Russian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky (1962-2017)

Russian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky (1962-2017)In Memoriam

With the old year winding down and the new Metropolitan Opera broadcast season gearing up, let me pay tribute to some of the classical music artists, singers, musicians, and craftspeople who have passed on to their heavenly reward. I have broken them out based on voice category or their specific field of endeavor:

ANNOUNCER

Peter Allen (September 17, 1920 – October 8, 2016) was the Met Opera’s radio host for 29 seasons, starting in January 1975 after the company’s longtime announcer, Milton Cross, had suddenly passed away after 43 years of service. I remember both Cross and Allen, and between them there were lots and lots of opera talk, not to mention the knowledge imparted about those works. To me, Cross almost always came across as pompous and aloof, a byproduct of an earlier era of radio journalism. But with Allen (born Harold Levy in Toronto, Canada), there was a gentlemanly manner and easy affability about him, along with a natural Canadian reserve. A most erudite individual, Allen became a radio announcer upon graduation from Ohio State University, eventually moving to New York and serving as radio station WQXR’s classical-music announcer from 1947 until his retirement. He went on to earn a reputation of grace under fire, of composure and imperturbability in the midst of chaos. His smooth delivery and soothing fireside style were never grating or perturbing, a true professional in every way. And Allen absolutely adored opera. I will never forget how he delivered Tosca’s last line in Act III, just before she leapt to her death — conveyed to worldwide audiences in a most unassuming manner. With bite as well as no small degree of bemusement, Allen spoke the fabled words: “Scarpia, we meet before God!” You could almost see the announcer grinning behind his bespectacled bearing. Allen stepped down in September 2004 when Margaret Juntwait was chosen to replace him.

CONDUCTORS

Neville Marriner (April 15, 1924 – October 2, 2017) and Georges Prêtre (August 14, 1924 – January 4, 2017) had overlapping podium careers. Born four months apart (Marriner in the United Kingdom, Prêtre in France), they both started playing jazz at an early age. In addition to being an accomplished violinist, Marriner studied at the Royal College of Music in London, while Prêtre, who preferred the trumpet, took up the conducting art at the Paris Conservatory. Prêtre led his first opera at Marseilles in 1946. The work was Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila, which he recorded in 1962 with tenor Jon Vickers, mezzo Rita Gorr and baritone Ernest Blanc. Not necessarily an opera conductor but known primarily for his founding of the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields (a chamber ensemble at its start), Marriner achieved worldwide fame and recognition with the soundtrack to director Miloš Forman’s 1984 film of Peter Shaffer’s play Amadeus. Throughout the years, Marriner’s Mozart recordings with the Academy of St. Martin’s have won numerous Grammy Awards as well as other distinctions. Prêtre continued to work with various orchestras throughout his lengthy career. Fans of soprano Maria Callas will recall his podium presence for her various comeback concerts and recital albums, including an EMI/Angel Records stereo remake of Tosca featuring her frequent onstage co-star Tito Gobbi and tenor Carlos Bergonzi; and a marvelously atmospheric recording of Bizet’s Carmen (which Callas never sang on the stage) with the late Nicolai Gedda (see below).

Jeffrey Tate (April 28, 1943 – June 2, 2017) was a physician by training (he was an eye specialist at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London) before becoming a musician. Tate overcame two childhood ailments, congenital spina bifida and kyphosis (curvature of the spine), in order to devote full-time to medicine, although he remained undecided about a career for some time. He eventually abandoned medicine for music around 1970-71, studying at the London Opera Centre and then at Covent Garden. Some of his early conducting mentors were Georg Solti, Colin Davis, and Josef Krips. A chance meeting with conductor and avant-garde composer Pierre Boulez led to Tate’s appointment as Boulez’s assistant at the 1976 centennial production of Wagner’s Ring cycle at Bayreuth. He was later offered a position in Cologne, where after much cajoling he was persuaded to conduct Carmen in Sweden. This led to further engagements throughout Europe, conducting Mozart’s The Magic Flute and Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann. Tate made his Metropolitan Opera debut in 1980, leading a revival of Alban Berg’s Lulu, a historic production which included the restored third act. Primarily a conductor of the classical repertoire — he was chief conductor of the Hamburg Symphony Orchestra since 2009 — Tate spent much of his time in the opera houses of Europe and England and giving concerts, especially in Germany where he made his home. He passed away of a heart attack at an orchestra rehearsal at the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, Italy.

