[Cross-posted to By Common Consent]

[Cross-posted to By Common Consent]My father decided that we needed to learn how to work--and since he ran a feed mill, getting farm animals that we could feed relatively cheap seemed like the best idea. My father had been part of the world of alfalfa fields and cattle auctions since he was a child, but he wasn't a farmer, per se; just someone who knew and respected the social and economic place of farm life, and saw an opportunity to continue to make it a part of his children's lives. As so we got dairy cows, and starting around age nine, I and my older brother Daniel and older sister Samatha would milk them (usually two, sometimes three, sometimes only one) by hand, morning and night. Of course, that would include Christmas.

I'm a fan of holidays and traditions; I always have been, and probably always will. As a child, as a believer in Santa Claus (my father, I recall, informed Samatha and Daniel and I all together when I was seven or eight that there was no Santa Claus, and I insisted he was wrong, a position which I continue--with perhaps a little more philosophical sophistication--to maintain to this very day), I would attempt to talk to the cows on Christmas eve and Christmas day, in the hopes that they would speak to me, as the legend says they can on Christmas. But of course, they never did--not with words, anyway. And of course they wouldn't; they only speak at midnight, and I was always in bed by then. But I would still try.

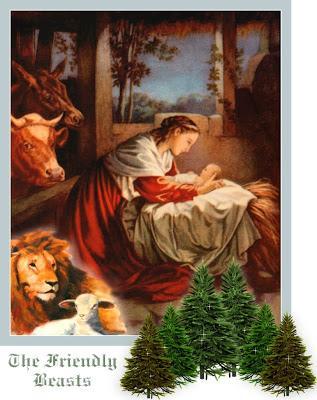

God made the cows, and all creatures great and small. I'm certain that, as part of His creation, they are, in some way imperceptible to you and I, part of the joy of this season, as they are surely part of its stillness and darkness and its surprise as well. So it is right, I think, that we imaginatively bring them into our celebration, through song and story--and through this, my favorite Christmas poem. I've linked to it before, and I read it at our congregation's Christmas celebration yesterday. I wept like an idiot as I read it, because I wished, and probably always will wish, that I could be as steady and simple as Eddi, and his audience in this poem, and the animals that I tended on Christmas eves and days decades ago:

God made the cows, and all creatures great and small. I'm certain that, as part of His creation, they are, in some way imperceptible to you and I, part of the joy of this season, as they are surely part of its stillness and darkness and its surprise as well. So it is right, I think, that we imaginatively bring them into our celebration, through song and story--and through this, my favorite Christmas poem. I've linked to it before, and I read it at our congregation's Christmas celebration yesterday. I wept like an idiot as I read it, because I wished, and probably always will wish, that I could be as steady and simple as Eddi, and his audience in this poem, and the animals that I tended on Christmas eves and days decades ago:Eddi's Service, by Rudyard Kipling

(A.D. 687)

Eddi, priest of St. Wilfrid

In his chapel at Manhood End,

Ordered a midnight service

For such as cared to attend.

But the Saxons were keeping Christmas,

And the night was stormy as well.

Nobody came to service,

Though Eddi rang the bell.

"Wicked weather for walking,"

Said Eddi of Manhood End.

"But I must go on with the service

For such as care to attend."

The altar-lamps were lighted --

An old marsh-donkey came,

Bold as a guest invited,

And stared at the guttering flame.

The storm beat on at the windows,

The water splashed on the floor,

And a wet, yoke-weary bullock

Pushed in through the open door.

"How do I know what is greatest,

How do I know what is least?

That is My Father's business,"

Said Eddi, Wilfrid's priest.

"But -- three are gathered together --

Listen to me and attend.

I bring good news, my brethren!"

Said Eddi of Manhood End.

And he told the Ox of a Manger

And a Stall in Bethlehem,

And he spoke to the Ass of a Rider,

That rode to Jerusalem.

They steamed and dripped in the chancel,

They listened and never stirred,

While, just as though they were Bishops,

Eddi preached them The Word.

Till the gale blew off on the marshes

And the windows showed the day,

And the Ox and the Ass together

Wheeled and clattered away.

And when the Saxons mocked him,

Said Eddi of Manhood End,

"I dare not shut His chapel

On such as care to attend."