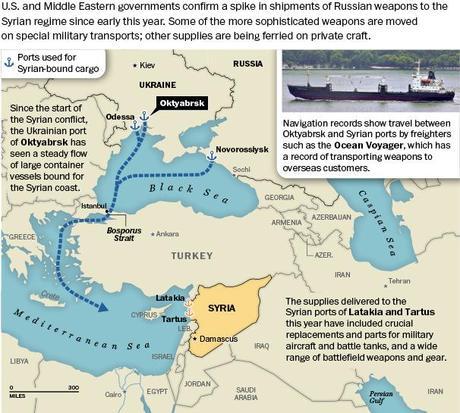

Odessa is not only Ukraine’s most important remaining port for access to the Black Sea. It has also allegedly been a key avenue for Russian companies to export, sometimes with illicit or controversial purposes, goods overseas. Russian arms to the regime of Syrian President Bashar al Assad allegedly flowed through Odessa, for example.

Odessa is not only Ukraine’s most important remaining port for access to the Black Sea. It has also allegedly been a key avenue for Russian companies to export, sometimes with illicit or controversial purposes, goods overseas. Russian arms to the regime of Syrian President Bashar al Assad allegedly flowed through Odessa, for example.

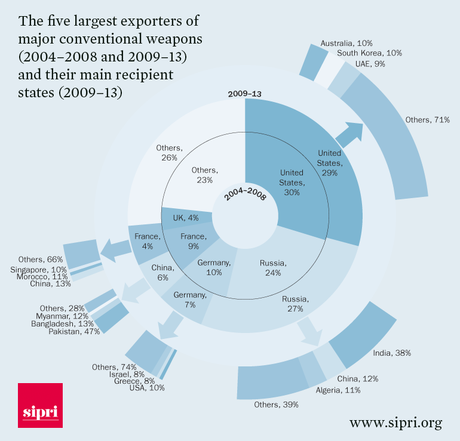

In my earlier article Arms Trade: The Crux Of The MIC I described where U.S. and Russia were supplying their weaponry as part of geopolitical game. One part of international arms trade is made via semi-official channels or through clandestine operations. One example about these activities – from U.S. side – is described in my article – U.S. Recycles Its Old Balkan Practice With Syria . Now there is also an example of implemented practice from Russian side.

Russia’s biggest, money-making exports — after oil and gas and other natural resources — is weaponry. Russia’s state-owned defence equipment export company Rosoboronexport seemingly has had a record year, reporting exports of almost $39 billion in 2013-14. The regions of Ukraine where pro-Russian separatists are rebelling is home to more than 50 factories that have been building specialized military equipment for Moscow over the last two decades.

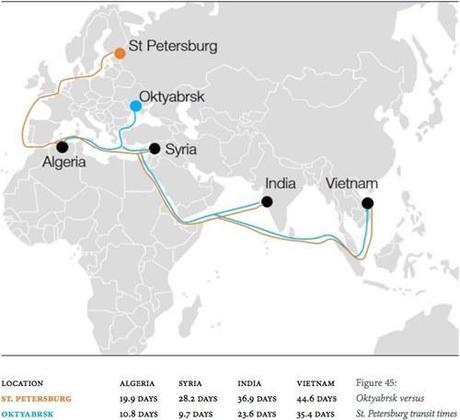

Most of Russia’s massive arms exports was channeled through the Ukrainian port of Oktyabrsk – about 100 km east of Odessa. Oktyabrsk is specially built by the Soviet Union to ship weapons and possesses a number of qualities making it well-suited for arms exports: advantageous geography, specialized equipment, transportation infrastructure to major FSU defense-industrial plants, and more.

At least until 2014 Oktyabrsk the highly secure, very Russian “specialized sea port” from which the Kremlin exported out Kh-55 cruise missiles to Iran, Pechora-2 surface-to-air missiles to Eritrea, T-72 tanks to Venezuela and South Sudan, even more tanks and rockets to Myanmar (Burma) … and all of the above to Syria.