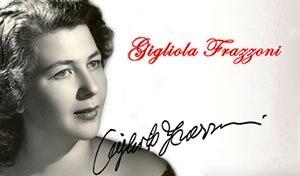

SOPRANOS

Gigliola Frazzoni (February 22, 1923 – December 3, 2016) was born in Bologna. She studied with former diva Blanche Marchesi and, according to Frazzoni’s Official Website, made her professional debut on October 4, 1947 in the minor role of Samaritana in Zandonai’s Francesca da Rimini. Frazzoni was a lyric soprano with a strong dramatic flair that endeared her to Italian audiences. Because of her fear of flying, Frazzoni’s career was limited to the European Continent, specifically to Italy, France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Ireland, and Egypt. Although it limited her exposure abroad (she made few studio recordings), Frazzoni can still be heard as Minnie in Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West in a live 1956 transmission from La Scala, alongside colleagues Franco Corelli and Tito Gobbi, and conductor Antonino Votto. Radio commentator Ira Siff’s review of the recording for Opera News emphasized that “Frazzoni’s Minnie fairly leaps out of the speakers; her fragility, courage, longing and despair tug at the heart of the listener.” Americans never got to hear the singer in her prime. However, this recorded memento of her art remains a testament to the fire and viability of Italian verismo and one of its chief proponents.

Roberta Peters (May 4, 1930 – January 18, 2017), Patrice Munsel (May 14, 1925 – August 4, 2016), and Brenda Lewis (March 2, 1921 – September 16, 2017) all made their Metropolitan and/or professional debuts within a few years of each other. Brenda Lewis (born Birdie Solomon), the oldest of the group, first appeared as the Marschallin in Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier at the Philadelphia Opera in 1941. She became a mainstay at the New York City Opera for 22 seasons (from 1945-1967), while her Met Opera debut took place on January 24, 1952 as Musetta in La Bohème, opposite Brazilian soprano Bidu Sayão. A versatile artist encompassing a wide range of styles and vocal demands, Lewis made her mark in two important American works, Marc Blitzstein’s Regina and especially Jack Beeson’s Lizzie Borden, as well as in musical theater (Call Me Madam, Kiss Me, Kate, and Annie Get Your Gun). Patrice Munsel (née Munsil), the second oldest, was the youngest singer ever to have debuted at the Met, taking on the coloratura part of Philine in Thomas’ Mignon at age 18, on December 4, 1943, when most teenagers of the time were graduating high school. Munsel was a popular crossover artist, enjoying a fulfilling second career in musical comedy, along with television forays and Broadway road-show outings of Mame and Applause. Her final appearance with the Met was in Offenbach’s La Périchole on January 28, 1958. Peters (real name Peterman), the youngest of the three, debuted at the Met on November 17, 1950, as a substitute Zerlina in Mozart’s Don Giovanni. She was two years older than Munsel was at her debut. In all, Peters’ career at the Met lasted a total 34 seasons, with her final performance as Gilda in Verdi’s Rigoletto occurring on April 12, 1985. It was an early Rigoletto performance with a handsome young baritone named Robert Merrill that caught Peters’ eye as well her ear. They were married in 1952, but the union did not last: they realized they were much too young at the time. “I think I fell in love with his voice,” she later recalled, “not with the man.” However, Peters and Merrill remained close friends for many years thereafter. In fact, one of the baritone’s frequent collaborators, tenor Jan Peerce, introduced Peters to voice coach William Herman, who was Patrice Munsel’s teacher. Another colleague and close friend of Merrill’s, tenor Richard Tucker, who often played the Duke of Mantua to Peters’ Gilda, sang alongside the soprano in 1967 at the start of the Israeli Six-Day War.

