Book Review by Chris Hopkins

Adèle and Co. is told in the first person by Boy, married to Adèle, cousin of Berry, while Jonathan Mansel is married to Daphne – they are the Count and Countess of Padua. The novel starts with the whole group on holiday in Paris apparently waking fully-clothed from an appalling debauch and with head-splitting hangovers. In fact, they have all been given drugged champagne, and Jonathan has more than a suspicion that their guest, Casca de Palk, whom they met on the train to Paris, slipped it into the bottle while cooling it. All the women’s jewelry has been removed from their persons, and equally the men’s cufflinks. But the supreme loss is the Countess of Padua’s pearls – renaissance masterpieces. Once the group’s painful heads have begun to clear, they collectively determine to track down the thief and repossess their lost pieces (they have little faith the police will do so). This leads to car-chases, disguises, eavesdropping, dangers at pistol-point, and further complications as another and violent American jewel their thief to track Casca and steal the entire hoard, while Casca tries to pass them to a sufficiently high-level US dealer/fence. All is complicated by the comic, sardonic, beer-loving, apparently lazy and highly oblique Berry, whose constant commentary confuses and perhaps amuses cast and readers (he has the reputation of being a great comic creation, but I did not find him sustainedly so). At the opening of the novel, I found it difficult at first to separate different characters and establish their relationships (the women seem rather interchangeable, as do some of the men). I also did not immediately pick up what seemed the rather in-group style of the dialog (especially that of Berry), but warmed to it after a while and picked up the excitement of following these ‘gentlemen thief-takers’, who are not above using their revolvers if they have to, but would rather use their wits on the whole. It is in the end an exciting chase full of chance, improvisation, plot and counter-plot.

Blind Corner

I think I should have read this before I read Adele & Co. – it is much more immediately approachable. It is a cracking boy’s own (or possibly just about men’s own) adventure – there is not in this book a single central female character of any note, but if this is any compensation there are plenty of car chases, an abandoned castle, improvised defences and sieges, hard physical labor against near impossible time-constraints, buried treasure, murderous baddies, a seemingly impossible escape from underground, frequent recourse to heavy-calibre revolvers and a small fellowship of ‘honourable’ gentlemen (by their own lights, though working beyond the law and leaving behind them several men shot dead in Austria). Oh dear – I was gripped despite myself. Professor Lisa Hopkins gave me this book to read, but is now a bit worried it will cause a measurable regression in the sophistication of my reading choices.

It all starts quite by chance when the first-person narrator, Richard William Chandos, a young man of twenty, is returning by car from a holiday in France to travel home via Dieppe. He and a friend, George Hanbury, have recently been sent down from Oxford ‘for using some avowed communists as many thought they deserved’ (p.1 – you see the force of my ’despite myself’ above since readers are clearly expected to sympathise with this use of undemocratic and casual political violence in recent memory of the General Strike). Chandos, having stopped to eat a picnic by the roadside, awakes from a post-lunch nap to find himself an unseen witness first to a quarrel about something called the ‘Wagensburg Treasure’, and then to the fatal stabbing of a man who refuses to share his knowledge of its whereabouts with another man called Ellis. Chandos talks to the dying man who asks him to look after his Alsatian and to look at the dog’s collar once he is safely home.

Inside the collar there is, of course, a paper about where the treasure is hidden (deep in an inaccessible secret chamber within a well), and soon Chandos has agreed with his friend Hanbury, and a new but clearly immensely capable acquaintance called Jonathan Mansel, that they will mount an expedition to recover the treasure and, if possible, to catch the murderer. As they soon find, Ellis has recruited his own band determined to get there first, and this motivates two rival missions to gain possession of the castle, to find a way of reaching the chamber and to bring the treasure home. Chandos and co. plan their mission with military precision, and the details of this, and the need to improvise numerous alterations under enemy challenge, are imagined as likely to be enthralling for the reader. Indeed, it seems a common interest in both these Dornford Yates novels for characters to compensate for the dullness of peace by pursuing opportunities to use their military skills in planning, logistics, sentry-go, weapons and in the end combat.

The story is in effect about a treasure hunt in a castle while under a state of siege, and with frequent switches in who has possession of the well and other key territories. One notable assumption is that if you hire the right kind of male servants they will naturally and loyally join in such an enterprise as part of their usual duties. Thus Carson, Bell and Rowley, all having been in the war, think nothing of acting as sentries with loaded sporting rifles and revolvers, or of working shifts through the night over a period of days to excavate a tunnel down to the secret chamber, or of swimming through freezing streams, or of being shot at, or of killing enemies when necessary and ‘justified’. Moreover, since such a character can be assumed for the right kind of servant, Yates does not have to stop to write any further characterisation for this trio! Nevertheless, the right kind of reader (and maybe even the wrong kind of reader) does want Chandos and co to win that treasure, to triumph over their numerous reverses, and to defeat Ellis and co, whose behavior throughout is as murderous and brutal as we were led to anticipate in the first chapter. I did enjoy this as a thriller and I can see why Dornford Yates became a best-seller (perhaps especially among male-readers?), but I think too many novels of this kind might not be altogether a healthy diet. Still, I think I will read the two Chandos thrillers related to Blind Corner: Blood Royal (1929) and Fire Down Below (1930). That might be enough Yates for me.

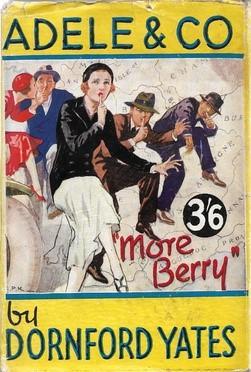

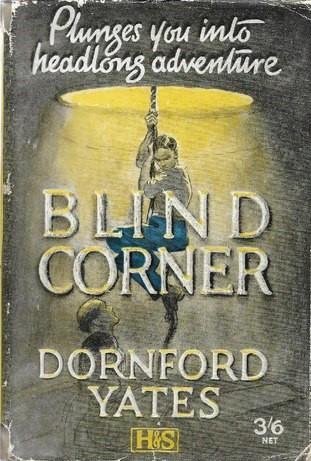

I did think that Hodder & Stoughton’s early dust-wrappers were excellently designed to match the excitements offered by each of these novels.