The Odessa Network

A new study by independent conflict researchers describes a heavy volume of traffic in the past two years from Ukraine’s Oktyabrsk port, just up the Black Sea coast from Odessa, to Syria’s main ports on the Mediterranean. In late 2012, Farley Mesko and Tom Wallace – security analysts at C4ADS – began investigating an intricate network of Ukraine-based individuals and logistics companies responsible for transporting weapons out of Russia and Ukraine on behalf of government sellers. Their report – The Odessa Network: Mapping Facilitators of Russian and Ukrainian Arms Transfers (later the report) presents a picture of a very opaque system, in this case the system of maritime arms transfers related to the Russian government and former Ukrainian government. C4ADS is a ,Washington-based, nonprofit research organization whose mission is to understand global conflict and security through on-the-ground research and data-driven analysis.

Despite being in Ukraine, Oktyabrsk “is functionally controlled by Russia,” and the port is headed by a former Russian navy captain and owned by a business magnate with close ties to the Kremlin, the report said. Major Russian weapons exporters have offices there, alongside Ukrainian and Russian shipping and logistics companies the report has dubbed the “Odessa Network”. Oktyabrsk is specially built by the Soviet Union to ship weapons and possesses a number of qualities making it well-suited for arms exports: advantageous geography, specialized equipment, transportation infrastructure to major FSU defense-industrial plants, and more.

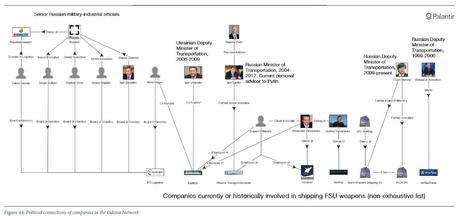

The Odessa Network is a loose collection of logistics contractors for the governments of Russia and Ukraine, not independent arms dealers. Key companies and figures in Odessa include Kaalbye Group, Phoenix Trans-Servis. Affiliated EU and Russian shipping firms such as Briese Schiffahrts (and its subsidiary BBC Chartering) and Balchart play an important specialized role in transporting particularly large or sensitive shipments. To protect their weapons shipments, some of the Ukrainian and Russian firms own or contract with multiple private maritime security companies – such as Moran Security Group, Muse Professional Group, Helicon Security, Changsuk Security Group, and Al Mina Security Group – who also operate in African conflict zones. These companies’ business model revolves around staffing ships transiting dangerous areas (particularly the Gulf of Aden and Gulf of Guinea) with heavily armed FSU (Former Soviet Union) military veterans, who provide protection from pirates. The companies work with state weapons export agencies such as Rosoboronexport and Ukrspetsexport.

The Odessa Network is not a hierarchical, unitary organization. It is better characterized as a “contacts market:” clusters of individuals and firms geographically concentrated in a particular area, and performing a specific sub-task of the weapons-export process. For example, the primary logistics contractors for Russian and Ukrainian weapons exports are shipping companies headquartered in the city of Odessa, while the financial services sometimes used to ‘clean’ profits are located in Latvia.

According report there is evidence that some of these “Odessa Network” companies employ Latvian banks known or accused of money laundering and a series of Panamanian companies run by Latvian nationals who act as “proxy directors.”is a member of the EU, and so money cleaned through Latvia can readily be transferred into safe havens in Zurich or London. Over half of the $25 billion held in Latvian banks is held by foreign depositors; the IMF estimates FSU entities account for 90% of this.

The Weapons Shipment Data in report presents dataset on Russian and Ukrainian weapons shipments, and the ships, companies, and ports used to facilitate them. The dataset includes 43 separate shipment events, and at least 21 different purchasing countries. These shipments include weapons ranging from crates of surplus ammunition to state of the art SAM systems, customers ranging from countries in good international standing to states under active international sanction, and span over a decade of time. Some of these arms transfers are well-known, while others were previously undetected. These shipments were facilitated by a comparatively small group of Ukrainian and EU companies and individuals with close ties to one another, and to senior Russian and Ukrainian governmental and military-industrial officials. The report for example notes that Kaalbye -company carried arms to President Assad’s forces in Syria in 2012 and to the Venezuela government from 2011 to 2013. Previous shipments have included cruise missiles to China and Iran, assault rifles and grenades to Angola, and tanks and RPGs to South Sudan.