Géori Boué (October 16, 1918 – January 5, 2017), born Georgette, was a French lyric soprano of wide-ranging roles during the pre- and postwar years, beginning with her debut at the Capitole de Toulouse as the page Urbain in Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots. Boué became familiar to French and Western European audiences with her assumption of Gounod’s rarely heard Mireille, Massenet’s Manon, Charpentier’s Louise, Micaela in Carmen, Debussy’s Mélisande in Pelléas et Mélisande, and copious others. She toured the cities of Spain, Mexico, Brazil, Italy, and Germany, often appearing in tandem with her husband, the French baritone Roger Bourdin, in such works as The Tales of Hoffmann (Antonia and Dr. Miracle), the aforementioned Pelléas (Mélisande and Golaud), Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin (Tatyana and Onegin), and Gounod’s Faust (Marguérite and Valentin). She was particularly memorable in Offenbach’s operettas, among them La Belle Hélène and La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein.

Roberta Knie (May 13, 1938 – March 16, 2017) was a dramatic soprano especially adept in the works of Wagner. Born in Oklahoma, Knie spent time in London and in Germany with famed tenor Max Lorenz. Her professional debut occurred in Germany in 1964 as Elisabeth in Tannhäuser. She became a member of the Vienna State Opera in the early 1970s and made her Bayreuth debut as Brünnhilde in Die Walküre in 1974. Her first stab at Isolde came a year later in a Wieland Wagner production of Tristan und Isolde at Ravenna. Plagued by illness (viral pneumonia, a detached retina, colon cancer) and disagreements with producer-directors, Knie’s singing career ended in 1991. It was supplemented by a teaching career that began in earnest in 1996; and as an artist in residence in 2004 in the Voice and Opera Department of Temple University. Her Met debut was in 1976 as Chrysothemis in Strauss’ Elektra. Knie bore a striking resemblance to Welsh soprano Gwyneth Jones, who shared similar Wagnerian repertory. Curiously, due to Knie’s frequent battles with director Patrice Chéreau during the run of Bayreuth’s centennial Ring production, she was replaced by Dame Gwyneth.

Carol Neblett (February 1, 1946 – November 23, 2017) was a shining star in the operatic firmament. With her stunning looks and impressive stage deportment — not to mention her lithe figure — Neblett attracted immediate attention from the start. That she had a voice to match made her a much sought-after artist. Another early starter, Neblett made her professional bow in 1964 at age 18 in Respighi’s Lauda per la Natività del Signore (“Laud to the Nativity of the Lord”). Known for “her charming, often sensual portrayals of comic characters and dramatic heroines,” Carol was married to conductor Kenneth Schermerhorn. One of her favorite roles was Tosca, which she sang over 400 times (in her estimation), including performances at the Chicago Lyric with Luciano Pavarotti. Neblett also appeared as Puccini’s other forthright heroine Minnie in La Fanciulla del West at Covent Garden with Plácido Domingo (she later recorded the role with Domingo, Sherrill Milnes and conductor Zubin Mehta). Her New York City Opera debut came in 1969 as Musetta, a natural fit for her sparkling personality. That same year she took on the challenge of both Margherita and Elena (Helen of Troy) in Tito Capobianco’s production of Mefistofele, with Norman Treigle as the Devil. Neblett also partook of a revival of Monteverdi’s The Coronation of Poppaea (1973), the title role in Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos (1973), and the Frank Corsaro staging of an overlooked masterpiece, Korngold’s Die Tote Stadt (“The Dead City”), with tenor John Alexander. She went on to record the role of Marietta/Marie for RCA Victor with René Kollo. But her biggest claim to fame was a production of Massenet’s Thais in New Orleans, wherein she appeared in the buff. Her Met Opera career started in 1979 with the role of Senta in Jean-Pierre Ponnelle’s disastrous The Flying Dutchman production. Recovering from that debacle, Neblett spent ten seasons at the Met, singing Musetta, Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni, Alice Ford in Falstaff, and Tosca. A bout with alcoholism in the 1990s led to major career challenges, which she managed to overcome by taking up teaching at Chapman University in Southern California.

