(Previous Entry: The Opposite of Fear)

(Previous Entry: The Opposite of Fear)We Latter-day Saints have become so accustomed these days to having false doctrine preached at us in church that we barely even blink anymore when we hear it.

Last week in my local sacrament meeting, both speakers gave talks on the same topic, the law of tithing, and both promoted views that were not only not found in God's word, but were actually outright perversions of the law.

It would be unfair to blame the speakers for the misinformation they were spreading. After all, they were only repeating the same myths and assumptions most of us have been taught since childhood, and the teachers and parents who taught them to us did not know any better, either. Some of these false teachings are that tithing is the Lord's money; that a tithe constitutes ten percent of our total earnings; that we must always make sure to pay tithing first before paying our bills; that tithing money goes to help the poor and needy; that by paying a full tithe God promises to bless us individually; that tithe paying is a commandment that every member of the church is expected to obey regardless of circumstances; and that tithing must be paid before anything else even if it means your children will go hungry.

None of those assumptions can be backed up by scripture, but that latter assumption, perhaps the most insidious and widespread perversion of God's law currently being promoted from the pulpit, is typified by the following statement which appears in the current issue of The Ensign magazine:

"If paying tithing means that you can’t pay for water or electricity, pay tithing. If paying tithing means that you can’t pay your rent, pay tithing. Even if paying tithing means that you don’t have enough money to feed your family, pay tithing." (Aaron L. West, Sacred Transformations, December 2012)If we are going to correctly observe God's law of tithing -and make no mistake, it is most certainly a law- perhaps it's time we clear our minds of the detritus that has accumulated from decades of secondhand information, and get the straight skinny directly from the Lord himself. After all, how can we say we understand a law if we haven't even read it?

First, some background: On December 7, 1836, Bishop Edward Partridge and his counselors officially defined tithing as 2 percent of the net worth of each member of the church, after deducting debts. This money was put to covering the operating expenses of the Church, and it appears to have been adequate for a time. Still, this was man's law, not God's. Apparently no one in the young Church had thought to ask God about it yet, so He had not weighed in on the matter.

Two years later, when the Church was eight years old, some 15,000 converts had already emigrated from their homes and gathered to Missouri, the new Zion. Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon, who constituted the First Presidency at the time, were spending all their time dealing with and settling this huge flow of immigrants, to the exclusion of being able to provide a living for their own families. Things were at a point where Joseph and Sidney must either be compensated for their time, or they were both going to have to stop what they were doing and go out and get a real job. On May 12th the two men took the matter before the High Council of the Church. George W. Robinson recorded the minutes:

The High Council voted eleven to one (George Hinkle vigorously opposed "a salaried ministry") to further contract the two men for their services, being careful to note that the money was "not for preaching or for receiving the word of God by revelation, neither for instructing the Saints in righteousness," but for work in the "printing establishment, in translating the ancient records, &c, &c." (ibid.)The Presidency laid before the High Council their situation as to maintaining their families in the situation and relation they stood to the Church, spending as they have for eight years their time, talents, and property in the service of the Church and now reduced as it were to absolute beggary and still were detained in the service of the Church. It now [had] become necessary that something should be done for their support, either by the Church or else they must do it themselves of their own labors. If the Church said, "Help yourselves," they would thank them and immediately do so, but if the Church said, "Serve us," then some provisions must be made for them. (Scott Faulring, An American Prophet's Record, Pg 182.)

Richard S. Van Wagoner, in his biography of Sidney Rigdon, further explains:

What the High Council did instead was offer the men 80 acres for their families to live on. So now Joseph and Sidney had some ground under them, but no walking around money. Maybe if they had asked for a more reasonable salary to begin with, there might not have been such an outcry. (Frankly, I blame Rigdon for the overreach. That just sounds like Sidney Rigdon to me.)After negotiations, they agreed to offer Rigdon and Smith an annual contract of $1,100 apiece, more than three times what the average worker of the day could earn. Ebenezer Robinson, the High Council's clerk, later wrote that "when it was noised abroad that the Council had taken such a step, the members of the Church, almost to a man, lifted their voices against it. The expression of disapprobation was so strong and emphatic that at the next meeting of the High Council, the resolution voting them a salary was rescinded." (Richard S. Van Wagoner, Sidney Rigdon, Pg 230.)

Anyway, the Church had been growing faster than anyone had anticipated, so it was past time to get the Lord's opinion on how to handle the financial end of things. Even though Bishop Partridge had declared tithing to be 2 percent of net, Partridge was not authorized to set doctrine; only God could do that. So in July of 1838, Joseph put the question to the Lord as to how all this was intended to work, and the answer is what we now know as the law of tithing. This law consists of the entire chapter of D&C 119, and takes up all of seven short verses. You can read the whole thing inside of half a minute. Why don't you grab your scriptures and do that right now? Or just click here to see it online. Then let's analyze it together.

The first thing you may notice about the law of tithing is that it concisely addresses two important questions:

1. How much are members expected to contribute?

2. What are those contributions to be spent on?

Those who have been conditioned by a lifetime of false propaganda about tithing may have difficulty coming to the realization that a "full tithe" constitutes less than you probably thought it did. A lot less. There may be some things in life that are difficult to bear, or that constitute a sacrifice, but tithing,when properly understood, should not be one of them. The Lord designed it to be easy, painless, and cheap.

But let's get to that later. Before we look at how much we are expected to pay in tithing, let's jump to number 2 and look at what tithing funds are intended to be spent on. Broken down, they are really quite simple:

1. The building of the Lord's house.

2. The laying of the foundation of Zion and for the priesthood.

3. The debts of the Presidency of the Church.

You'll notice there's nothing in there about helping the poor, earthquake relief, or any humanitarian aid. Charitable giving is something we are definitely commanded to do, but believe it or not, charitable giving is something that is separate from tithing. The purpose of tithing, in a nutshell, is to pay for the costs of managing Church affairs. Every faithful member is expected to shoulder his share of those costs. If done correctly, paying tithing is painless, and should leave plenty left over for charity. If done according to the dictates of man, it can be quite difficult, and charity often gets left behind.

You'll also notice when reading the law of tithing that it contains no mention of any blessings accruing to those who comply with the law, although verse 6 does contain something that looks a bit like a curse upon those who fail to observe it.

And here's something you might find curious. For all this talk we keep hearing about tithing being a commandment, no form of that word appears anywhere in this section. Why do you suppose that is? The attentive reader will also notice that the words "obey" and "obedience" don't appear within the law of tithing, either. Everywhere else in scripture where we are given a commandment, it's pretty clear that what we are being given is a commandment, isn't it? So why not here?

Could it be that The law of Tithing is not what the Lord would normally consider a commandment? Oh, it's very clearly an obligation, make no mistake about that. We are told that if we fail to observe the law of tithing (in this instance, at least, the Lord uses words such as "observe" and "keep" in lieu of obey), we won't have a Zion society. So what is the law of tithing if it isn't a commandment?

Well, it's a law.

