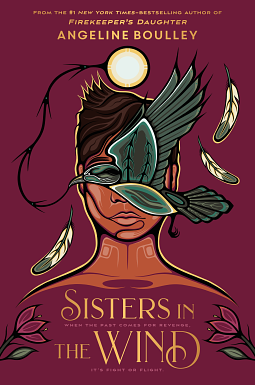

Angeline Boulley has done it again. She’s written a story that’s hard to put down, but is also steeped in Native issues and history, with characters that are emotionally complex. And if you’re looking for a book that picks up the lives of the main characters in Firekeeper’s Daughter, you won’t be disappointed. This is a standalone book, but if you haven’t read the previous two, I recommend reading them first.

Lucy Smith was raised by a single father who told her nothing about her mother’s Native heritage. When he died, she was placed in a series of foster homes. Now at 18, she’s on the run, placing her life and the lives of those she gets close to, in jeopardy. When a Mr. Jameson shows up at her workplace offering to reconnect her to her mother’s family, her first impulse is to run, as fast as she can.

While Firekeeper’s Daughter explored drugs and criminal justice for Native populations, and Warrior Girl Unearthed explored the looting of Native graves and selling of artifacts, this book explores the Indian Child Welfare Act, a law passed in 1978 to keep more Native children in their tribal communities. The Act is designed “to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families by the establishment of minimum Federal standards for the removal of Indian children and placement of such children in homes which will reflect the unique values of Indian culture.” In other words, it recognizes that Native children benefit from connections with their culture and family and prioritizes such placements.

An engaging thriller, Boulley also explores issues in the child welfare and adoption systems, which historically have separated children from Native families. Lucy is told by a social worker that her possible native heritage will only complicate things, so she’s never given an opportunity to learn where she comes from. She only knows that her mother gave her up willingly. She loved her father, so she’s hesitant to explore her mother’s history. But she’s alone, and in danger.

Having worked with a foster care program, I was grateful that Boulley included at least one foster care setting that was not abusive. I know there’s plenty of abuse out there, but I also know there are good foster care homes where children are cared for. I hope people don’t come away from this story, or others, with the idea that all foster homes are corrupt.

I appreciated the slow building of Lucy’s relationships with Daunis and Jamie. Lucy has lots of reasons not to trust them, and it’s interesting that she’s able to bond more quickly with Jamie than with Daunis, because she sees Daunis as representing the mother who abandoned her and needs time to be ready to accept her Ojibwe heritage. I also loved the way Boulley integrates Ojibwe language and cultural practices throughout the novel. Since Jamie and Daunis need to explain these to Lucy, it’s educational for the reader as well.

I liked the theme of fire and ash that recurs – fire is both a destructive force and a spiritual one. Lucy’s first foster parent describes fire as “speaking to the chaos within us”. One character is described as a “gas can looking for a match”. When Lucy loses her temper with Jamie and Daunis:

The instant the words leave my throat, I wait for the relief. The anticlimactic part when the top of the volcano blows into the sky and the hot wind carries the ash far away. Instead I’m a pyrotechnic flow of regret.

In contrast, fire is an important symbol in Ojibwe ceremonies, present during the four-day mourning period after someone passes away and travels to the next world. Her father’s friend Abe Charlevoix describes fire as a means of communicating directly with the spirits. And in a more practical sense, tribal communities understood that while destructive, fire is a force that needs to be managed.

Arguably, Boulley’s use of fire as a plot device is a bit heavy-handed – fires follow Lucy wherever she goes. But that’s a minor issue.

It’s entirely coincidental that I read this right after The Berry Pickers, a novel in which a four year old Mi’kmaq girl is taken from her family and raised without any information about her birth family and heritage. Like Lucy, Norma is occasionally asked if she’s Native but she’s always been told she is not. While the situations in these two novels are quite different, both are an exploration of cultural and racial identity, and the importance of knowing where we are from. I recommend both books, though I liked Sisters in the Wind more. I was somewhat frustrated with the slow pace and inaction of the characters in The Berry Pickers, though I won’t say more about the plot to prevent spoilers.

As with Boulley’s other books, I loved everything about this one, and will happily recommend it to everyone I know. Her writing is great for teens as well as adults, though it’s often classified as YA. It deals with very heavy subjects, but it’s also a book you’ll have a hard time putting down.

Note: I received an advanced review copy from NetGalley and publisher Macmillan/Henry Holt and Company. This book published September 2, 2025.