TENORS

Nicolai Gedda (July 11, 1925 – January 8, 2017). Not only did Gedda have a long stage and recording career, but he was also long-lived in number of years. Born Harry Gustaf Nikolai Gädda (pronounced “Yedda”) in Sweden to dirt poor parents, the young Gedda was raised by his father’s sister and her Russian husband. It was from his step-father that he gained fluency in several foreign languages, along with a healthy respect for music from all genres. While working as a bank teller, one of Gedda’s customers recommended a voice teacher to improve his chances at a musical career. This led to a brief period of study and his formal debut in 1952 as Chapelou in Adolphe Adam’s Le Postillon de Lonjumeau, a part that boasted a high D at his entrance. Gedda’s incredible facility with high notes, in addition to his language ability (to say nothing of perfect diction), opened the doors to a successful career in lyric and bel canto roles. Mozart was on the menu for several seasons, including the roles of Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni, Belmonte in The Abduction from the Seraglio, and Tamino in The Magic Flute. EMI impresario Walter Legge and his wife, soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, heard the versatile singer at the Royal Opera of Stockholm, and in due course a long-term contract was signed. Subsequently, Gedda became an exclusive EMI/Angel Records artist for the bulk of his career. This included a well received recording of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov (in the role of the Pretender Dmitri), alongside Bulgarian basso Boris Christoff. A steady diet of opera, operetta, and light opera roles followed, many with Schwarzkopf as his leading lady and conducted by a who’s who of legendary maestros, among them Herbert von Karajan, Erich Kunz, Otto Ackermann, Thomas Beecham, Lovro von Matačić, Otto Klemperer, Carlo Maria Giulini, André Cluytens, Josef Krips, and others. Before the days of Domingo and Pavarotti, Gedda was the most recorded male vocal artist to have released operatic LPs. His Met debut occurred on November 1, 1957 in Gounod’s Faust, a role he twice recorded. For all intents and purposes, the Met became his home base, but he allowed himself sufficient leeway to appear all over the European Continent. Some of his numerous roles included the aforementioned Don Ottavio, the Duke in Rigoletto, Alfredo in La Traviata, Rodolfo in La Bohème, Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly, Hoffmann in The Tales of Hoffmann, Don José in Carmen, Des Grieux in Manon, Roméo, Lensky in Eugene Onegin, Gherman in The Queen of Spades, Danilo in Lehár’s The Merry Widow, and Anatol in Samuel Barber’s Vanessa in which he was highly praised for his exceptionally fine English enunciation. Although he had a tendency to sharpness above the staff, Gedda was a reliable, indeed extremely dependable artist who always delivered the goods. In his Opera News obit, Peter G. Davis wrote that while “Gedda never generated the hysterical fan response of, say, Franco Corelli … few left his finely nuanced, vocally secure, emotionally generous performances feeling cheated.”

