About the origins of the trollen wheel: historical or anachronistic? | #LRCrafts - DIY Passion: if you can think it, you can make it

The world of historical textile crafts is rich with fascinating tools and techniques, each with its own unique story and cultural significance. Among these, the lucet has a special place in my crafting, reenactment activities and historical researches: I even published a book on the subject. It introduced me into the real of reenactment anachronisms.

Back in 2015, at the same event where I discovered the lucet, I also stumbled upon another interesting tool, shrouded in ambiguity: a trollen wheel.

I have to say that was the only occasion I found one during a living history event. Although my focus has mostly been on the lucet, I couldn’t forget about it, though. Recently, while browsing for my lucet studies, I came across an article discussing the trollen wheel as an accepted anachronism.

Is the trollen wheel a genuine artifact from the past, or is it a modern invention born out of creative anachronism?

With a break in my lucet research, I think it’s a good time to revisit this topic and see where it leads.

Table of contents

What is a trollen wheel

First of all, what is a trollen wheel?

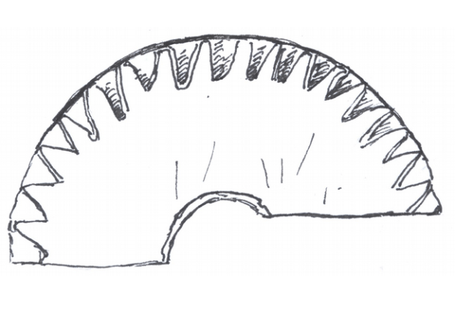

The trollen wheel, also referred to as the Trelleborg wheel, is often described as a disc with evenly spaced slots around its edge and a central hole, traditionally made from materials like bone, horn, leather, or wood. Reenactors use it to create intricate braids, similar to those produced by the Japanese kumihimo technique. However, unlike kumihimo, which boasts a well-documented history spanning centuries, the historical evidence for the trollen wheel is notably elusive.

The origin of the name is also unknown. Someone suggests that trollen is simply a corruption of the name Trelleborg. The supporters of this tool as being Viking indeed refer to a find from Trelleborg, on the Danish island of Zealand, to validate their claims.

Historical evidence and controversy

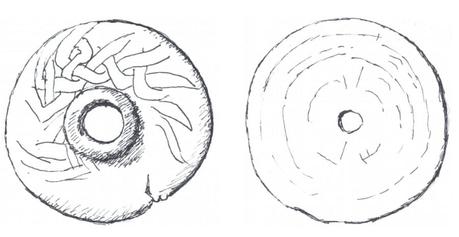

Two artifacts from Trelleborg in Denmark are frequently cited in discussions about trollen wheels. However, these items do not match the description of trollen wheels: their edges are smooth and lack the notches necessary for braiding. These artifacts, antler discs approximately 7.7 cm in diameter, were examined by Poul Nørlund in his report on the excavations at the Trelleborg fortress conducted between 1934 and 1942.

In his report (page 141), Nørlund identified these artifacts as spindle whorls. He noted that 39 spindle whorls were found during the fortress excavations, varying in material and size. According to Nørlund, the lighter the material, the larger the disc radius, which allowed the spindle to twirl effectively. The two discs in question were described as the largest in the collection.

One of the discs is described as carefully crafted, featuring a raised collar around the spindle hole and bands of plaiting on a shaded ground on its domed surface. The other disc is simply a thin circular piece with a small central hole.

This identification challenges the notion that these artifacts from Trelleborg were used in a manner consistent with the purported trollen wheel.

What is a spindle whorl?

A spindle whorl is a small, weighted object used in hand spinning fibers into thread or yarn. Made from materials such as clay, stone, bone, or wood, spindle whorls are disc-shaped with a central hole for the spindle shaft. The weight helps maintain the spindle’s momentum, ensuring smooth and consistent spinning.

These tools are well-represented in the archaeological record, with numerous extant finds that are well-documented and studied, providing insights into ancient textile production techniques.

About spindle whorls

The display at Slagelse Museum where one of the disks from Trelleborg is displayed

Photo by Russell Scott

Detail of the Trelleborg disk in Slagelse Museum

Photo by Russell Scott

The decorated disk from Trelleborg on display in the National Museum of Copenhagen

Photo by Jennifer Bray

The decorated disk from Trelleborg on display in the National Museum of Copenhagen

Photo by Jennifer BrayToday, one of the Trelleborg discs is housed in the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, while the other is in the Slagelse Museum in Denmark.

The simpler disk is displayed in the Slagelse Museum alongside a collection of other spindle whorls. In the same cabinet we can find also needles and other textile/sewing tools. Additionally, it’s positioned next to a display of comb-making items, possibly because comb makers usually worked with antler.

