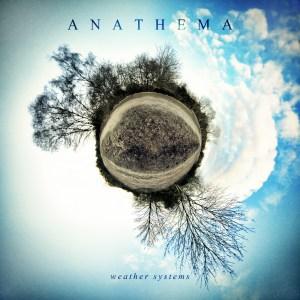

Even the cover is great!

Over time, as you write a blog site and review a lot of albums, it becomes clear what your favorite topics are, whether you chose ’em or they chose you. For instance, my favorite band for most of my life was/is The Church; hence, there’s a lot of content on this site about that band. I’ve had a long time to listen to and absorb their music, so my thoughts have some currency. Another, more recent phenomenon in my listening life is Liverpudlian band Anathema, of which you will find a summary here. It’s been a couple of years since I “discovered” the band’s music, and now I must say, when I need a pick-me-up, out of the literally thousands of albums I possess, theirs are very often the ones I reach for. And this one in particular. That’s why there is an embarrassingly large amount of Anathema-related content to be found here.

For each passionate listener of music, there are a lot of albums you really enjoy, but then there’s another rarified category, those perfect jewels that require you to take an hour to sit back with the headphones on, close your eyes and let them work their mood-altering magic on you. Albums so perfect that you just can’t figure out why not everyone hears in them the same transcendent beauty that you do. Well, that’s the glory of individuality, of course. I’ve written a few posts on such albums for me (see The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway and The Pearl). Anyway, sure, I’ve expended a lot of textual effort on Anathema, and that’s probably enough, but that work felt unfinished without a more in-depth discussion of this masterpiece. When you find yourself called to write about something, you might as well do it.

Long story short, Anathema has always thought big: big sound (though often subtle, but in a big way), big ideas, big emotions. While I’ve been coming to a greater appreciation of the band’s earlier work in the doom rock arena, I still maintain that they hit their stride with 2010’s We’re Here Because We’re Here, which broadened the sonic palette but also the emotional one with songs like the soaring ballad “Dreaming Life” and joyously life-affirming “Everything”. There’s plenty of melancholy on there as well, but a philosophical maturity and a new ability to express profound thoughts in a simpler, more direct fashion, and even happiness when appropriate.

And after this particular album, 2014’s Distant Satellites represents a step in different, more electronic directions. It’s also a lovely album that listen to frequently. However, as “rock” band, Weather Systems really does represent the apex of Anathema’s career, as well as probably the apex of modern “progressive” or “art” rock. Can they do the same or better in the future? Why not! But in the meantime, throw away your Radioheads and Coldplays, put Steven Wilson aside for a moment, consign Muse to the back of the cupboard. Without artifice but with consummate artistry, Anathema, which is led by the Cavanaghs, Daniel and Vincent (assisted by yet another Cavanagh on bass), songwriting drummer John Douglas and celestial-toned vocalist Lee Douglas, send the open-hearted listener on a sonic and emotional journey like no other.

This is not a “concept” album as far as I can tell, in that there’s not a story arc per se, or a story, but definitely there is a theme, as expressed through the weather motif. Mortality and grieving have been songwriting interests of the Cavanaghs for their entire career; this probably explains my affinity for their work, since I’m pretty well exactly the same in my own. Not all the songs on this album appear to be on that subject, but many are, not only in a philosophical sense, but in tracing the emotional journey of a grieving soul.

Musically, the album is grand without bombast; strings arranged by former National Health member Dave Stewart add poignancy, but not pomp. Ebow guitars soar with the strings, while folk acoustics underpin everything. Glorious harmony vocals glide as the arrangements ebb and flow.

Right off the bat, my brain registered something special when I heard the opening finger-picking of “Untouchable Part 1“. Starting at a slow burn, Vincent Cavanagh’s carefully controlled vocal intones simple words of loss before the band explodes into a rage, and his voice jumps a register. Stentorian and unyielding, he declares his love for his lost one without regret or recrimination. A cry to love, indeed!

Cleverly, the band then inverts the song, taking elements from it to craft the resigned counterpoint, “Untouchable Part 2″, in which Lee Douglas finally gets a starring role in the band’s music she always did, dueting to devastating effect with Vincent. The tone of this song is more resigned, with defiance replaced by an understanding of loss and a coming to terms with it. Still, a crescendo of shoegaze guitar and strings tells us that that the passion burns behind this stoicism.