Confused yet? That's probably because most of us have come to attribute 21st century meanings to 19th century words, and when we think of laws we often think of them the way we do man-made decrees; statutes we are ordered to obey. The meaning of this other kind of law -the law God introduces- is often related to cause and effect.

Now of course there is often some overlap when discussing laws and commandments, but they are not precisely synonymous. Commandments often operate on some direct spiritual motivation; that is, they need no set of instructions to be complied with. Their execution is self evident.

When Jesus said, "if you love me, keep my commandments," we understand His meaning right away. We love him, therefore we desire to follow his wishes. Implicit also in that statement is that those who don't love Jesus probably won't obey his commandments. They wouldn't be motivated to. Either way, they are called co-mandments, not demand-ments. A tyrant may demand something of you, but God asks his disciples to "come" with him, which is the reason for the suffix "co-" which implies we come willingly, we are co-operating with his will, rather than as unwilling subjects of a tyrant who forces compliance to his demands. To the person who is truly born again in Christ, the desire to keep the commandments is inherent in the conversion. Following the will of Christ is something you find you want to do, and which therefore comes easily. As a rule, you usually don't have to have a commandment explained to you.

For example, when Jesus said, "a new commandment I give unto you, that you love one another," his followers did not then require any detailed set of instructions about how love operates. Once you experience the unconditional love of the spirit, you don't need to be told how to be compassionate or charitable; you are motivated to act by the pure love of Christ.

Once the Holy Ghost has filled your heart with mercy (the scriptures say it's your bowels that are filled, but I'm going to go with heart), then as you come across someone who is hungry, you'll feed him, if you see someone thirsty, you'll give him drink, if you see someone naked, you'll clothe him, and so on. You are motivated on a spiritual plane to act. You don't need a list of rules explaining how mercy works.

On the other hand, the use of the word "law" in section 119 has little to do with a command to pay our tithes. It is not about obeying a law. Section 119 is concerned with explaining how and in what manner the tithes are to be obtained, and to what purposes they are to be spent. In that sense, the law is procedural, by dictionary definition it is "a rule of direction."

Before God revealed His law of tithing, members of the church were quite willing to tithe, they just didn't know how, they didn't understand the proper procedure. Section 119 spelled it out for them. It provided the rule of direction as to how it was to be accomplished, both as to receiving and disbursing. That is what is meant by the law of tithing: it refers to procedural law, the process of obtaining and disbursing the tithes. It has almost nothing to do with obedience.

This is not to say that the law of tithing need not be observed. The Lord is very clear that it is to be strictly kept, at least by those who wish to remain worthy to abide in Zion. But human nature being what it is, actually keeping the law as it was given has constantly been a challenge;and not so much for the members as for the leaders of the Church who have constantly been caught tampering with it.

There are a few places in the D&C where tithing is briefly mentioned (64:23, 97:11-12, and 85:3), but if you're looking for the actual Law of Tithing, you will only find that in section 119. That is the Law of Tithing in its totality. We know so because in verses 3 and 4 the Lord tells us this will be the beginning of the tithing of His people, and that it will be "a standing law" unto us forever. So whatever you believe about tithing, if it's not in there, it's not part of the law.

Painless Payments

In the first verse, the Lord announces the first part of the tithe. It is for all the surplus property to be put into the hands of the bishop. That would have been a surprisingly easy term to comply with, as the early Saints understood the meaning of the word "surplus" to be any property they had which they didn't really need or have use for. If Brother Zeke was raising chickens, he got to keep all the chickens his family could eat for the year, plus enough to barter for other necessities, along with as many eggs as his family could consume or trade or sell for other necessities. If he had extra hens and eggs beyond his family's needs, that was Zeke's surplus, and those went to the bishop for his tithe. These were chickens Zeke would barely miss, and the Lord made it that easy to part with his property on purpose. Tithing is not a test. It is meant to be practical, to accomplish a purpose. Paying it was not intended to be hard for anyone.

There was nothing new and unusual about this method of tithing. Joseph Smith clarified certain aspects of the law, as it has often been misunderstood. For instance, in Genesis 14 of the King James Version, we are left with the impression that Abram paid one tenth of all his possessions. That would have been a lot for Melchizedek to carry back, because Abram had a lot of posessions.

Yet in Joseph Smith's newer translation, we find that "Abram paid unto him tithes of all that he had, of all the riches which he possessed, which God had given him more than that which he had need. (JST Genesis 14:39) Still a lot, but now we see it's not a tenth of everything. Abram gave only a tenth of his surplus. God has never required his people to "pay him first," or to give to the Church before meeting the needs of our families. God's law has always been extremely fair. But men always seem eager to tweak God's law to their advantage.

Joseph Smith had not even been in his grave a month before the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles issued an edict declaring that instead of giving of their surplus, the Saints were to henceforth give "a tenth of all their property and money...and then let them continue to pay a tenth of their income from that time forth." There was no exemption for those who had already given all their surplus. The new rule was a tenth of everything right off the top.

And note that the twelve didn't pretend this change represented a revelation from God; they just needed more money, and issued a decree to get it. They arbitrarily changed the definition of tithing just because they wanted to. Apparently some people don't understand the meaning of "a standing law forever." Oh well. The Prophet was dead. New Management, New Rules.

And guess what? Two weeks after that announcement, the Twelve voted to exempt themselves from any obligation to pay tithing at all, not even a tiny bit on their surplus. God's "standing law forever" had only been in place for six years, and already it was being eroded by those charged with administering it.

It shouldn't come as much of a surprise to learn that the number of members who bothered to pay any tithing at all soon fell dramatically. Over the next few years all manner of punishments were tried and proposed against delinquent tithe payers, from fines to excommunications. Official and semi-official decrees as to what and how much constituted a full tithe were constantly in flux, and always skewed to favor Church leaders over the rank and file

By the time the Saints had settled in Utah, all talk of surplus had vanished from the dialogue. New converts were expected to turn over ten percent of all their property at the time of their baptism, then another ten percent upon arriving in Utah, and ten percent more every year thereafter. General authorities had either misread the Lord's words in Section 119, or were simply lying outright when they taught that tithing was "one tenth of all we possess at the start, and then ever after one tenth..." (Journal of Discourses 15:308, 15:359, and 16:157). The result of this anarchy was that it wasn't long before less actual tithing was being collected per capita. According to historian Michael Quinn:

Otherwise faithful Mormons withered before an overwhelming tithing obligation. Young told the October 1875 general conference that neither he nor anyone else "had ever paid their tithing as it was revealed and understood by him in the Doctrine and Covenants."You can say that again. You have to wonder how much better compliance would be if the leaders simply showed the members that true tithing doesn't have to be a sacrifice; it's supposed to be simple and easy.

If we are to fully understand the law of tithing as given by the Lord, we are going to have to shed our modern notions about the meanings of words such as "surplus," "interest," and "income" and instead examine the meaning of those words as understood by most Mormons at the time the revelation on tithing was given. As it happens, Noah Webster published the first dictionary of the American language in 1828, and the meaning of the words as commonly understood by the Saints in that day can be found by looking up those definitions.

