Active Volcanoes Located On Mars: Red Planet May Still Have Active Volcanoes

Nothing in the universe is more common than hydrogen, but here on Earth, it’s a different story. Even though hydrogen makes up nearly three-quarters of all the matter in the cosmos, it makes up less than two-tenths of a percent of the mass of Earth’s crust. But it turns out that perhaps there is more hydrogen around than scientists previously thought. It’s just not within our grasp.

In a new study published in the journal nature communications, researchers showed that there’s enough hydrogen to form 70 new oceans lurking in a pretty surprising place: our planet's core. Earth’s iron core sits around 2900 kilometers below the surface. And, although scientists cannot explore it directly, they’ve still managed to study it indirectly by analyzing patterns of seismic waves. Because seismic waves travel at different speeds through different materials.

So their speed offers clues about the type of rock they’ve passed through. And weirdly, one quirk that kept popping up in the data was that Earth’s metal core seemed lighter than models predicted. That implied that there was some lighter stuff mixed in with that iron, but what exactly that was has remained a mystery.

Also Read: Why Mount Everest is constantly changing its height

Some scientists suggested that it might be hydrogen, but that was pretty controversial, because here on the surface, hydrogen and iron just don’t bond efficiently. And although some experiments suggested they would behave differently under extreme pressure, others seemed to suggest the opposite. Still, with most of the universe being hydrogen, it’s kind of hard to rule out…

So the authors of this new study decided to try various experiments over again, under conditions much closer to those believed to exist in the core. Now, we simply do not have technology that can generate the same amount of extreme pressure that's in the core. But in this study, researchers got the closest yet.

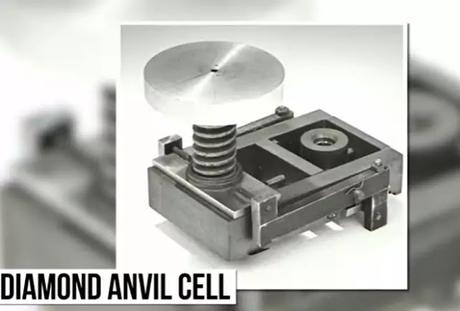

They used a device called a diamond anvil cell to crush microscopic samples till they were under a fifth as much pressure as they would experience in the core. That’s around three times better than previous work. The researchers also blasted the samples with a laser to get them as hot as 4300 degrees Celsius. And under these conditions, the team found that iron did react better with atoms of hydrogen.

In fact, their results suggest that hydrogen could account for up to 60% of the non-iron elements in the core. Now as for where that hydrogen came from? Researchers think it probably split off from molecules of water on our much younger Earth. And, if you work out just how much water would be needed to supply all that hydrogen, the answer is a lot, like, 70 times more water than is in all of the oceans on Earth today.

Also Read: Human-made objects already weigh more than all the biomass on Earth

In other recent solar system news, researchers announced the possible discovery of a previously unknown volcanic site on Mars. Which, on the one hand, is not that surprising. Mars is covered with the remnants of long-dead volcanoes. But here’s the surprising thing… this one might not be so dead.

In fact, it could have erupted as recently as 50,000 years ago. That’s the claim made in a paper published in the journal Icarus, which describes how this feature isn’t just young, but weirdly explosive compared to much of what we’ve seen on Mars.

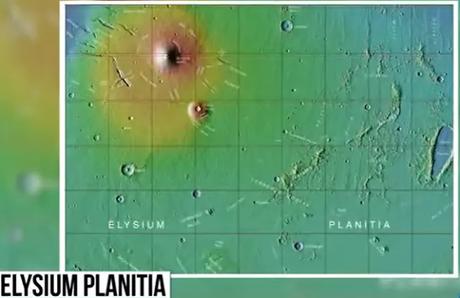

This new site is located in the region of Mars called Elysium Planitia, which is one of the most geologically exciting places on the Red Planet. Because while most Martian volcanoes erupted between three and four billion years ago, Elysium Planitia shows evidence of much more recent activity. It has some lava flows dating to around 20million years ago, and at least one that could be only a couple million years old.

The research team was analyzing high-resolution images of this region captured by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter when they noticed an almost-symmetric dark deposit only a few kilometers across. Then they looked at the same region using other instruments on MRO and NASA’s Mars Odyssey spacecraft, and what they found caught them by surprise.

In terms of both its chemistry and shape, the spot doesn’t look like much else on Mars. See, most volcanic eruptions on Mars are what's known as effusive, meaning the lava flows out of volcanoes and down its sides, all while staying on the ground. But this feature appears to be explosive, suggesting that the top of the volcano got simply blown off by an extreme buildup of pressure.

The researchers calculated that rock and ash from the explosion may have launched as high as 10 kilometers into the air before crashing back down to the ground. And by counting the number of craters on top of all that ash, they determined that this explosive event must have taken place between 50 and 200 thousand years ago. In geologic time, that’s basically now.

What’s more, NASA’s InSight lander, located around 1,600 kilometers away, recently detected two seismic events in this part of Elysium Planitia. And they may suggest that underground magma is still flowing around. And that could be a pretty big deal since volcanism is thought to have been an important factor in creating habitable conditions here on Earth. So, all things considered, this is definitely an area scientist should be keeping an eye on.