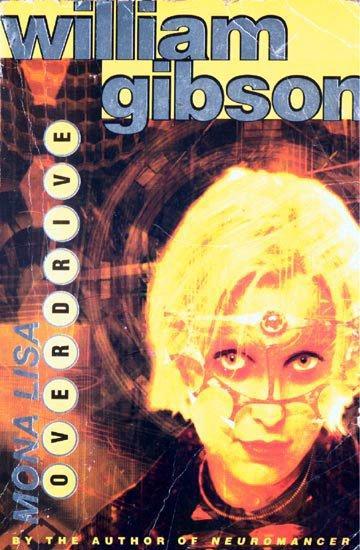

Mona Lisa Overdrive, by William Gibson

Mona Lisa Overdrive is the third book in Gibson’s famous “Sprawl” trilogy, following up on the extraordinary Neuromancer and his somewhat less successful Count Zero.

The key problem with Count Zero is that it’s very much the middle book of a trilogy. The plot doesn’t stand on its own feet, leaving much of what’s going on to be explained or resolved in the next novel. It’s still a mostly rewarding read, but it’s not a standalone work and on its own doesn’t make a huge amount of sense.

Mona Lisa Overdrive provides the resolution that Count Zero lacked, and more than that it makes the whole trilogy greater than any of its individual parts. I still remember being blown away by it when I first read it, and reading it fresh now almost 30 years later I’m still impressed.

The story is set some years since the events of Count Zero, which itself was a few years on from Neuromancer. The book opens with Kumiko, daughter to a Yakuza boss, being sent to London for her own safety. Technology has advanced and she now has an AI in a pocket device, a combination of local guide, adviser and security software. She runs into Sally Shears, who readers recognize as being Molly from Neuromancer now under a new name but just as deadly as ever.

Back in the US a young prostitute named Mona with a marked resemblance to major star Angie Mitchell (from Count Zero) has attracted the attention of some very dangerous and very rich people. Her pimp thinks that this is his shot at making some serious money and plans to trade Mona for a seat at the big table. Mona doesn’t know much, but she knows better than that. When big fish take an interest in little fish, the little fish tend to get eaten.

Angie herself is in rehab. She and Bobby Newmark (Count Zero) are no longer together, and she’s isolated in a world of luxury and people more concerned with her bankability than her welfare. She finds the drug she’s recovering from hidden where she’d be sure to find it, raising a question as to who might want her not to get clean. Angie starts to get concerned that she might be more valuable as a malleable addict than as a free agent with a clear head.

Finally, Slick Henry is a brain-damaged sculptor living in a contemporary wasteland of disused factories and abandoned industrial waste named Dog Solitude. He gets paid by local hood Kid Afrika to look after a seemingly unconscious man on life-support who’s hooked up to some new type of cyberdrive. Slick could use the money and he owes Kid a favour, but nobody would hide in Dog Solitude without some very good reason.

That’s four fairly meaty plot-strands, and every one of them comes with a web of supporting characters, antagonists and chance encounters. It’s a densely packed book. Gibson has to progress every one of those stories, bring them ultimately together and make sense of the previous two books. He pulls it off in just over 300 pages. Neal Stephenson and David Mitchell could take a lesson here.

In Neuromancer and Count Zero Gibson focused largely on characters who were outsiders – professional criminals, small-time chancers and has-beens hoping for a comeback. What they had in common was that whether they knew it or not they were largely caught up in other people’s schemes. They were protagonists, but they weren’t the ones actually driving the story.

He largely continues with that approach here, though with some modifications. Angie is the first viewpoint character who’s already at the top, not trying to reach it (or get back to it). Kumiko is essentially a very rich schoolgirl, albeit one born into an organised crime family. Mona and Slick also depart a little from the Gibson mold to date, with neither of them having any significantly greater ambition than not to be drawn into the book’s plot.