The decorated disc, now in Copenhagen, is also exhibited alongside spindle whorls, consistent with Nørlund’s identification.

Alternative theories

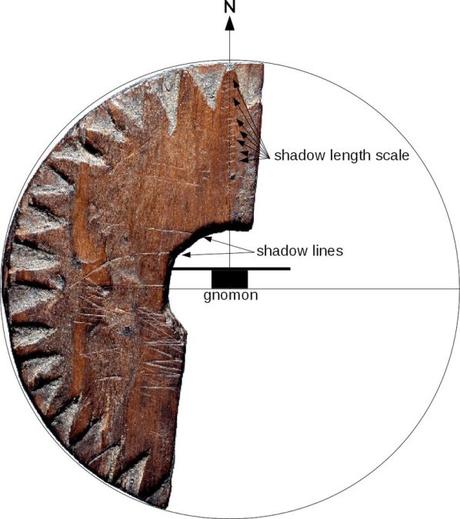

Additionally, part of a wooden disc found in the Benedictine convent at Uunartoq (Greenland) is often mentioned in relation to the supposed trollen wheels. This 7cm-diameter disc, however, is generally accepted to be a navigational aid. The notches present are only on the surface of the wood, further distinguishing it from the notched design of a trollen wheel. Also the shallow nature of those notches wouldn’t hold threads as securely as the deeper cuts used on

“trollen” disks, and moreover the carvings on this wooden disk would be more difficult to make than a simple cut through the edge.

About this artifact, researchers say it may have been used as a “twilight compass” by the Vikings on their long journey across the North Atlantic from Norway to Greenland. It originally had a central pin (a gnomon): when the shadow is aligned with the shadow lines, North is up. Incisions in that direction allow measuring the shadow length.

Extensive research by museums and archeology departments in the UK and Scandinavia have consistently failed to produce concrete evidence of trollen wheels. Sites often cited, such as Trelleborg, Birka and Heddeby, have not yielded any artifacts that match the description of these wheels.

Image of the original wooden disk fragment found in Uunartoq (Greenland)

Lennart Larsen, Danish National Museum, http://samlinger.natmus.dk/DO/10775, "Traedisk_Grønland", background of photograph removed and annotations added by Markus Nielbock, https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

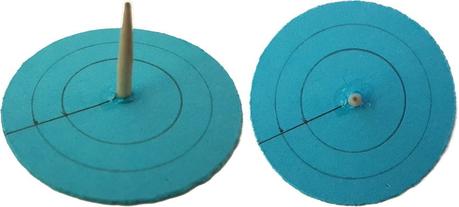

How the Greenland disk could have worked as a compass. Miniature shadow board, made of cardboard and a toothpick. Left: side view, right: top view

Markus Nielbock, "How the Vikings Navigated With the Sun", Max Planck Institute for Astronomy

Part of a wooden disc found in the Benedictine convent at Uunartoq (Greenland)

Another theory regarding the identification of trollen wheels is that they might not be braiding tools at all but rather box lids.

David Constantine in his study with Jennifer Bray and Shelagh Lewins, has suggested that the flat, uncarved disk resembled a vertebral bone disk (epiphysis) from a whale and could have been used as a lid for a container. During the Atlantic Iron Age, coastal communities often hollowed out whale vertebrae and other bones to make containers, and associated epiphyseal discs may have served as lids.

This practice continued into the Norse period, albeit less frequently. Examples of such perforated discs have been found at Iron Age and Norse sites including Clickhimin Broch and Jarlshof in Shetland, Pool, Gurness, and Quoygrew in Orkney, as well as other sites throughout Scotland. None of these discs exhibit wear patterns consistent with braid making or spinning, nor have notches similar to those found on supposed trollen wheels, supporting the theory that they might have been box lids rather than spindle whorls.

The lack of concrete historical evidence for trollen wheels is striking. In medieval texts and illustrations, there are numerous depictions and descriptions of textile tools and techniques. However, trollen wheels are conspicuously absent from these records.

Furthermore, the absence of notched disks in the archaeological record raises questions about the tool’s existence. Sites like Trelleborg, Birka, and Heddeby, which are often cited as sources for trollen wheels, have not produced any artifacts that fit the description of these tools. Despite extensive excavations and research, no notched disks suitable for trollen braiding have yet been found.

Proponents of the trollen wheel theory argue that the lack of evidence does not necessarily disprove its existence. They suggest that the materials used to make trollen wheels, such as wood or leather, might not have survived over the centuries. While this is a plausible argument, it does not account for the absence of any indirect evidence, such as depictions or mentions in medieval texts.

The research so far points to the likelihood that trollen wheels are a modern invention, inspired by historical techniques but not rooted in actual historical practice.