Johan Botha (August 19, 1965 – September 8, 2016) was sadly cut down in the prime of his life by cancer. The South African tenor was known for his “gloriously large voice and physique,” according to the publication The Telegraph. Indeed, that over-sized frame was both a hindrance and a help in his career as a heroic tenor. Luckily for opera fans, the barrel-chested Botha was one of the few modern interpreters of Wagner who could get through a full evening’s worth of Walther von Stolzing’s “Morning Song” or Tannhäuser’s grueling third-act “Rome Narrative” without running out of fuel. Impressive as those accomplishments were, incredibly Botha began his singing career as a bass-baritone! He grew up in a farming community not far from Johannesburg. During his military service (1983-85), Botha was urged to join the choir. It was there that his singing talents were brought to light, although he could hit those high notes from early youth. To ease the tension of military life, he took up percussion and the guitar as a member of the military jazz band. Around 1986 or 1987, his voice changed as he “started moving up into a higher register.” His professional debut came in 1989 in Johannesburg singing Max in a production of Der Freischütz. Heard by Norbert Balatsch, the chorus master for the Bayreuth Festival, he was engaged as part of the chorus. A few seasons later, in 1995, he appeared at the Opéra Bastille in Paris, singing Pinkerton in Robert Wilson’s controversial stylized production of Madama Butterfly. Botha took up residency in Vienna; in 2003, he was made a Kammersänger by the Vienna State Opera. His Met debut took place in 1997 as Canio in Pagliacci. He would go on to sing more than 80 performances of 10 roles in over 20 years with the company. Among his assignments were Radamès in Aida, Otello, Calàf in Turandot, Walther in Die Meistersinger (excellently done!), and a staggering interpretation of Tannhäuser, which to my mind was his finest achievement at the house. Earlier, Botha took part in an unusual 2002 production of Puccini’s Turandot. Directed by David Pountney for the Vienna State Opera and conducted by Valery Gergiev, this was the first performance of the newly revised third act composed by Luciano Berio. Mysterious and modern-sounding, this new ending did not convince listeners or critics of its viability. Despite the hoopla surrounding this event, Botha’s contribution was cleanly and assuredly delivered. The production has been preserved on DVD/Blu-ray Disc for the curious-minded among us. Botha’s size became a barrier for some, but with his characteristic good humor the tenor took the criticism in stride, fueled by a firm religious conviction that all would be right.

Barry Busse (August 18, 1946 – May 15, 2017) and Manfred Jung (July 9, 1940 – April 14, 2017) were near contemporaries who passed away within a month of each other. Their repertoires coincided from time to time, but Busse and Jung were basically vocal opposites. Born in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, Busse received his BA in Music from Oberlin College, a Master’s in Music from the Manhattan School of Music, and a Master’s in Education from Walsh University. He started out as a baritone, winning the coveted George London Award, but switched to tenor in 1977, singing in Carlisle Floyd’s Of Mice and Men in Houston. He was often compared to Canadian powerhouse Jon Vickers, not only in looks but in voice and acting chops. Both Vickers and Busse sang the role of Britten’s Peter Grimes in that self-titled work, as well as Canio in Pagliacci, Wagner’s Parsifal, Siegmund in Die Walküre, and Don José in Carmen. Busse helped to extend the boundaries of the dramatic tenor repertoire by performing in numerous modern works, many of them world and/or American premieres, i.e. in Dominick Argento’s Postcard from Morocco (1971), Conrad Susa’s Transformations (1973), Thea Musgrave’s Mary, Queen of Scots (1980), and David Lang’s Modern Painters (1995) and Nosferatu. Manfred Jung was a German Heldentenor who performed in Wagner’s operas all over the world. Having started out in life as an electrician and lighting technician, Jung then studied music in Cologne where he went on to sing lyric tenor roles in Mozart operas. He made his Bayreuth Festival debut in 1967 singing the part of Arindal in Wagner’s Die Feen (“The Fairies”), the composer’s very first stage creation. From there, Jung put in guest appearances at the Salzburg Easter Festival under Herbert von Karajan and at the Deutsche Oper am Rhein. He is perhaps best known to American audiences for having participated in the 1976 centennial production of the Ring cycle at Bayreuth under Pierre Boulez and director Patrice Chéreau. The revival in 1980 (shown on German TV and broadcast to American audiences via Public Television), where Jung sang the hero Siegfried in both Siegfried and Götterdämmerung, are the ones most viewers will remember. Jung earned the distinction of having sung every one of Wagner’s tenor roles. His tone may have been a tad underpowered for these two massive works (in this author’s opinion), but his wondrous acting talent opposite Donald McIntyre’s world-weary Wanderer, Heinz Zednik’s crafty Mime, and Gwyneth Jones’ womanly Brünnhilde, was anything but mediocre. In 1981, he made both his Vienna State Opera and Metropolitan Opera debuts.

