Extinction is forever, right? Yes, it’s true that once the last individual of a species dies (apart from insane notions that de-extinction will do anything to resurrect a species in perpetuity), the species is extinct. However, the answer can also be ‘no’ when you are limited by poor sampling. In other words, when you think something went extinct when in reality you just missed it.

Extinction is forever, right? Yes, it’s true that once the last individual of a species dies (apart from insane notions that de-extinction will do anything to resurrect a species in perpetuity), the species is extinct. However, the answer can also be ‘no’ when you are limited by poor sampling. In other words, when you think something went extinct when in reality you just missed it.

Most of you are familiar with the concept of Lazarus1 species – when we’ve thought of something long extinct that suddenly gets re-discovered by a wandering naturalist or a wayward fisher. In paleontological (and modern conservation biological) terms, the problem is formally described as the ‘Signor-Lipps’ effect, named2 after two American palaeontologists, Phil Signor3 and Jere Lipps. It’s a fairly simple concept, but it’s unfortunately ignored in most palaeontological, and to a lesser extent, conservation studies.

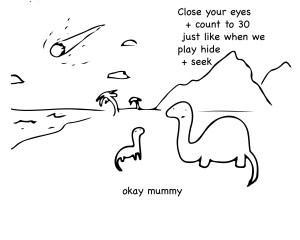

The Signor-Lipps effect arises because the last (or first) evidence (fossil or sighting) of a species presence has a nearly zero chance of heralding its actual timing of extinction (or appearance). In paleontological terms, it’s easy to see why. Fossilisation is in fact a nearly impossible phenomenon – all the right conditions have to be in place for a once-living biological organism to be fossilised: it either has to be buried quickly, in a place where nothing can decompose it (usually, an anoxic environment), and then turned to rock by the process of mineral replacement. It then has to resist transformation by not undergoing metamorphosis (e.g., vulcanism, extensive crushing, etc.). For more recent specimens, preservation can occur without the mineralisation process itself (e.g., bones or flesh in an anoxic bog). Then the bloody things have to be found by a diligent geologist or palaeontologist! In other words, the chances that any one organism is preserved as a fossil after it dies are extremely small. In more modern terms, individuals can go undetected if they are extremely rare or remote, such that sighting records alone are usually insufficient to establish the true timing of extinction. The dodo is a great example of this problem. Remember too that all this works in reverse – the first fossil or observation is very much unlikely to be the first time that the species was there.

So you can probably appreciate that fossil time series, say, in layers of rock, accurately attest the full chronology of a species through geological time. Digging through layers of rock and finding the first incidence of a fossilised individual of species X (i.e., the youngest) down to the last (i.e., oldest) therefore cannot be taken as the species’ lifespan on Earth.

Fortunately, some statistical models exist to counter this problem, and they are invariably based on some assumptions regarding the temporal patterns of the fossil dates within the time series. I’ve written before about some of my own work in this area, and my postdoc, Dr Fréd Saltré, has recently improved on that and extended the analytical framework.

Now, I don’t care if you are working on Ediacaran assemblages, examining the Cretaceous-Palaeocene mass extinction event, or trying to establish the appearance/extinction chronology of a modern nematode – if you do not account for the Signor-Lipps effect, you cannot presume to present the true nature of the species’ (or population’s) chronology. So why is it then that so few people attempt to account for fossilisation (observation) bias? Yes, there are probably more incidences than not where you simply cannot apply a particular time series to the extant models designed to tackle the problem, such as when there are too few dated fossils (e.g., < 5-10). But if you had three fossil dates of species X and then tried to tell me that it speciated at the date of the first fossil and then went extinct at the date of the last, I would tell you that you’re full of shit, and that your evolutionary inference is fundamentally flawed.

Much of our understanding of evolution is predicated on palaeontological time series that have not been treated properly, so it stands to reason that there will be many chronological revolutions over the coming decades. Let’s stop being so dyscalculic when it comes to extinction!

CJA Bradshaw

1A most unfortunate term because its source is a religious myth.

2Peter Ward told me once that he was responsible for naming the effect, but was usurped. I don’t know the full details

3He resigned from his post under dubious circumstances.