The relation between the trollen wheel and kumihimo

The resemblance between trollen braiding and kumihimo is particularly telling. Kumihimo has a well-documented history in Japan, with evidence of its use dating back to the Nara period (AD 710–784). The similarities in technique and tools suggest that trollen braiding might be an adaptation of kumihimo, rather than an independent Medieval European practice. When this adaptation came to be, is yet to be determined.

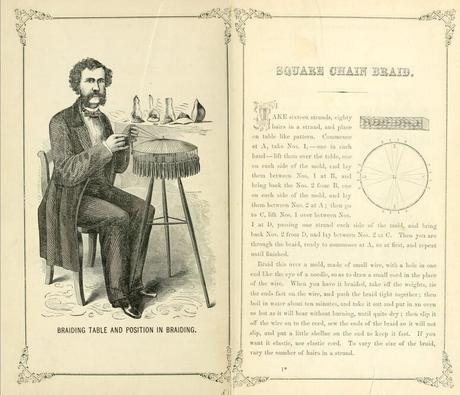

Someone says kumihimo became known in Europe no earlier than the 1970s, others say it was common in the Victoria age. There’s indeed a book from 1867 by Mark Campbell where we can find illustrations of a tool for braiding closely resembling a braiding disk. Well, even this evidence is inconclusive: those supposed disks are indeed tables, and without notches! An illustration of the author braiding shows him sitting at a table with a domed top, that reminds more of the bobbin lace technique.

This traditional Japanese braiding technique of kumihimo involves the use of tools such as the marudai or takadai, allowing for the creation of intricate and decorative braids used in armor, clothing and religious artifacts.

Besides the traditional tools, Makiko Tada designed a handheld disk for kumihimo braiding, that closely resembles the so-called trollen wheels.

Both the trollen braiding and the kumihimo technique share a similar process. The working threads are dangled from the edges of a notched disk with a hole in its center. The disk holds the threads in place.

Long threads may be wound onto bobbins or shuttles, while shorter threads can just be left hanging loose. The braid is built up through the center hole by moving the threads from one notch to another.

Conclusions: the role of the trollen wheel in reenactment

Despite efforts from many, the trollen wheel remains an enigmatic artifact, surrounded by ambiguity and speculation. Extensive research and examination of archaeological records fail to substantiate the existence of trollen wheels as Medieval textile tools. The antler discs from Trelleborg, identified by Poul Nørlund as spindle whorls, and other supposed artifacts do not fit the description necessary for trollen braiding.

In conclusion, while the trollen wheel captivates the imagination of reenactors and historians alike, the lack of concrete historical evidence strongly suggests that it may be a modern invention inspired by historical practices rather than a genuine medieval artifact. It’s likely that such a technique was adopted in Europe way after the end of the Middle Ages, when kumihimo became popular in Europe and the US, and from that on it spread, to reach in the end the living history community.

Despite the lack of historical evidence, the trollen wheel continues to be popular in reenactment communities for several reasons. Firstly, its ease of use makes it a convenient tool for creating braids, especially at events where participants can quickly make a simple wheel from materials like stiff leather. It’s an engaging activity for children and visitors, allowing them to participate in a hands-on crafting experience that can be paused and resumed easily.

Furthermore, the continued use of trollen wheels allows reenactors to engage in creative activities, offering a practical solution to avoid idle time in historical villages. Even though many authenticity enthusiasts recognize the trollen wheel as an anachronism, its practical benefits ensure its persistence.

Even though it’s less commonly used than the lucet or fingerlooping, I think we’re going to see trollen wheels again in living history events from time to time. It’s common in such events to see not-so-historical practices accepted as anachronisms: we live in a modern world where sometimes the most historical option is impractical, too expensive, or even impossible.

I believe that, if the reenactor really knows what they’re doing and why, and is willing to explain their choices to visitors and other reenactors, some of those anachronisms could indeed be a good thing. They could spark interest, start a conversation, and get people involved in understanding what historical research for reenactment is really like. For this, though, an explanation is paramount: use a trollen wheel, but be clear about what we know so far of its historicity.

It could be a fun tale to tell!

Resources

- Halldor Magnusson, “Trollen wheels” – an accepted anachronism, 2013

- Jennifer Bray, Shelagh Lewins, David Constantine, “Trollen” braid – the evidence

- Mulville, Jacqui, The role of Cetacea in prehistoric and historic Atlantic Scotland, International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 12, 2002, pp. 34 – 48. 10.1002/oa.611.

- Nielbock, Markus, How the Vikings Navigated With the Sun, 2017

- Nørlund, Poul, Trelleborg, Nordisce Fortidsminder, København I, 1948

by Rici86.