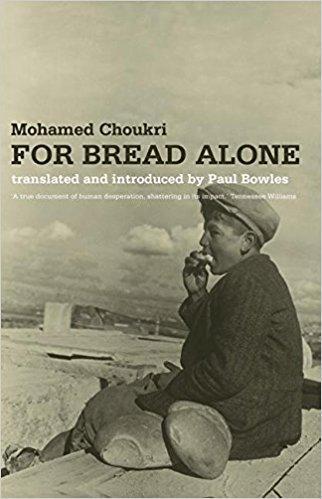

For Bread Alone, by Mohamed Choukri and translated by Paul Bowles

Mohamed Choukri is an interesting figure. He came from a desperately poor background and didn’t learn to read until his early 20s. He wrote a famous autobiographical trilogy of which For Bread Alone is the first. It covers those early years up until he decided to become literate and is utterly unflinching in its depiction of the experience of abject poverty.

Normally that’s not the sort of thing I’d read. I detest misery memoirs and bildungsroman is one of my least favorite genres. I made an exception here partly as I’ve heard this is an influence on Mathias Enard’s Street of Thieves, partly as Stu gave it a good review on his Winston’s Dad blog and partly as I was intrigued to see what had caught Paul Bowles’ attention so strongly that he chose to translate it.

In this piece I’m going to refer to Mohamed when I’m referring to Choukri as character within the book and to Choukri when I’m referring to him as author.

For Bread Alone opens with Mohamed and his family moving from their native Rif region of Morocco to Tangier. Rif has its own language and ethnic identity and Mohamed’s accent will immediately mark him out in Tangier as an outsider. They’re making the journey from desperation – the Rif has had no rain and that means no food:

We were making our way towards Tangier on foot. All along the road there were dead donkeys and cows and horses. The dogs and crows were pulling them apart. The entrails were soaked in blood and pus, and worms crawled out of them. At night when we were tired we set up our tent. Then we listened to the jackals baying.

When someone died along the road, his family buried the body there in the place where he had died.

Mohamed’s uncle has just died so the family is reduced to him, his younger brother Abdelqader who is too sick during the journey even to cry, his mother and his violent father. When they reach Tangier it’s no promised land: food remains so scarce that Mohamed even tries to scavenge a dead chicken from the street despite its being evidently carrion.

Mohamed’s father struggles to find work. Each day he comes home disappointed and savagely beats anyone within reach in revenge for his frustrations. Within the first few pages of the book he grows angry at Abdelqader’s constant crying from illness and hunger and in a fit of rage kills him. It’s a crime for which he will never be punished. It’s little surprise that Mohamed grows up wild.

For Bread Alone is utterly unsparing not just of those around Mohamed but of his failings also. For a while he’s sent to stay with relatives in the country and things seem to be looking up for him, until he sexually assaults a younger boy (he’s not gay in any contemporary sense of that word, there just aren’t any women to hand). The pointless ugliness of this next incident for me shows his father’s influence:

One day I tried in vain to climb a high tree. That leg was tall and smooth. I grew very angry at being repulsed, and so I went to the shed and filled a can with gasoline. I doused the tree trunk and lit a match. The flames were beautiful. I said to the charred tree: Now you’re not so smooth. I can climb you, as high as I want.

As he grows older his acts of pointless aggression tail off somewhat, but he remains a hustler. He sells himself, steals, becomes a vicious brawler and spends the little money he gets on drugs and prostitutes. He’s obsessed with sex, in one dry period carving a tree to look vaguely like a woman and then having sex with that. (He uses lubricant you’ll, perhaps, be glad to know).

So why read this? With this much ugliness, violence and squalor why read any of it? Well, for the absolute honesty but also for the empathy. Choukri doesn’t pretend he had some special claim on suffering or that others weren’t doing equally badly. He doesn’t pretend to have been a victim. He takes the reader into the lives of people lost in drugs, hustling and violence as did say Burroughs and Bukowski but where they just show what is Choukri also explores the why. He shows the lack of better opportunities and why living as these people do may very well be a rational decision given their circumstances.

At times this is reminiscent of Knut Hamsun’s Hunger, particularly earlier on in the book before Mohamed becomes an established hustler.

Now I chew on the emptiness in my mouth. I chew and chew. My insides are growling and bubbling. Growling and bubbling. I feel dizzy. Yellow water came up and filled my mouth and nostrils. I breathed deeply, deeply, and my head felt a little clearer. Sweat ran down my face.

At other times it becomes existential. What sets Mohamed apart from those around him is his intelligence and the potential it brings, but for most of this book he’s yet to realize either. Even so, as he reaches his twenties he becomes more than merely reactive and starts to think about who he is and how he fits into the world.

I thought the meaning of life was in living it. I know the flavor of this cigarette because I’m smoking it, and it is the same with everything.

The test for any book which is part of a trilogy is whether or not you’d read the others. On balance, I would read more by Choukri. It’s admittedly a fairly fine balance as while this is well written I’m not generally interested in memoirs nor in exploring others’ poverty, but Choukri’s empathy and intelligence make this worthwhile. Unfortunately, while a Bowles translation is available for this volume there don’t seem to be equivalent translations for the others and I’ve seen what is available criticised for omissions and unnecessary changes. That means that sadly this is probably where my exploration of Choukri stops.

One last word: For Bread Alone comes at the beginning with a handy glossary of words that Bowles chose not to translate, presumably either for lack of a direct equivalent or for the color they gave the text. One of these read as follows:

zigdoun: a woman’s garment, akin to a Mother Hubbard

Thanks Paul. Unfortunately I then had to google a Mother Hubbard. Funny how references can age.

Other reviews

The only one I know of among the usual suspects is the one that helped spark my interest in this, which is Stu’s here from his Winston’s Dad’s blog.

Filed under: Arabic Literature, Choukri, Mohamed, Memoirs Tagged: Mohamed Choukri