Plus, Plus Plus, Equals Over-Plus

Webster defines "surplus" as "that which remains when use is satisfied; excess beyond what is prescribed or wanted."

In the largely agrarian society of the early Saints, that might be additional chickens, cattle, apples, or anything over and above what a person might require for his family's needs. The early Saints would have been surprised at the modern assumption that tithing should be paid before you pay anything else, because in order to pay from your surplus, you have to wait and see what you have left over. That's why tithing was paid annually. In the Missouri-Nauvoo period, you would have to get your bills taken care of first, otherwise you would have no idea what your surplus was going to be. Surplus is that which is left over after all other expenses have been deducted.

The word Surplus is also defined in Webster's 1828 as being synonymous with the word "overplus," a word seldom used anymore but which happened to be the term to describe tithing used by John Corrill, one of the scribes who had been enlisted by Joseph Smith to write an early history of the Church. (Corrill's fascinating book, A Brief History of the Church of Christ of Latter Day Saints, published in 1839, has been hard to come by until quite recently. You can now find it reprinted in its entirety in The Joseph Smith Papers, Volume 2-The Histories). Here is how Corrill explained tithing among the early Saints:

The word Surplus is also defined in Webster's 1828 as being synonymous with the word "overplus," a word seldom used anymore but which happened to be the term to describe tithing used by John Corrill, one of the scribes who had been enlisted by Joseph Smith to write an early history of the Church. (Corrill's fascinating book, A Brief History of the Church of Christ of Latter Day Saints, published in 1839, has been hard to come by until quite recently. You can now find it reprinted in its entirety in The Joseph Smith Papers, Volume 2-The Histories). Here is how Corrill explained tithing among the early Saints:If a man gives for the benefit of the Church, it is considered a voluntary offering. Yet the law requires or enjoins a consecration of the overplus, after reserving for himself and family to carry on his business.(Emphasis mine.)Common sense would tell us that the suffixes "plus" in the words surplus and overplus would mean something like "in addition to," or "above and beyond," but you would be surprised how many Mormons will look at verse one in section 119 and remain convinced it means the early Saints were to give up everything they owned. Never underestimate the effectiveness of the indoctrination you received in Primary.

We see in verse four of God's law of tithing that after giving this initial surplus, "those who have thus been tithed shall pay one tenth of all their interest annually." Well, that's an unusual word in that context, at least by modern standards. Not sure about the meaning of the term "interest" to the early Latter-day Saints? The pertinent definitions provided by Webster's 1828 inform us that it is a "share; portion; part; any surplus advantage." There's that word surplus again. It turns out that Interest is practically synonymous with surplus. As is also the meaning of increase.

Not sure what is meant by "surplus advantage"? For the definition of advantage we find "Benefit; gain; profit" also "Interest; increase;" and look, there's overplus again. But wait. Back up. Doesn't "gain" mean the same as earnings or wages? So in modern times when we are paid wages we have gain, right? Aren't we then supposed to tithe ten percent of our wages, since our wages represent a gain?

Nope. Not so fast. the meaning of Gain as it pertains to a person has always been akin to what profit would be to a business. The money coming in to a business might consist entirely of what it gets for selling its products, or sales revenue. But all that revenue does not give an accurate picture of how much money the business has actually gained, because a lot of that money has to go back out to cover expenses. What is left over after expenses constitutes how much money the business actually ends up with. That is the profit. Only when the business sees the profit left over has it experienced gain.

Similarly, your wages or earnings have always been defined as compensation for your time and labor. It is an even trade of value for value. It is not gain. There is no "gain" accrued when you receive your wages. You are simply being evenly compensated, which means given even value. Everything is still in equal balance when you got paid. You made an even exchange of your time in exchange for their money. There is no gain or overage involved in that transaction. There is no gain because there is no increase involved. Only after you have met your expenses can you enjoy your gain which is the money you get to use as you wish, to buy what you want, to save for some future purchase, or even to fritter away.

Still with me? Gain, Increase, and Interest are all synonymous with what you have left of your wages after providing for your needs. After you have provided for your needs, you get to use the rest of your money to satisfy your wants. (By the way, being able to tell the difference between what you need, and what you merely desire, is the mark of a mature adult. If you can honestly differentiate between the two, congratulations, you're all grown up.)

Today we might call this surplus our "discretionary income," the money we have left over after our fixed costs have been met and our basic living expenses covered. That's why complying with God's law is easy. Tithing isn't ten percent of everything you have. It's more like ten percent of ten percent. Who can't contribute ten percent of their discretionary income to help pay the costs of running a Church?

Well, actually, some people can't. They would be those who have no discretionary income, no surplus whatsoever; for whom everything they take in is immediately required just to survive. Unlike the way many believe today, the Lord never intended for the sick, the crippled, and the widowed to give what they did not have. Section 119 verse 3 tells us "and after that, those who have thus been tithed" (i.e. those who had a surplus to begin with) "shall pay one tenth of all their interest annually." That isn't everybody.

Only those who had already possessed tithe-able surplus were expected to continue to tithe ten percent of their additional surplus at the end of each subsequent year. The truly destitute have no surplus, so they are not expected to tithe. God is not a monster. Your Sunday School teacher may insist that tithing be paid before the rent and food, but the scriptures don't teach that. The scriptures teach "if any provide not for his own, and specially for those of his own house, he hath denied the faith, and is worse than an infidel."

Do you see how simple the Lord made it for us to provide for the administrative costs of the Church? When the institutional Church is operating properly and within its defined boundaries, it shouldn't require a massive sacrifice from the members. The law of tithing, as given to us by the Lord, is a simple law; it is only when we turn it into something difficult and complicated that we begin to see it as a sacrifice and a duty.

And there's the rub. Keeping the Church operating within the bounds outlined within the law has always been the challenge, hasn't it? That's why it's up to the members to hold the leader's feet to the fire so they don't succumb to their own human natures. Remember, it was the members who vetoed the plan to allow Joseph and Sidney to take home three times the the wage of the average worker of that day. If the members had taken the attitude we do today, "Well, they are the leaders, and we have no right to question them," then an injustice would have occurred, and the sacred tithes of the members would have been misappropriated.

Joseph Smith had to abide by the veto of the members who contributed the funds even though he was the guy who started the whole dang church in the first place! Everyone understood he was in charge, didn't they? Yet even The Prophet Joseph Smith could not do whatever he wanted. He had to ask, and then he was at risk of being told no.

D&C 119 informs us that the law of tithing is specifically intended to pay the debts of the First Presidency, so we should see that is accomplished. But how are those debts defined? It has been an open secret that the general authorities of the Church receive a very comfortable salary, although it is often described as a "stipend" or "modest living allowance." As the ones who are covering the costs of these allowances, the tithe payers should be aware of how much money that actually comes to. But that information is hidden from us by the very men who receive those salaries, in direct violation of the Lord's word on the subject.