BASSES

John Del Carlo (September 21, 1951 – November 2, 2016) and Enzo Dara (October 13, 1938 – August 25, 2017) specialized in the bel canto and opera buffa realm. A hometown San Francisco boy, Del Carlo was enrolled in the Merola Program where he learned his craft. He was a regular at the city’s War Memorial Opera House, where he sang many of his money roles — among them Dr. Bartolo in Rossini’s The Barber of Seville and Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, Donizetti’s Don Pasquale and Dulcamara in The Elixir of Love, Don Magnifico and Dandini in Rossini’s La Cenerentola, and other comic parts. He made a specialty out of characters that included the Sacristan in Tosca, Benoit and Alcindoro in La Bohème, and Falstaff in Verdi’s eponymously titled opera. Certainly his towering 6’ 6” height lent stature to these overlooked assignments. He appeared all over Europe and the U.S, and even sang the leading Wagner roles for a time, until he found his true niche in comedy. He famously sang Kothner in Die Meistersinger for then-Met Opera music director James Levine. According to Del Carlo’s obituary in Opera News, “When he finished his audition, Levine said, ‘Bravo, John. Where have you been?’” He made his debut in the part on January 14, 1993 and enjoyed a 21-season career there. Enzo Dara’s career crisscrossed with that of Del Carlo’s: both artists sang pretty much the same buffo repertoire. The difference in his case was that Dara, older than his American colleague by 13 years, was born and bred in Mantua, which gave him an advantage in authentic Italian culture and pronunciation. He worked as a journalist for a time before switching careers. His professional debut came in 1960 as Colline in La Bohème. Dara’s gift for rapid-fire vocal patter and comic timing was leavened by his exceptionally clear diction and sterling musicianship. Indeed, Dara sang with the best of the lot, including Samuel Ramey, Marilyn Horne, Luciano Pavarotti, Hermann Prey, Leo Nucci, Teresa Berganza, Alessandro Corbelli, and a host of others. Dara sang 41 performances at the Met of his signature Dr. Bartolo.

DIRECTOR

Frank Corsaro (December 22, 1924 – November 11, 2017). Along with director Tito Capobianco, conductor Julius Rudel, soprano Beverly Sills, and bass-baritone Norman Treigle, Corsaro was one of the most influential artists associated with the New York City Opera in its heyday. Born Francesco Andrea Corsaro in New York City (actually, on a boat in New York Harbor “that was bringing his immigrant parents from Argentina”), the future Actor’s Studio alumnus and Broadway and NYCO stage director graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, with a short stint in between at Immaculata High School in Manhattan. He attended City College and the Yale Drama School, where his production of Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit paved the way in 1947 for the Off-Broadway movement. From 1950, and between the years 1988 to 1995, Corsaro studied at and directed workshops at the Actor’s Studio, along with serving as its artistic director. He appeared on Broadway as an actor in the 1950s; he also started directing plays, many of which starred such luminaries as Hume Cronyn, Jessica Tandy, Ben Gazzara, Shelley Winters, and Bette Davis. It was Julius Rudel who gave him his City Opera break when Corsaro was asked to direct Floyd’s Susannah in 1958. His drive for authenticity, his inborn rapport with singers and performers, and ability to get to the heart of any opera or play, served him well throughout his years at the company. One of his adherents, baritone Richard Stilwell, remarked in Opera News that “Corsaro had an amazing combination of musical knowledge and theatrical expertise” that opened his eyes “to what opera could be — a special art form in which words, music and theatrical prowess contributed equally to create stirring drama.” That Corsaro did! I was privy to several of his insightful productions, the first of which was a 1975 Faust with Samuel Ramey as Méphistophélès, Kenneth Riegel as Faust, and Carol Bayard as Marguérite. Corsaro brought out Gounod’s dark humor (Faust’s laboratory, in eerie imitation of Leonardo Da Vinci, was littered with cadavers, one of which was Mephisto himself!), as well as the pervasiveness of evil in the everyday world (Act III began with a bone-chilling recreation of a Satanic Black Mass). Another was his modern take on Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, wherein Pinkerton’s naval buddies and their sweethearts were a boisterous presence at the teenage Cio-Cio-San’s wedding. Still another was his tradition-breaking La Traviata, where Alfredo (a very young Plácido Domingo) carried off the consumptive Violetta around the stage in his arms as they sang the third act duet, “Parigi o cara.” This was preceded in Act I by that notoriously long pause between the chorus’ departure and Violetta’s reflection before her aria, “Ah, fors’è lui,” beginning with the line “È strano.” How dare Corsaro interrupt the opera’s forward momentum with this ridiculous silence! But it worked! The performance I saw was a 1974 revival of the 1966 production that featured the fragile and waif-like Violetta of Patricia Brooks and the angry, menacing Giorgio Germont of Dominic Cossa, both veterans of the original. Corsaro’s only directorial misfire, in my recollection, was an ill-conceived Manon Lescaut done-in by over-ambition and miscasting. His other NYCO projects included Pelléas at Mélisande (a big hit with the hippies!), Leoš Janáček’s The Makropoulos Case and The Cunning Little Vixen, Bizet’s Carmen (which I also happened to catch), and Korngold’s Die Tote Stadt in collaboration with artist and filmmaker Ronald Chase. In 1987, Corsaro joined the staff of the Juilliard School’s American Opera Center.