These are basically two perfect pieces of music.

However, the rest of the album’s no slouch. Continuing with the meterological motif, “The Gathering of the Clouds” is basically one big build-up, starting tense and getting tenser and loud, but it’s no throwaway; the carefully arranged vocals contain many clues to the album’s theme: “The life we live is like a dream”, ” Time is not what it would seem”, “Let love reveal what I feel”. These aren’t the words of some complex poet, and coming from the pen of lesser musical talents they’d have little meaning. Somehow, Cavanagh manages to take simple thoughts and words and couch them in just such a way that their true meaning is emphasized.

The final boom this song suddenly subsides into the delicate broken chords of “Lightning Song“, another great folk-based touch. This is the track that establishes Lee Douglas as a great talent, a showcase of sustained notes and controlled beauty that matches the simple elegance of the lyrics. Again, Douglas appears to address a deceased loved one, not just an ex, and she declares her desire for peace of mind, then finds it: “This world is wonderful, so beautiful/If only you can open up your mind and see/Your world is everything you ever dreamed of/If only you can open up your mind and see.” And then the band brings it home with crashing power chords and sky-high strings and mind-blowing drum fills.

Already we have more great songs here than most bands record in a lifetime. Daniel Cavanagh’s personal and intimate showcase, “Sunlight”, is a quite, well, sunny ballad, melancholy but beautiful in its purity: “Say you will love me until I leave the world”.

John Douglas only wrote one track here, but it’s a doozy. “The Storm Before the Calm” starts with several minutes of tense group vocal verses mixed with electronic buzzing. After a cacophonous interlude of avant-garde noise, slowly, sparse guitar and piano usher in an elegant Floydian track on which Vincent just wails vocally — one of his finest performances. And there are a few interesting chord changes to keep things interesting. A really great piece of classic progressive rock sure to please any progger.

The album’s two “deeper” tracks that require some focused attention are wisely placed toward the end, “The Beginning and the End” being highly dramatic and slightly more precious lyrically speaking than the rest of the album, hearkening back to the band’s doom metal days. Still, it’s hard to resist the deathly seriousness and bleak poetry of lyrics like: “Inside this cold heart is a dream/That’s locked in a box that I keep/Buried a hundred miles deep/Deep in my soul in a place that’s surrounded by aeons of silence.” And the album’s one and only bona fide guitar solo is here too, a series of beautifully sustained bent notes.

“The Lost Child” really highlights the Debussy-esque nature of Stewart’s arrangements, reminding me very much of the arrangements on old Brit-folk albums by Sandy Denny and Nick Drake. While this song also leads inevitably to a big crescendo, it’s during the quieter parts, in which Vincent Cavanagh showcases his ability to sing with childlike delicacy, matched with the reverby piano, that the track really shines.

Finally, the album reaches the all-important closer. Regular readers know of my obsession with having a great album closer; without it you have failed in your mission. And an album of this ambition requires a true monster of a closer. Well, it has it in “Internal Landscapes“! Daniel Cavanagh took the audio of an interview from the seventies with near-death survivor Joseph Geraci describing his “last” moments on Earth and put it over ambient music. Geraci’s warm, authoritative retelling of his experience leads into a song that builds up (of course!) into a grand finale of churning guitars and soaring vocal notes — as well as lyrics of profound hope that reject the sorrow of death and look toward an absorption in the greater reality, the shining sea: “For I was always there/And I will always be there…” Geraci’s final thoughts conclude the song, and the album.

As a personal postscript, when I was putting together my own modest recording on the subject of mourning, I wrote original music but wanted to accompany it with some of my favorite songs by others on this subject. And it says a lot that out of a list of about twenty songs I had selected, of the three that made the cut, “Internal Landscapes” was one of them. If you want to hear my ambient folk rearrangement, here it is.

Weather Systems is an album I return to again and again, as if compelled. I can think of few other pieces of art I’ve come across that have had such an effect on me. While it might not have that effect on you, if you have a penchant for serious music that ponders greater realities and sincere emotions, I cannot see how you’d fail to enjoy this album, which may well be career-defining for its creators.