(One of the many things I liked about presidential candidate Ron Paul is that he understood the meaning of "servant." When he announced his candidacy he declared that if elected, he would accept a yearly salary of only $39,500 because that represented the median salary of the average American. I have no idea what the median yearly salary of the average Latter-day Saint is, but I'd venture to guess it's even less than that. I also don't know how much money our servant Thomas Monson is given to live on, because he won't tell us, but don't you think it shouldn't be much more than the average yearly earnings of the people who provide that salary? I do. What do you want to bet Monson's "modest allowance" is closer to the salary of the President of the United States than it is to your own?)

Almost from the beginning in the Church, general authorities were loaning themselves large amounts of money out of the tithing fund for their private use. As reported by historian Thomas Alexander, "By March 1899 outstanding loans totaled $115,000, much of which, one authority said, would never be repaid 'in this life'..." (Mormonism In Transition, Pg 100.) Stake Presidents were granted $300-$500 salaries cryptically labeled "travel costs" from tithing funds that poorer Mormons were struggling to provide them with.

But what about those promised blessings? Doesn't the Lord through Malachi promise to open the windows of heaven and pour out a blessing upon all the faithful Latter-day Saints who unquestioningly pay their tithes on time?

Well no. Malachi wasn't talking to the tithe payers. He was talking to the priests who had been collecting money for the poor and were keeping most of it for themselves.

It is a testament to our willingness for self-indoctrination that so many Latter-day Saints constantly quote the verse in Chapter 3 that asks "will a man rob God?" and assume the Lord is rebuking the people for withholding payment. When you read the previous chapters and verses you will see that Malachi, as God's mouthpiece, is accusing the Church leaders of embezzling. The tithes had already been paid by the people; they were simply being held up by the leadership. To paraphrase the famous words of King Solomon, "So what else is new?" (Ecclesiastes 1:9)

It can be confusing to some people why God would be angry at the priests for keeping the tithes to themselves, since the people's tithes were the very thing the Levite Priests were granted for their livelihood. It was the job of the Priest to run the temple, and tithes contributed by the people were the way in which the priests were to be compensated. It was all on the up and up. It therefore makes little sense to some people to see the priests accused of keeping the tithes for themselves when paying the priests was the very purpose of the tithes in the first place.

But the key words here are "tithes and offerings." As it turns out, there were two tithes that went to compensate the priests: first, everything that grew out of the earth was tithed for their support. There was also a second tithe, known as the cattle tithe, that was to be shared between the priests and the offerer. It's likely that the priests were taking more than their share of the meat from these offerings, and selling some of that meat for personal gain. And there was yet a third tithe, the annual tithe levied for the relief of the poor, and it was the theft of that tithe that seems to have gotten God and Malachi to come unglued. "Will a man rob God? Well You have robbed me, even this whole nation!"

In other words, the priest class had not only been robbing God, they had been stealing the offerings of the people -the whole nation- and keeping some or all of it for themselves. Why did the priests find it necessary to embezzle? Silly question, for if we extrapolate forward 400 years to the time of Christ, it's obvious the priest class was by then completely corrupt. But to give the priests in Malachi's day some benefit of the doubt, scholars suggest it was normal human nature for these men to be worried they might some day have to do without if they failed to keep extra stores in reserve. Others, pointing to Matthew 23 and Luke 11, suggest the priests had simply lost the sense of proportion with regard to what was important in religious observance.

Nevertheless, God used Malachi as his spokesman to promise these wayward priests that if they would stop hoarding the offerings and bring all those tithes into the storehouse to be properly distributed among the needy, He, God, would open the windows of heaven and pour out a blessing upon the priests; blessings so abundant they might never have to fear shortages again. Try it my way, says the Lord, and see if things don't start to work out better.

The Problem With Overpaying

One of the unintended consequences of giving too much of our substance to the Church, is that afterwards we often have little left over to give to the Lord.

But hold on. Haven't we always been taught that this is the Lord's money and that when we tithe to the Church we are in fact giving it to the Lord?

We may have been taught that by someone, but we weren't taught it by God. Nowhere in the Law of Tithing is there any suggestion that by building a temple, or laying the foundations of Zion, or paying the debts of the First Presidency, we are giving that money back to the Lord. We were given the law of tithing because Joseph Smith asked God how it was to be done and the Lord told him. The law does not refer to the money or property as belonging to God. It is earmarked to pay the expenses of the Church.

If you want to give directly to the Lord, the scriptures tell us in several places how best to go about doing that:

"I was hungry and you gave me meat; I was thirsty, and you gave me drink; I was a stranger, and you took me in; naked, and you clothed me; I was sick, and you visited me; I was in prison and you came unto me. Inasmuch as you have done it unto the least of these my brethren, you have done it unto me." (Matthew 25:35,36, 40)

"When you are in the service of your fellow beings you are only in the service of your God." (Mosiah 2:17)Paying a tithe in support of the Church has its place. But is it any more important than giving an offering to the Lord? There is only one way to give directly to the Lord, and that is by demonstrating compassion for our less fortunate brothers and sisters.

The tragedy in all this is that by overpaying tithing most of our lives, we Mormons have talked ourselves into believing that our duty has been fulfilled. And yet our tithes to the corporate Church do next to nothing in assisting the poor and needy among us. A simple reading of the law in section 119 shows us that the care of the poor and the needy was never the purpose of tithing in the first place. In addition to the small donation the Lord requires us to tithe for the support of Church management, we are still required to provide a generous offering to the poor, but how often are we admonished from the pulpit about remembering our fast offerings?

I'm afraid that in the minds of most members of the Church, the fast offering is an afterthought, something less important than "paying a full tithe." We are taught from our youth the lies about the payment of tithing being like purchasing fire insurance to keep us out of the fiery furnaces of hell, and we believe it without question, along with stories of how the Lord will bless us when we pay our tithing, or how sacrificing to give money to the Church is the way we demonstrate our devotion to God.

Yet the scriptures teach us that to the extent such blessings accrue, they arrive as a reward for helping those in need, not by paying tithes to Salt Lake. We have come to see things exactly backwards. We give much more than is required to the Priests of Levi, But when approached on the street by someone who is truly in need, we clutch our money tight to our bosoms.

Yet the scriptures teach us that to the extent such blessings accrue, they arrive as a reward for helping those in need, not by paying tithes to Salt Lake. We have come to see things exactly backwards. We give much more than is required to the Priests of Levi, But when approached on the street by someone who is truly in need, we clutch our money tight to our bosoms. We tend to focus much, much more on our obligation to the Corporate Church than we do to our neighbors, even those living within our own wards. If the Lord himself were to speak at your next sacrament meeting, where do you think he would suggest the bulk of your discretionary spending be sent? Where do you feel it is most needed?

There may have been a time when the Church truly needed additional tithes to meet its expenses, but that day is far behind us now. It seems to me that today the "church" side -the community of believers made up of individuals- is in much greater need of assistance than the corporate side. In times like these when so many of our brothers and sisters are experiencing increasing hardship, don't you think God would want us to be focusing as much attention on the needs of our neighbors as we do on the debts of the Presidency?

