sacred, Country, Urban Tunes: The European Songbook,” praised Cole’s “typically immaculate diction” and his “trademark liquid, crooning vocal style.” He especially made note of Cole’s use of vowel sounds on the letters “o” and “e,” and on the consonants “d” and “t,” in the words “leaves” and “window” and “red and gold.”

Here’s a truly marvelous clip from Nat’s short-lived mid-Fifties television program, singing “Autumn Leaves” as arranged by Nelson Riddle: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=video&cd=4&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0CDAQuAIwAw&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DGnp58oepHUQ&ei=O4NCVMS-Do6eyAS38oCQCA&usg=AFQjCNGnCLO8BaJBPMD0XyonIvJukTQgMw

He paints the song in light brushstrokes, caressing the phrase, “And soon I’ll hear old winter’s song,” with a gentle, urbane assurance. In his hands, the tune takes on the theme of a fond remembrance of better times. Cole’s mellow tones, which fall on the ear like blossom honey, delivered with a relaxed and elegant air of utmost charm and sophistication mark his rendition as one of the classiest on record.

A completely different take on the number is Capitol Records label-mate Frank Sinatra’s 1957 version, as part of his thematic album, Where Are You? Masterfully arranged and conducted by Gordon Jenkins (along with Nelson Riddle on the flip side), Ole Blue Eyes takes his time with the piece, holding onto the high note of the phrase, “old wiiiiiiiinter’s song,” for as long as his lungs can manage — as if by doing so, he could hold back the inevitable sting of fate, as well as a failed love.

This is unparalleled lyricism at its boldest, a heartrending glimpse into one man’s desolation and despair. But you’ll have to go to YouTube to hear it: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=video&cd=5&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0CDUQtwIwBA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DrduLAaDQgeU&ei=n5FCVMDcJIesyASwm4HgCQ&usg=AFQjCNHp-ML6o2rm-R6lIe6dNQLMj6ZGMQ

With its darkly portentous atmosphere of gloom and doom, and complementary orchestration, Sinatra accomplishes something no other singer has been able to do: he transforms the ballad into high drama, a Shakespearean tragedy of dire dimensions — a grim game of love’s labors lost and gone, forever.

Its stark contours clash markedly with Nat King Cole’s more modest and wistful yearnings. Regret and understanding are the primary thoughts on Cole’s mind, while bitterness and betrayal occupy Sinatra’s viewpoint and underscore his joyless reading of events.

So which version is better? There is no “better” here, only different. Both artists had jazz or pop music backgrounds, and used what they learned on the stage and in the studio to excellent effect. Depending on one’s mood or mind-set, I’d say both recordings are valid, first-rate interpretations. Of course, I simply adore Nat King Cole, hands down, no matter what he sings. No other artist affects me the way he does. Lately, however, I’ve been leaning towards Sinatra. In its own context and within its sphere of influence, Ole Blue Eyes’ open-hearted depiction can speak to so many of us who’ve gone through equally wearing times.

It’s a clear-cut case of the glass being half empty or half full. If Frankie’s canister can be seen as needing a refill, then surely Nat’s bottle must be well nursed by now. And if autumn leaves eventually give way to freezing winter, which then become the blossoming spring and summer, we know for sure that good times are just around the corner.

Accentuate the positive, as the old saying goes. A saying that also happens to be a song: a song by Harold Arlen, with lyrics by none other than Johnny Mercer!

Now that’s what I call coming full circle.

Copyright © 2014 by Josmar F. Lopes