Government connections

A network of Ukraine-based individuals and logistics companies—referred to as the “Odessa Network” due to its key leadership being located in Odessa, Ukraine—is responsible for transporting weapons out of Russia and Ukraine on behalf of government sellers. Odessa Network company leaders have personal and financial relationships with cabinet level officials in the Russian and Ukrainian governments.

According the report the Odessa companies’ greatest asset: connections. Link and network analysis reveals that the Odessa companies and personnel are the center of a rich network of businesses and individuals who provide all the services necessary for a weapons shipment to occur. The Odessa Network firms are logistics contractors for the Russian and Ukrainian governments. State agencies such as Rosoboronexport and Ukrspetsexport own the weapons and broker almost all foreign sales. The Odessa Network companies play a critical role in making these arms transfers happen, but they only do so on behalf of powerful customers in Moscow and Kiev. The key assumption is that there must be persistent links and contractual relationships between the Odessa Network and government officials. The Odessa Network has moved billions of dollars of advanced military hardware, which indicates a high level of government trust in its competency and honesty, implying contact between leaders on both sides.

Photo credit C4ADS – http://www.c4ads.org/

Click HERE for bigger picture.

Wider view

The maritime shipments by Odessa Network are only one part of Russia’s and Ukraine’s arms trade. The Norwegian firm Eide Marine Services is the second most frequent weapons transporter in our dataset (after Kaalbye). Eide is a perfect example of how EU firms provide specialized ships to handle large or unusual cargo the Odessa firms cannot, such as warships and submarines. Eide is one of the few firms which possesses exactly such a ship, the Eide Transporter, which has been used multiple times to move unusual Russian military cargo to foreign customers. This includes Tarantul-class missile corvettes, Gepard-class frigates, and Svetlyak-class patrol boats to Vietnam, and Kilo-class submarines to China. However Eide-Odessa connections are unclear.

Many of Russia and Ukraine’s customers are geographic neighbors or landlocked, making it impractical or impossible to use sea transportation. For example, when Russia exports weapons to neighboring Kazakhstan it does so by plane, rail, or truck. Similarly, even distant customers may be purchasing military equipment that is typically not moved by sea. For example, Russia has a $300 million contract to supply Su–30 MK2 and Su–27 SKM fighters to Indonesia, but these are transported on An–124 transport aircraft, not ships. Similarly, Ukraine has a contract to supply BTR–3E1 APCs to Thailand, but previous shipments have been flown on an Il–76 to U-Tapao Airport, not shipped.

Selling of advanced weapons also indicates the facilitator of weapons shipments are an important foreign policy tool. Governmental ownership of exported weapons since the early 2000s confirms a narrative of Russian politics that emphasizes reassertion of state control over national assets (defense plants, oil and gas, industrial concerns, etc.) and profits resulting from sale of these assets being distributed to regime stakeholders via sanctioned corruption in exchange for political loyalty.

Exceptionalism

The situation in Ukraine has its effect to arms trade – not only to Russian exports but to imports too.The volume of import substitution program in the defense sector is 22.8 billion rubles, “Kommersant” writes citing a senior source in the Russian defense industry. “The sanctions will encourage the expansion of the programme of import substitution and speed up the development and introduction of new domestic technologies.”

Downriver from Dnepropetrovk is Zaporizhia, home of Motor Sich. While Russia was annexing the Crimea from Ukraine the Motor Sich inherited most of the former Soviet Union’s aeronautical engine manufacturing capability Motor Sich signed a new, upgraded co-operation agreement with Rostec, the umbrella organization for Russia’s defence industry.

Speaking about sanctions it is a bit ironic that the embargo on the rotorcraft engine exports to Russia will not have a negative impact on one significant contract – the delivery of 63 Mi-17V-5 tactical transport helicopters for the Afghan armed forces ordered by the US for some $1.33 billion.