Why don't we hear the bishop announcing the opportunity to take part in a Fast Offering settlement at the end of the year? For that matter, why do we even still hold tithing settlement? Tithing settlement is an anachronism that has outlived its purpose, unless that purpose is intended as an opportunity to interrogate the members and instill unnecessary guilt and fear. What other reason is there to attend one of these meetings? Even those who believe they are required to contribute the full 10 percent of their earnings usually have already taken care of that on a monthly basis. So why an annual tithing "settlement" come December?

Settle Down There, Hombre

The original purpose for a tithing settlement can be found in that word "settlement." In the old days, many of those who could pay their tithing either monthly or quarterly in cash did so. But let's say Brother Zeke the chicken farmer had a bountiful year. His hens hatched hundreds of baby chicks, and his cows gave birth to 10 calves. Some of those chicks grew to adulthood and were eaten at the dinner table, others were sold so that Zeke could provide other necessities for his family ("man shall not live by chicken alone"). When the end of the year rolled around, Zeke found himself with a surplus of let's say 60 laying hens over and above what his family needed to thrive, and an increase of ten cows over what he started with in January.

So Zeke would contact the bishop and arrange a time to give the bishop six of those surplus hens, and one of the calves. In this way Zeke would "settle" his tithing with the bishop, as would any other farmer who had tithing "in kind" (which means payment in something other than money). It would then be the job of the bishop to find a buyer and convert that livestock into cash to be forwarded to Salt Lake. In those days bishops were allowed to keep ten percent of all the money they collected before sending the rest to Church headquarters. It was only fair, as finding buyers and sellers for crops and livestock could be a time-consuming endeavor.

That's how tithing was "settled" back in the day. But since most of us now deal in cash or check, we have no need to have the bishop settle our affairs for us in that manner. But tithing settlement is still held every December anyway, so go ahead and show up if you want to. Just don't expect the bishop to thank you for bringing any chickens with you, unless they're already cooked and in a bucket with a side of cole slaw.

How To Figure Your Tithing

Some folks, like farmers and ranchers, have either an increase or a decrease in their fortunes each year. If a Utah cattleman owns a thousand cows, and in a given year those cows give birth to a thousand calves, it's easy for the rancher to figure his tithing. He now possesses 2,000 head of cattle, but he does not pay tithing on all 2,000. Only half of those cows in his possession represent his increase or his annual interest, so out of that thousand he sells 100 cows and turns the money over to the bishop.

Easy and painless. He still has 900 more cows than he started out the year with, and he was able to fulfill his obligation to the Church. He can sell some or all of those extra head to support his family, expand his operations, and even donate some beef or cash to the poor. If he's lucky, next year these additional cows will bear more calves, further increasing his own fortune along with the coffers of the Church. If enough Latter-day Saints were to contribute the tiny percentage the Lord actually requires, the Church would have plenty to fund its operations, and the poor among us would be well taken care of because we wouldn't be siphoning so much of our substance off to Church headquarters.

But what about the average guy or gal who labors for a fixed wage? How do you figure your "increase" if your earnings remain pretty much the same? In 1970 the First Presidency issued a statement intended to clarify all that. (Guess what? It didn't.)

"The simplest statement we know of is the statement of the Lord himself, namely, that the members of the Church should pay 'one-tenth of all their interest annually,' which is understood to mean income. No one is justified in making any other statement than this."Now, why do you suppose the First Presidency quoted the Lord's use of the word "interest", and then added the comment "which is understood to mean income" right after it? Understood to mean income by who? I'll tell you who. The people in Joseph Smith's day. That's who.

But they understood the meaning much differently than you probably do.

If you were raised in the government schools like the last three or four generations of Americans, you probably grew up thinking income means "everything that comes in." Well, that's what you may think it means, but that is not the meaning of the word either historically, traditionally, or by legal definition. Income is more properly synonymous with profit. In other words, your income is the money you have for your personal use after your expenses have been deducted, not before. Your income is not your gross earnings or your wages, and it is not your take home pay. The early Latter-day Saints all understood income to be one's net share or "interest" after deducting the basic expenses required for living.

You can track down the word in Webster's 1828 ("Income" is the gain that proceeds from labor, as opposed to compensation for labor), or you can take as your guide numerous holdings of the U.S. Supreme and appellate Courts, which have made several stabs at clarifying the traditional meaning of what constitutes income for purposes of taxation. I'm including a couple of definitions below. These cites can appear quite convoluted to those unused to reading case law, and if all this is new to you, you'll have to completely flush from your brain any preconceived idea of what "income" means or you will drown in cognitive dissonance. I'll try to keep it simple, but if you're up to it, you can explore the topic further here and here. Since these short quotes are excerpts from much longer citations, I'll try to give a concise translation as to their contextual meaning:

Whatever may constitute income, therefore, must have the essential feature of gain to the recipient...If there is no gain, there is not income...Congress has taxed income, not compensation. -Conner v. U.S., 303 F Supp. 1187 (1969)Translation: Income is not the direct compensation one receives in exchange for labor (i.e. wages); income is the gain one has after expenses.

It is not salaries, wages, or compensation for personal services that are to be included in gains, profits, and income derived from salaries, wages, or compensation for personal services. -Lucas v. Earl, 281 U.S 111 (1930)Translation: salaries and wages are considered compensation for personal services. They are not gains, profits, or income. Gains, profits, and income are derived from wages. That is, after you have received your wages and deducted your basic expenses from those wages, that money you have left (the gain derived from your wages after expenses) is your actual "income."

Still with me? Okay. So for the purposes of paying tithing, how do you know how much of your earnings count as going toward basic expenses in order to arrive at the proper amount for determining your income, which is the part of your earnings you'll pay tithing on?

Well, that's between you and the Lord. In that 1970 letter from the First Presidency (the most recent official pronouncement we have on the topic) we read, "We feel that every member of the Church should be entitled to make his own decision as to what he thinks he owes the Lord, and to make payment accordingly."

That's a wise statement, because only the Lord truly understands your circumstances. Since everyone's situation is different, no one -no bishop, stake president, or general authority- is empowered to tell you how much of your money you should pay tithing on. That's what prayer is for. You make your decision and take it to the Lord for his approval. If you feel right about your decision, you are a full tithe payer as long as you give ten percent of the amount you consider your interest to be. You can fool yourself, but you can't fool the Lord. So be honest with yourself.

I'll tell you how I figure it for our household. At the first of the month I pay my fixed expenses: rent, utilities, phone, and so on. After that I usually have about six or seven hundred dollars left for the two of us to live on. Most of that will go for groceries, but also gas and sundry other things. Emergency car repair and other unexpected contingencies. Maybe a fast food meal here or there. Whatever. Essentially, it's everything we have left over after paying our bills.