Put simply, over the course of the trilogy you can see Gibson expanding his range. Where in Neuromancer everyone is essentially a player, by Count Zero we have everything from international stars to cheap hookers. It’s a much more varied character palette. I don’t want however to oversell this point. Gibson has a greater range of characters, but none of them are particularly deep or nuanced. There simply isn’t space. Gibson is a writer of impressions, not details.

One problem with writing a review over a month after reading the book is that while it’s easy to remember plot and character it’s much harder to remember subtler elements such as themes. To an extent though that perhaps also reflects the fact that Mona Lisa is less interested in exploring issues of dehumanisation and how the rich and poor may as well be different species than it is in bringing the trilogy to a satisfactory conclusion. Gibson is still writing about the intersection of money and the street, but that’s a continuation of an overarching theme rather than the introduction of anything new (and arguably a strand running through his broader body of work).

Mona Lisa then is a novel for the existing fan. That doesn’t make it bad – I happen to think it’s very good – but it assumes you’ve already bought into Gibson’s world. It’s a wrapping up, not an opening out.

Gibson remains a brilliant conjurer of the detritus of modern industrial society. The title of this piece comes from the middle of a descriptive passage and seemed to me a quintessentially Gibsonian line. Similarly, this quote for me couldn’t come from any other writer:

Slick spent the night on a piece of gnawed gray foam under a workbench on Factory’s ground floor, wrapped in a noisy sheet of bubble-packing that stank of free monomers.

It’s not a Gibson novel if nobody’s sleeping on foam. It’s a sentence however which is classically Gibsonian not just in having a foam bed, but more to the point in its evocation of a whole world from an imagistic handful of details. It’s easy to see what Gibson’s describing, but more than that you can also feel it, hear it and smell it. Gibson is able to pack a tremendous amount of sensory noise into a very small space.

That, perhaps, is why his futures convince even though the details are nonsense. It’s because they feel lived in, and because they feel messy and full of people making do the best they can to get by. Here newspapers are distributed by fax which leads to huge piles of discarded fax paper, which is used by the poor as free insulation or bedding. It’s in one sense an incredibly dated idea. Here in 2015 writing this I can’t recall when I last saw a fax. It feels real though, because it fits with the world we do know. I travel to work on a tube train filled with discarded free newspapers which get collected up by the homeless to line their sleeping bags. The details are different, but the imagined future is still surprisingly prescient because it was really a mirror of the present.

Interestingly, where the book dates most isn’t the bizarre ideas of how computers work or the omnipresent fax paper but the descriptions of London and the Portobello Road. I grew up within a short walk of Portobello, and it’s oddly nostalgic to see Kumiko visiting markets I remember from childhood that have long since been priced out of what is now one of the most expensive parts of London.

Gibson didn’t predict the gentrification of the Ladbroke Grove area, which is fair enough because he’s not in the prediction business. He wouldn’t have been surprised by it though, because if there’s one thing Gibson does understand it’s what it feels like to have your face pressed up against the glass with people who have everything just on the other side and never giving you a single thought.

She remembered Cleveland, ordinary kind of day before it was time to get working, sitting up in Lanette’s, looking at a magazine. Found this picture of Angie laughing in a restaurant with some other people, everybody pretty but beyond that it was like they had this glow, not really in the photograph but it was there anyway, something you could feel. Look, she said to Lanette, showing her the picture, they got this glow.

It’s called money, Lanette said.

The Sprawl trilogy remains one of my favorite trilogies in fiction. As a whole, it’s a landmark piece of SF and it’s no surprise to me at all that it remains readily in print. This was perhaps my third rereading over the years, and I can’t rule out there won’t be more. Gibson’s future remains relevant because we are part of it, because we always were part of it. SF futures are often a refracted present, but rarely so much so as here.

Other reviews

None I’m aware of from any of the blogs I regularly follow, but please feel free to link me to some in the comments if you know of any particularly interesting ones.

Filed under: Gibson, William, Science Fiction Tagged: Sprawl trilogy, William Gibson