originally published in Brave Minds, Flinders University’s research-news publication (text by David Sly)

Clues to understanding human interactions with global ecosystems already exist. The challenge is to read them more accurately so we can design the best path forward for a world beset by species extinctions and the repercussions of global warming.

This is the puzzle being solved by Professor Corey Bradshaw, head of the Global Ecology Lab at Flinders University. By developing complex computer modelling and steering a vast international cohort of collaborators, he is developing research that can influence environmental policy — from reconstructing the past to revealing insights of the future.

As an ecologist, he aims both to reconstruct and project how ecosystems adapt, how they are maintained, and how they change. Human intervention is pivotal to this understanding, so Professor Bradshaw casts his gaze back to when humans first entered a landscape – and this has helped construct an entirely fresh view of how Aboriginal people first came to Australia, up to 75,000 years ago.

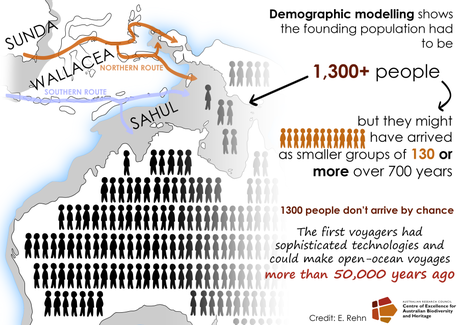

Two recent papers he co-authored — ‘Stochastic models support rapid peopling of Late Pleistocene Sahul‘, published in Nature Communications, and ‘Landscape rules predict optimal super-highways for the first peopling of Sahul‘ published in Nature Human Behaviour — showed where, how and when Indigenous Australians first settled in Sahul, which is the combined mega-continent that joined Australia with New Guinea in the Pleistocene era, when sea levels were lower than today.

Professor Bradshaw and colleagues identified and tested more than 125 billion possible pathways using rigorous computational analysis in the largest movement-simulation project ever attempted, with the pathways compared to the oldest known archaeological sites as a means of distinguishing the most likely routes.

The study revealed that the first Indigenous people not only survived but thrived in harsh environments, providing further evidence of the capacity and resilience of the ancestors of Indigenous people, and suggests large, well-organised groups were able to navigate tough terrain.

“Humans are highly adaptable and show a huge capability to change. Tracking the movement of the first Aboriginal people in Australia proves they were adept, able to enter a completely foreign landscape and to make their new communities thrive,” says Professor Bradshaw. “Understanding this not only challenges a colonial and racist view of Aboriginal culture, it also underlines the great cognitive powers humans have always shown to solve problems and to progress.”

Beyond using data to reconstruct pictures of the past, Professor Bradshaw’s analysis can also assess possible future scenarios, investigating how environmental modification will comprise human health, wealth and wellbeing.

The most effective summary has been a chilling perspective paper — ‘Underestimating the challenges of avoiding a ghastly future‘, published in Frontiers in Conservation Science — in which the team of scientists led by Professor Bradshaw say continuing loss of biodiversity and accelerating climate change in the coming decades coupled with ignorance and inaction is threatening the survival of all species.

The paper cites more than 150 studies, outlining likely future trends in biodiversity decline, mass extinction, climate disruption, and planetary toxification that are all tied to human consumption and population growth. The modelling demonstrates that these problems will worsen over coming decades, generating negative impacts for centuries to come.

“We are underestimating the number of extinctions on our planet by at least half the real number, and we are becoming less, not more, able to tackle these problems,” says Professor Bradshaw.

The paper explains the impact of political impotence and the ineffectiveness of current and planned actions to address the ominous scale of environmental erosion.

It rang loud alarm bells, was picked up by international media and triggered a global call for political leaders to take more decisive environmental action.

“I’m not looking to the past to predict the future. I think that’s a very weak premise for future predictions. But through accurately analysing the past, we can make a strong argument for constructive change,” says Professor Bradshaw.

“In the case of bushfires, for example, there are lots of existing factors that can provide probabilities of occurrence, extent and intensity — and that’s a valuable guide that we need to pay attention to.”

Professor Bradshaw’s work relies on sophisticated computer modelling that he has developed, and enables such research by being versatile enough to look both backward and forward with powerful predictive capacity.

Using this tool, his research follows paths not usually trodden by ecologists, as he examines the functional links and implications of environmental integrity affecting human health, climate-change mitigation, low-carbon energy provision, economics, and human demography to identify long-term sustainability.

It represents different ways of thinking about measuring data and information, addressing bigger questions of how climate change affects all components of an ecosystem, including our ability to grow food in a changing environment, along with the capacity to cope with natural disasters.

Progressive modelling also enables more complex interdisciplinary collaborations that produce expansive, interconnected research. In the follow-up to the influential “ghastly future” paper, Professor Bradshaw has engaged the expertise of 62 authors from across the sciences and humanities, plugging him into the center of a crucial global conversation.

It provides a taste of what other diverse collaborations are possible and shows that the outcomes of such studies can have powerful influence on policy decisions. “Presenting evidence is critical for sound decision making,” says Professor Bradshaw. “Humans tend to decide emotionally before acting rationally. Sound research points to the reason why things occur. Policies can influence how outcomes occur, so this is a policy-influencing method of research.”

Professor Bradshaw is confident that more detailed examination of the interconnectivity of species and natural events affecting them, such as fires and floods, will reveal ever more complex cascading relationships. The more scientists can draw into these research conversations, the better the outcomes – and even in an era of stalled travel, global research collaborations are flourishing thanks to the rise of online meeting and discussion platforms that facilitate easy international communication.

“By being so expansive and international with our research, we are all speaking in a common language. I consider this a great privilege to be steering this work from Flinders University,” says Professor Bradshaw. “We need all these experts involved, because only by working together can we turn commonly held environmental truisms into numbers and data that can lead us towards solutions.”