Some of this money I will give away to those in greater need than we are, which may amount to a couple hundred dollars or so a month. You may feel it works better for you to budget a certain amount for charitable giving at the beginning of the month and include that in your upfront expenses, and that's fine. I doubt the Lord cares if the Church gets a little less tithing because you've earmarked a chunk of it to his poorer sons and daughters. But we have decided not to limit ourselves to a set amount for giving, so that comes out of our grocery money as we go along, because, well, it's grocery money for somebody. Besides, I'm afraid that if I were to limit my charitable giving to a set amount, I might find it too easy to make excuses to myself that I've already done my share -the way I used to rationalize passing up the needy because I had already paid so much in tithing.

So as far as money for the needy goes, I hand it out as I come across a need, that way I don't have to think about how much I'm giving up. I'm no angel. I have always had a tendency toward greed. So in making this rule for myself of never passing up an opportunity for giving, I don't have to think about what it's costing me. I just do it.

So that whole pool of leftover money is what I choose to consider my surplus/overplus/increase/interest/income, so if it adds up to say, $700, my share of tithing for the Church would be $70.00. That's much less a percentage of my wages than I used to give to the institution most of my life, but it is the proper one, as it leaves me plenty left for the Lord's purposes.

Now, most people would count groceries as part of their basic living expenses, and of course they are, but I don't bother creating a separate budget for groceries. Too complicated. After all, if I wanted to become Pharisaical about it (or obsessive compulsive-take your pick) I could start nitpicking about what it really costs to provide my basic needs. When you get right down to it, I could survive on flour and corn meal, or even locusts and honey, which would increase my titheable surplus, therefore making me an A-Plus First Rate Tithe Payer Guy, but it would make for a very unhappy quality of life.

So I just pay my bills upfront like a responsible adult, then I try to make the rest of my money last as long as I can until it's gone. So lumping my grocery money in with the rest of my walking around money and calling it all surplus is my way of choosing easy. Knowing that we're going to be needing most of what we have left for food keeps me from doing anything stupid with it.Wine, women, and song will have to find themselves some other benefactor.

You can probably tell that if I were to deduct gas, groceries, and necessities upfront, I would probably have little or no surplus at all. On the other hand, I could have counted my monthly internet fee as discretionary, so it works itself out. There may be areas in which you can find a surplus you hadn't thought of. Think of what your family needs to actually survive, and those bills you absolutely have to pay each month, and count everything else as your interest. Some people spend more than I might think they need to on clothes, for instance, but maybe they justify it because they need to wear better clothes to work than I do. Some of what you might call legitimate expenses might seem extravagant to me, but that's why I'm not your judge.

Here in California it's quite easy for some folks to spend close to two hundred dollars on their cable and internet services if they were to buy the whole package. If that's you, you might remove that from the "expenses" column and count that money as part of your discretionary surplus, and therefore money you would tithe against.

Then again, you may feel having cable with all the premium channels is a basic necessity of life. It's your call. If you can justify that to God, fine with me. He's the only one you have to answer to. Even still, recognizing that your $200 cable addiction is not quite a necessity doesn't mean you will have to live without it. It simply means you should maybe count $20.00 of that toward your tithing.

Many married couples cannot agree on what constitutes expenses vs. interest, so don't ask me to figure it out for you. Take it to the Lord in prayer and ask him what he would have you do. If you are a full tithe payer in the eyes of the Lord, that makes you a full tithe payer, period.

My Testimony Of Tithing

As a teenager and young adult growing up in the church, I had a powerful testimony of tithing. I knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that as I continued to faithfully donate ten percent of my gross earnings to the Church, the Lord would continue to bless me with a job I liked and could advance in. And it seemed to be working out.

Looking back, I now recognize that it wasn't really the law of tithing I had a testimony of, since I had never even read the thing. What I really had was the testimony of a movie.

In Seminary we were shown a Church film, "The Windows of Heaven" which told the story of Lorenzo Snow's speaking tour to St. George and environs in the year 1899. The Church was experiencing deep financial trouble; tithing receipts were way down and the deficit was out of control. On the wagon trip to St. George, President Snow's party frequently passed dead and dying cattle along the way. There had been a severe drought in the area, and along with the weight of the Church's financial problems, President Snow was burdened with concerns about how the Church could possibly manage to assist these poor people in their time of trouble, since the Church was broke.

Arriving at the St. George chapel old, weak, and frail, President Snow was helped to the stand and began to give his talk. Suddenly, right in the middle of a sentence, he paused and looked at the back of the chapel as if in a trance. He was silent for a very long time, just staring straight ahead. When he finally resumed speaking, he straightened up and spoke in a mighty voice of authority, calling the congregation to repentance for their failures in paying their tithing, and then dramatically declared:

"... observe this law fully and honestly from now on, you may go ahead and plow your lands, plant your seed, and I promise you in the name of the Lord that in due time clouds will gather, the latter rains from heaven will descend, your lands will be watered, and the rivers and ditches will be filled, and you will yet reap a harvest this very season!"Then followed a montage of Saints faithfully paying their tithes of crops and chickens to the local bishop. Within weeks, rain clouds formed and the windows of heaven literally opened and poured down rain, rain, and more rain! Water filled ditches, resevoirs, ponds, and creeks. The farmer's land was redeemed! The crops were saved! The drought was finally over, and there was much rejoicing.

This movie made quite an impression on my young mind, as it was designed to. The clear message of the film was that anything that may have been going wrong in my life at the time could probably be traced to the fact that I hadn't been faithful enough about paying a full tithe on every dollar I brought in. I was further made to understand that if I were to remain a full tithepayer from then on, the Lord would bless me and I would know nothing but success in life from then on out. All I had to do was never forget to pay my indulgences.

I took the message of that film as it was meant to be taken; that if I did my part I would reap great material rewards. I believed this with all my heart, and on my mission I bore repeated testimony to the incredible benefits that attached to being obedient to the law of tithing. If there was anything I had a testimony of, it was this tithing thing. It was almost my trademark. I was still motivated by the message of this film years later, long after things fell apart for me financially. For years and years I continued to believe wholeheartedly that I would receive bounteous blessings for paying my tithing, even when those blessings never seemed to come.

I had misunderstood the message of the film, you see. Or rather, the film was deliberately crafted to convey promises of blessings that neither the Lord nor Lorenzo Snow had ever made.

The film was an incredible inspiration to me. But what the film did not do was tell the whole truth. As Jay Bell writes in his piece The Windows of Heaven Revisited, "an interesting mixture of fact and fiction characterizes the faith-promoting focus of the film."

