"Life's too short to be pissed off all the time."

It seems timely to revisit American History X (1998) this weekend, a sad commentary on the state of America in 2017. Tony Kaye's scintillating portrait of hate was edited against his wishes by the studio and star Edward Norton, yet the end result remains extraordinarily powerful.Derek Vinyard (Edward Norton) emerges from prison, having served three years for killing two black men attempting to steal his car. A former Skinhead, Derek's determined to go straight, but that's easier said than done. His old boss Cameron Alexander (Stacy Keach) and girlfriend (Fairuza Balk) are eager to absorb him back into their lifestyle, while his brother Danny (Edward Furlong) seems determined to follow his brother's lead. Derek tries to make amends for his past actions despite considerable risk to himself and his family.

Kaye invests American History X with the sweep and power of a classical tragedy, invoked with slow motion photographic tricks, monochrome flashbacks and Anne Dudley's lushly melodramatic score. David McKenna's script adopts an anachronic order, filling in key bits of back story and character development as the story requires. This device (along with the framing story of Derek and Danny reconnecting) works better than expected, as it evades easy answers even for personal racism.

Certainly Derek's descent into bigotry follows a pat, almost Freudian structure at first: he's traumatized by his policeman father's death, easily targeted by pseudo-intellectual Cameron, eager at the identity and power his new identity gives him. He falls in with easy friends and adopts a swagger and charisma he lacked before, standing up to his ineffectual mom (Beverly D'Angelo) and teacher (Elliot Gould). Even so, his creed's rooted in violence and exclusion, and no amount of rhetorical posturing about saving America can overcome it. When he stomps a robber to death with his feet, it's merely the logical culmination of spiraling hatred.

Kaye and McKenna don't make grandly sweeping statements about race and hatred, allowing the characters to do their own talking. Even so, it's unnerving to see how easily Derek lapses from standard conservative talking points on crime and immigration to open slurs and death threats. Suggesting Rodney King deserved a beating only differs from his rants about the Jewish media or pomelling Asian shopkeepers by a matter of degrees. It's even more chilling, two decades later, to see Alexander muse on how the Internet will allow racists everywhere to share ideas and coalesce into a powerful force. Anyone desiring to hand wave hatred as "economic anxiety" should realize that, in effect, it's a distinction without a difference.

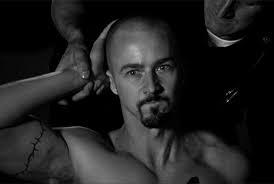

Edward Norton gives the performance of his career. Initially presented as a cocky, swaggering embodiment of bigotry, he slowly mellows into a more conflicted character, forced to consider the consequences of his actions and ideology long after they've landed. Edward Furlong fares adequately as Danny, though he's mostly given reaction shots and callow whining to deal with. Fairuza Balk's creepy-erotic gal pal and Ethan Suplee's loudmouthed redneck provide disturbing anchors into racist subculture. Stacy Keach's mellow, cunning white supremacist is a master class in understated evil.

The worst one can say about American History X is that its classical structure allows for few dramatic surprises, not least with an preordained from the first frames. One also finds Avery Brooks' understanding principal, a conduit between the brothers and liberal rationalism, more of a preachy plot device than character. These seem only minor shortcomings considering how powerful, striking and depressingly relevant this movie remains.