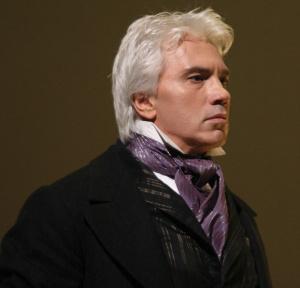

BARITONE

Dmitri Hvorostovsky (October 16, 1962 – November 22, 2017). One of the truly great Verdi singers of his generation, Hvorostovsky (“Dima” to his friends and fellow associates) was born in Krasnoyarsk, Russia — a heavily industrialized area of Siberia. He battled alcoholism and gang participation in his youth. He left behind the squalor of his hometown for an international career in opera. Gifted with a smoldering stage presence, a masculine voice, and a shock of prematurely gray-turned-silver hair which he wore as a badge of honor, Dmitri was the epitome of class and style (no doubt his 6’ 4” frame had something to do with it). I heard his supple tones in many a Met performance, both live and on records, and on DVD/Blu-ray. With his super-human breath control, nobody could sing Rodrigo, the Marquis of Posa, in Verdi’s Don Carlo the way he could. Take, for example, Rodrigo’s death scene with its matchless legato and long-lined expressiveness. An equally fine elder Germont in La Traviata, Count di Luna in Il Trovatore, and Renato in Un Ballo in Maschera, Hvorostovsky excelled in Russian roles: Tchaikovsky’s haughty title character in Eugene Onegin, his Met debut role (1995) as Yeletsky in the same composer’s The Queen of Spades (aka Pique Dame), and his heart-on-sleeve portrayal of the brooding Andrei Bolkonsky in Prokofiev’s War and Peace, based on Tolstoy’s historical novel. His moving death scene, accompanied by the youthful Anna Netrebko as Natasha Rostova, did not leave a dry eye in the house. He was a surprise winner of the 1989 Cardiff Singer of the World Competition, barely beating out Welshman Bryn Terfel for the honor. Hvorostovsky’s passing of brain cancer was a tragic loss. It reminded me of two other giants of the baritone repertoire: American-born Leonard Warren, who died on stage at the Old Met during a performance of Verdi’s La Forza del Destino; and the suave Italian master Ettore Bastianini, who died at 45 of throat cancer. It is fitting, then, that the Metropolitan Opera’s first broadcast of the 2017-2018 season of Verdi’s Requiem should be dedicated to the memory of this beloved artist.

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine.

(Many thanks to Opera News, the New York Times, the Guardian, the Telegraph, Opera Wire, and other publications for providing background information and informative notes)

Copyright © 2017 by Josmar F. Lopes

Advertisements &b; &b;