First off, the viewer is given the distinct the impression when watching this film that it was somehow the faithlessness of the members that was to blame for the Church being in such dire financial straits. In reality, most of the fault was the result of poor management decisions within the Church leadership at Salt Lake. A good part of the problem, of course, was that the United States government had seized temple square and everything owned by the Church valued above $50,000. But even without the government's "help," the Church hierarchy, prior to Lorenzo Snow taking office, had created more than their share of problems that were now putting the the very survival of the Church in jeopardy. Jay Bell reports:

First, the Church had overspent itself for some time. Wilford Woodruff, anxious to complete the Salt Lake Temple in his lifetime, had spent $1 million to complete the $4 million edifice in 1893. Educational and civic responsibilities also drained the budget. The Church was supporting Young College in Logan, Brigham Young Academy in Provo, and the Latter-day Saint College in Salt Lake. The national depression from 1893 through the latter half of the decade had increased the number of Saints in dire need of welfare. Furthermore, the Church invested heavily in local power, mining, sugar, and salt companies, trying to stimulate regional employment. According to Michael Quinn, the primary cause of the Church's indebtedness was "massive losses in the Church's interlocked mining, sugar, real estate, banking, and investment firms." As early as 1893, the Church began borrowing to meet its obligations, first from stake presidents and eventually from such "outside" institutions as Wells Fargo & Co., and National Union Bank.

Second, the Church maintained little fiscal supervision. Snow had been alarmed, on assuming the presidency, to discover that no budgetary controls existed. Decisions about using Church funds were made ad hoc on an as-needed basis. (Journal of Mormon History, Volume 20, No. 1, 1994)Third, tithing receipts were down, and they had been down ever since the Quorum had changed the rules without authorization from God back in August 1844, when they announced the requirement of a tenth of all one's posessions at baptism, another tenth of all possessions upon arriving in Utah, and a perpetual tenth every year thereafter. Many members contributed only as much as they could afford, and a good number just gave up and stopped trying altogether. And of course, there was that little practice of the Brethren "borrowing" tithing funds for their personal use. The Church was in need of a tithing reformation, and Lorenzo Snow was the right guy at the right time.

Snow cancelled the requirement to give a tenth of one's property at baptism. Henceforth, tithing would consist of one tenth of one's annual income (and yes, everyone at the time knew what "income" was). Tithing receipts immediately and dramatically increased. He instituted strict controls and oversight to eliminate tithing being justified to increase allowances to members of the quorum.

Of course, none of that was mentioned in the movie. An actual liberty taken by the movie was the idea that Lorenzo Snow called the people of St.George to repentance for slacking off on their tithing payments. On the contrary, according to newspaper accounts, "his remarks were mainly eulogistic of the people of this section of the country of their tithes and offerings, giving them the name of being the best tithe-payers and most faithful stake in the Church." (ibid, pg 63)

And though he did speak about tithing, Snow exhibited no dramatic revelation received in the middle of his talk, and he did not promise rain if the people would pay their tithing. In fact, contrary to the main message of the movie, there was no connection made whatsoever between the drought and tithing. Good thing, too, because it would have been embarrassing. There was a little bit of rain here and there over the next three years, but the drought cycle didn't end in St. George until 1902.

Nothing President Snow said in his talk concerned promises or blessings or windows opening or rain coming down or rivers being filled or harvests being reaped. His remarks all centered on what the Lord had said in Section 119: that unless the Saints were willing to properly observe the law of tithing, they would not be found worthy to be a Zion people. Snow stressed this point over and over in all his speaking engagements throughout his tour of Southern Utah, and again in Idaho and along the Wasatch Front after he returned home.

If parents would teach their children to pay tithing, he promised, "then we will have a people prepared to go to Jackson county." He declared that the Christ was coming soon but that the Church congregation would "not hear the voice of God until we pay [a] full tithing and return to Jackson County." Lorenzo Snow clearly understood the meaning of the law of tithing, even if those who commissioned the film about him did not.

So I had been tricked. Once again a movie "based on a true story" had manipulated me into believing something that simply wasn't so.

I understand dramatic license, but was it necessary to change the very moral of the story? Rather than be upfront about how Lorenzo Snow had cleaned up the financial abuses coming out of Salt Lake that had contributed to the deficit, and showing how he motivated the Saints to become re-enthused about the payment of tithes, the 20th century Church leaders who oversaw the production of this movie felt it necessary to get the audience to come to a completely false conclusion. It was the old "Blessing Bait & Switch," the presumption those in power seem to have that we will only come around if they can sell us on the idea that there is something in it for us.

Why is it, I wonder, that Church leaders seem to think we have to be bribed with the promise of future blessings to get us to observe this law in its simplicity? Isn't it enough that God gives us His instructions? Are we children, who must be coddled and coaxed with promises of of toys and candy in order to get us to do the right thing?

There was, of course, a very good reason why the Church rushed this film into production when it did. In 1961 the LDS Church found itself once again on the very brink of bankruptcy, this time due to another rash of stupid investments. The only thing that would save the Church was more tithing; lots of it, and fast. What better way to raise the needed funds than to schedule church-wide showings of a movie designed to inspire the membership to open their wallets and purses like never before?

But instead of telling the story straight, which would have been inspiring on its own merits, the Brethren wanted to make sure the members were given a promise the Lord himself never gave: if you support us, you will be rewarded.

I wonder why it is that in every talk I hear about tithing from the Brethren, the speaker seems to think I won't respond unless he dangles a carrot in front of me? They constantly promise us blessings if we pay our tithing, and lately they have been hinting that if we pay more than a tenth we can expect even more blessings. Almost every time I hear a talk about tithing, the speaker is fudging or prevaricating in order to entice me into obedience. And if you don't think some of the Brethren are above lying outright in order misrepresent the law of tithing, then I suggest you take a look at this piece. Scroll down to Appendix B to follow Apostle Jeffrey Holland's deliberate attempts at subterfuge.

I don't know about you, but for me, simply having the desire to do the Lord's will is enticement enough. I shouldn't have to be bribed and babied along. No wonder there is a groundswell of cynicism within the church about all this. And if you scratch an ex-Mormon, you'll likely find endless tales of deprivation and broken promises beneath.

Time For Another Tithing Reformation?

Lorenzo Snow hated debt and he hated that the Church was in debt. He himself bore no responsibility for the Church's former years of profligacy, but he was the first to admit that Church leadership as a whole was largely accountable for the current mess. Snow presided over the cleanup at Church headquarters, initiating what has been called a Tithing Reformation. As the members recommitted to doing their part, Snow made sure the books were transparent. The members were given a full accounting every April as to what their tithes were being used for, so they could voice approval and give their consent as required by D&C sections 26 and 104.

This practice of financial transparency continued until the late 1950's, when First Counselor Henry Moyle's reckless and embarrassing spending spree brought the Church once again to the brink of bankruptcy. (Tellingly, it was only when it was discovered that there might not be enough money on hand to make payroll that the Twelve suddenly pricked up their ears and started paying attention.)

Ever since that close call, the leadership in Salt Lake has stubbornly refused to provide financial accountability to the members, hiding behind the excuse that, this being the Lord's money, it should be of no concern to the meek and lowly members how the Lord decides to spend it. For over half a century, and in direct defiance of God's clear instructions, the leadership of the Church has kept the membership -the very people who provided the tithes in the first place- completely in the dark as to how those tithes were used. Those who have control of the funds remain accountable only to themselves.

