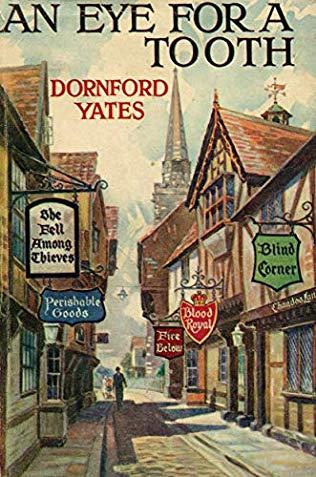

Book review by George S: This is one of Dornford Yates’s Chandos series of thrillers. The cover of the first edition makes that very clear. It pictures a mediaeval-looking street (which does not correspond to any location in the novel) hung with signs advertising the previous thrillers in the series. It’s an odd cover – but presumably drove home the message that Yates was in this book providing the mixture as before.

If you don’t know Yates, here’s a brief run-down of his rather odd writing career. In the teens and twenties he specialised in the ‘Berry’ series – short stories about a group of upper-class friends. Light-hearted and snobbish stories, often showing the heroes getting the better of someone nouveau riche, or foreign, or Jewish.

By 1927 Yates was running out of steam with this kind of book, so took one of the cast of the comic series – Jonah Mansel – and made him the lead of a thriller, Blind Corner (1927).

This is very much an imitation of John Buchan, and of Sapper’s ‘Bulldog Drummond’ series. Buchan, Sapper and Yates have sometimes been classed together as the creators of ‘Clubland Heroes’ (and sometimes as purveyors of ‘Snobbery with Violence’).

The essence of Bulldog Drummond was that he was an ex-soldier bored with civilian life, who uses the skills learned in war to combat peacetime villains – criminals, foreigners, socialists, etc. In 1927, Yates came rather late to the game. These were action novels, and ex-soldiers were now getting on a bit. So while he has ex-soldier Jonah Mansel as his main hero, he has him recruit two of the younger generation to help him – Richard Chandos and George Hanbury, who ‘had lately been sent down from Oxford for using some avowed communists as many thought they deserved’. This would have struck a chord in 1927, just after the General Strike, when Oxford and Cambridge undergraduates were much praised for their efforts in strike-breaking. Chandos and Hanbury were the sort of young man who showed older readers that there was hope for England yet.

The novels are sometimes called the ‘Chandos’ series because Richard Chandos is the narrator.This novel is set in Austria. Mansel, Chandos and Hanbury are on their way back from the events described in Blind Corner, driving through Austria, when they come across a dead body in the road. They spot clues that the man has been murdered and – more intriguingly – that someone seems very anxious for the body to be found. They decide to hide the body and see what happens.

Soon they are in the middle of an evil plot. The corpse was an Englishman, Major Bowshot. He will turn out to have been a decent man in love with the wife of an evil Austrian duke, who arranged his murder with the assistance of some scheming English solicitors who had their own reasons for wanting him dead.

The book is a straight conflict of good and evil. The three heroes are dauntless, upright and Brave. The Duke is demented, and the men he employs to carry out his dirty work are all evil and repulsive. Here is a description of one of them:

Biretta was truly repulsive. He was short and fat and greasy and overdressed. His skin was very swarthy, his hair was black and he had a way of pursing his heavy lips. His face was fleshy, his eyes were small and close-set, and his air was very pompous, as is the way of small fry when an unfamiliar greatness is thrust upon them.

The bad men are not only repulsive but stupid and inefficient. Mansel knows this and turns it to his advantage:

Indeed, he always maintained that rogues, as a whole, were a very lazy lot, so that, if, when you stood against them, yourself you took infinite trouble and infinite care, the odds would be in your favour time and again.

What is more, they are forever at odds with one another, quarreling among themselves, turning traitor, and doing anything to save their own hides. This is in contrast with the British trio, always loyal, utterly dependable, and utterly obedient to Mansel’s commands. The characters in these books I can’t help being fascinated by are the three servants who accompany Mansel, Chandos and Hanbury. These have absolutely no characteristics except loyalty and obedience. They accompany their masters on the adventures, never offer an opinion, risk their lives and endure tedious jobs like keeping watch without complaint. They are the English middle-class idea of what the working-class should should be like in a perfect world.

The evil duke goes in for vile punishments. To trap the heroes he sets huge man-traps with three-foot high jaws, set to grab intruders just above the waist and condemn them to an agonising, lingering death. He also has a hunting-lodge with a booby-trapped floor that suddenly gives way to land victims in the charnel-house below. Yates has a great zest for describing horrible cruelties, which of course justify the violence of his heroes, who murder just about all of the criminals and their associates in the course of the story, but never doubt that they have the moral high ground. The appeal of Bulldog Drummond was that he took readers away from the complexities of the twenties to the a black-and-white morality where enemies were as obvious as they had been on the battlefield.

Yates is like Sapper, but exaggerated. The evil is worse, the decency of the heroes is even greater. Mansel is never as down-to-earth as Bulldog Drummond. You could describe Yates’s thrillers as a high-camp version of Sapper’s.

One odd thing – this 1943 novel goes back to tell of events that had happened immediately after Blind Corner of 1927 (even though several other Chandos/Mansel novels had appeared in the meantime. Does this indicate that Yates was unsure of what do do with his heroes in wartime, so took them back to familiar territory? Perhaps he sensed that this would be popular with readers?

The book is full of the standard prejudices: of one of the evil gang Mansel says:

I’ve seen his type before. He’s German inside and out. But he is a moral coward, as every German is.

Mansel predicts that this cowardice will make the man behave in a certain way – and indeed it does.

So – the book is formulaic, prejudiced and cliched, but on the other hand it has great narrative zest. When those giant man-traps were set, I really wanted to know who would be caught in one of them (Spoiler alert – it’s the evil Duke). So- final verdict on the book: appallingly readable.