But Church funds are not the special province of the leaders, they belong to the church community as a whole. They are only held in trust by the leaders, who have been specifically directed not to keep the Church's financial dealings secret from the members. As Paul Toscano, former Associate Editor at the Ensign Magazine wrote way back in 1991:

We are likely to be told that if we believe our leaders are called of God then why don’t we trust them with the church’s wealth? This question, however, can be turned around: If we are the people of God, why can’t we be trusted with an accounting? Trust, I suspect, is not the real issue here. The issue is control. Church leaders are like many of our parents and their generation who believe that their children should know little or nothing about the family’s finances. The problem with this view is that our leaders are not our parents. We have heavenly parents. Our leaders are our elder siblings, who, it seems, are tempted to generate policies that tend to lull many of their more compliant brothers and sisters into complacency, inexperience, and unhealthy dependency. (From "Silver and Gold Have I None," Chapter Six of The Sanctity of Dissent.)A growing number of members are now beginning to wonder if it is not past time for another Tithing Reformation.

But if we are to have such a reformation, the Church is going to need a hero like Lorenzo Snow. Good luck finding one. Today there does not seem to be anyone numbered among the Twelve who possesses Snow's caliber of character and leadership. By and large, those running the Church today are descended from the legacy of Eldon Tanner, who took over Church finances and brought with him a team of corporate lawyers and managers whose experiences in the the world of corporate finance have been credited with turning the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints into one of the most successful institutions on earth, religious or otherwise. But if you're looking for another Lorenzo Snow in this group, you may have to look harder. Maybe there's someone coming up through the ranks of the Second Quorum of the Seventy, I don't know.

When we hear about tithing these days, we don't hear the things Lorenzo Snow taught about God's divine law. What we hear from this bunch usually consists of lectures on how we little people need to work harder and contribute more of our share. Meanwhile, much of what we have already donated has been given over to "investments," with the profits derived therefrom used to build lavish hotels and shopping centers -hardly what one would think of as appropriate uses of sacred funds. We watch as the men called to serve us are driven about in limousines provided by our tithes, with full time chauffeurs paid for with our tithes, yet when we complain that we don't have enough gas money to get ourselves to work, our concerns are dismissed with admonishments to have more faith and pay more tithes so that the Lord will bless us with abundance as he has blessed them.

A growing number of Saints are beginning to ask themselves if it is appropriate to continue to tithe for the support of servants who refuse to be accountable to the people they serve. They wonder if it might not be more appropriate at this time to tithe directly to the Lord, rather than to the institutional Church.

These are valid questions, and ones to which I don't have answers. It seems clear from a reading of section 119 that the tithes are to be given to the Church, but on the other hand, if the tithes are not being used as intended, has the law been nullified? Are we then free to give our tithes where we feel they will be put to better and more responsible use? In addition to being a procedural law, section 119 also appears to be a covenant. If the leaders have broken the everlasting covenant (as the Book of Mormon prophets foretold they would) maybe now all bets are off.

Let's look at the scoreboard. While it's true that our tithes continue to be used for the construction of temples around the world, many of the temples already finished are not being used to capacity. Reports are that there are not enough visitors in some temples to hold regularly scheduled sessions. And then there is the catch-22 that bars members who have not paid a full tithe from entering the temple. (Not a policy based on doctrine, by the way, but only a whim once expressed by John Taylor that morphed over the decades into an ironclad rule.) As fewer members elect to provide the amount of tithes the modern leaders insist upon, there will be fewer members attending the temples, and thus less need for more temples to be built.

As for tithes being used for "the laying of the foundation of Zion," it's anybody's guess whether that is still held up as a priority. Once again, we would know if only the leaders provided us with a yearly report. What we do know is that members living in other countries are now instructed not to gather to Zion, even though the imperative to do so is a primary article of our faith.

There is not much question about whether some of our tithes go to "pay the debts of the presidency of [the] Church." From all appearances, the tithes appear to cover that, and then some.

I personally know several devout members who continue to recognize the importance of paying a faithful tithe, but do not feel compelled to deliver those tithes to the corporate Church at this time. They choose instead to disburse their tithes where they feel that money will do the most good. That might mean giving directly to individuals in need, or it might be given to a food bank or other group that is directly involved with assisting those less fortunate.

Certainly Latter-day Saints can contribute as much as they desire to the Fast Offering fund, but even there we have reason to wonder if any funds contributed to the Church for a specific purpose will end up where the giver intended. By now most of us are aware of the disclaimer at the bottom of the new donation slips that notifies the giver that the Church reserves the right to put your money to whatever use the Church decides.

If you prefer your tithes end up in the hands of fellow Latter-day Saints, I have been hearing good things about the Liahona Children's Foundation. One of my friends is heavily involved with this outfit, and he does a lot of good through it.

I find it unfortunate that large numbers of Latter-day Saints have stopped tithing completely, either to the Church or to anyone else, due to their frustration with current Church policy. That's why I applaud those who still feel a desire to pay a tenth to the Lord in whatever way they choose. My wife and I have been the recipients of some of these newly directed tithes, and, as I documented in my previous post, I felt no shame in accepting them with gratitude and thanksgiving.

We have never personally met any of the people who gave us that assistance. Every single one of them was unknown to us; strangers, every one. But at the time those much needed funds were delivered into my hands, I was privileged to feel an indescribable, palpable connection of the spirit between these givers and myself that at the time I was unable to put my finger on, or adequately understand. I think I can explain it now.

When we join together in the service of each other, sometimes we will be the givers, and other times receivers. But even as strangers, if we lift each other up, we become part of a renewed community of one in Christ. The way Paul the Apostle described it was that we were now "no more strangers and foreigners." I now know how to describe what that feeling was that connected me and Connie to those distant brothers and sisters who raised us up in their love. It felt like Zion.

[A note about leaving comments: Many readers have posted as "Anonymous" even though they don't wish to, only because they see no other option. If you don't have a Google, Wordpress, or other username among those listed, you can enter a username in the dropdown box that reads "Name/URL." Put your name in the "Name" box, ignore the request for a URL, and you should be good to go. I have a pretty firm policy of never censoring or deleting comments,so if your comment does not immediately appear, it probably means it is being held in the spam filter, which seems to lock in arbitrarily on some posts for reasons unknown. If you have submitted a comment and it doesn't immediately show up, give me a nudge at [email protected] and I'll knock it loose. -Rock]

Update, December 14, 2012:

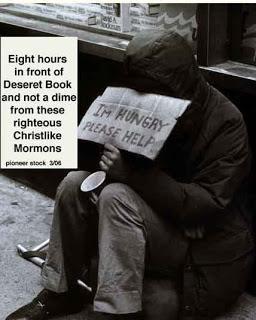

In light of the controversy stirred up by reader Weston Krogstadt, who objects in the comment section below to my use of a certain photograph, another reader has kindly provided a "corrected" version of that picture. I trust this revised photo will meet with Brother Krogstadt's approval.